The two largest sports events of the year come with much fanfare: The NFL’s Super Bowl is famous for multi-million dollar advertisements and garish halftime shows, and the UEFA Champions League Final, which showcases the best soccer clubs from across Europe, garnered 360 million viewers last year to watch the winner be handed a 24-pound silver vase. But the two organizations that hide behind these displays couldn’t be more different. Underlying international soccer’s pomp and circumstance is a thorny nest of issues: tax hikes and exemptions, unchecked labor migration and unsustainable spending. The global marketplace for soccer stars, where teams fight each other tooth and nail in increasingly high-stakes bidding wars for the best players, leaves many teams in the red, season after season. These issues impact both on-field events and national economic equity in ways few soccer fans even realize. But on the American side of the pond, things look rosier. Here, the NFL has a monopoly on the football market and executives regularly rake in enormous tax-exempt salaries. Strangely, the NFL’s relative success can be attributed to many of the same labor and fiscal policies that, when present elsewhere in the world, red-blooded Americans love to hate: salary caps, regulations on labor mobility and redistribution of wealth. The economics of American football taste distinctly foreign.

Some European soccer teams are falling victim to rising income taxes and an unregulated labor market. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in France’s top soccer division, Ligue 1. Under President François Hollande, tax rates on incomes over €1 million jumped to 75 percent last April. The response from club owners and players was severe. The new tax hike applies to about 120 players — many of whom help give French soccer a face on the international market — and the league estimates that the tax could cost teams about €45 million. In protest, clubs and players threatened to strike. After finding insufficient public support, the strike was postponed, although the league’s office still struck a gloomy tone in a press statement: “With these crazy labor costs, France will lose its best players, our clubs will see their competitiveness in Europe decline and the government will lose its best taxpayers.”

This may be hyperbole on the part of the league, but France’s situation has begun to look frightful. French teams lost about €100 million in the 2012 season, representing an increase of about €15 million from the previous year’s deficit, which had climbed to about €120 million by 2010. In that season, 8 out of 20 Ligue 1 teams posted losses. Before the tax, French teams had been working to cure their financial ills without compromising the quality of soccer. When the tax arrived, clubs feared it would become much harder to continue to attract the best players.

The problem that French teams face — players leaving to find higher salaries — is born of international competition. In international soccer, teams can actually buy the rights to a player’s contract from their competitors in what is called the transfer market. This contrasts with other sports like basketball and American football, where players can move only if their contracts expire or if another team will trade players in exchange. The transfer market encourages player mobility for the same reason cash is superior to a barter system: Money facilitates deals, in this case between sports clubs. In the realm of professional soccer, the accessibility of other markets makes the labor supply much more elastic.

But more importantly, an international market allows players to command greater salaries from their teams, as illustrated in the case of oft-maligned Russian midfielder Andrei Arshavin. In 2009, Arshavin secured a transfer deal to Arsenal FC, a London-based club. But as the deal neared completion, England raised its tax rates on the wealthy in response to the recent global recession. Arshavin, who had been unaware that his tax rate would jump from 13 percent in Russia to roughly 50 percent in England, demanded that Arsenal almost double his agreed-upon salary. Though the club and player eventually came to an agreement, Arshavin is far from the only player who has reacted to changing fiscal policy.

This sort of open competition for wages has driven up player salaries dramatically, and some leagues have taken advantage of their countries’ low taxes to attract players. The most famous example of this is Spain’s “Beckham Law”: a flat tax for foreign residents that many believe precipitated David Beckham’s move from England to Spain. While millionaire Spaniards were made to pay a tax rate of about 50 percent, Beckham and other multimillionaires got away with a 24 percent flat rate on income earned in Spain, excluding money earned abroad. The trend in Spain favors rosters filled with the names of superstars from across the globe — Neymar da Silva Santos Jr., Cristiano Ronaldo and Karim Benzema, for example — at the expense of local players.

In 2010, a study called “Taxation and Migration of International Superstars” analyzed the effects of tax laws on the transfer market. The study was the first of its kind and showed that countries with lower tax rates are much more likely to attract top-level players. In fact, as rates go down, leagues see a significant displacement effect as foreign talent increasingly replaces domestic players. This was particularly true in the Spanish League, where the number of top-quality foreign players increased by almost 50 percent after the Beckham Law. As tax rates in Spain have dropped for soccer stars, the league has ascended in stature compared to its English and French counterparts.

However, it looks as if the tax holiday is over for many European soccer teams and celebrities. Recently, Lionel Messi, arguably international soccer’s greatest player, was charged by Spanish authorities with evading about €4.2 million in taxes. Some see Spain’s pursuit of Messi as a shot across the bow for Spanish clubs that collectively owe about €690 million in back taxes to the government. Much of this can probably be attributed to the deep financial woes facing Spain today. Even though soccer players usually retain their popularity in the face of such concerns, disenchantment with the status quo has put them at the center of rising public outrage. The trend holds across borders. English and Scottish authorities have also displayed impatience for domestic clubs’ tax evasion.

All of these problems combined — audits, rising player salaries and drops in profits for many teams — underline the main financial problem facing international soccer today: a lack of sustainability. In recent years, owners have invested billions to compensate for huge spending binges in the transfer market. The trend began with oil tycoon Roman Abramovich’s takeover of Chelsea FC. Since Abramovich became the team’s owner in 2003, Chelsea has posted losses of at least £50 million, or even double that, in every year but one. Meanwhile, Chelsea has become one of the best teams in the world. Following Abramovich’s lead, other wealthy investors have bought teams and spent huge sums hoping to ascend the ranks of European soccer. Although revenues have skyrocketed for most top clubs, many are experiencing huge losses. Even the teams who manage to turn a profit are often already mired in serious debt from previous losses.

The influence of big money has created a new mantra in soccer: lose money or lose games. Increasingly unsustainable spending threatens to concentrate talent in a few leagues. Teams like Chelsea are still reaping massive revenues; if their owners can hold out long enough, then they will eventually secure a stranglehold on the soccer market. What will emerge is a small group of elite teams from different leagues possessing almost hegemonic domination. The dwindling of talent in smaller local-pride teams is pernicious, and outsourcing can both destroy local morale and be culturally devastating.

UEFA, the European soccer association, is attempting to blunt these issues with a new initiative called “Financial Fair Play (FFP),” which would punish teams that operate with unsustainable finances. Teams in the red could face fines or even suspension from the transfer market. So far, implementation has been tepid at best. UEFA has identified 76 clubs, about a third of the European competition, to be investigated for breaching FFP rules, but the association has yet to level any serious punishments.

Perhaps FFP will bring spending back down to earth, but even so, the uneven concentration of talent might continue. Even in the German Bundesliga, which The New York Times called “the best-run league in the world,” a similar pattern has emerged. Though teams in Germany’s top division had overall profits of about €55 million in the 2013 season, FC Bayern Munich — the best-funded team in the league — claimed the championship title more than a month before the season’s end. The German league’s financial health, which commentators have attributed to reliable ticket sales and a particularly fruitful relationship with advertisers, isn’t enough to sustain competition.

The NFL, with a relatively spotless record, could teach international soccer teams a lesson. Unlike its counterparts in Europe, every NFL team has made a profit in the last few years. Moreover, the league has seen teams like the 2012 Indianapolis Colts quickly go from the bottom of the standings to Super Bowl champions. The most important difference is that the NFL is a monopoly and has no genuine competition from leagues with different operating guidelines — a luxury that European soccer leagues don’t share. And much of the NFL’s success can be attributed to a line of thinking more common in Europe than in the United States: the redistribution of wealth.

To ensure that no team has a significant economic advantage over the others, the NFL allocates its profits from the national office to individual teams much more equally than its European counterparts. Moreover, the league has a spending cap, meaning that all teams must keep their spending below a certain level. If the league’s left-leaning vibe wasn’t strong enough already, the worst-performing teams also get first access to the best rising college players through the draft. NFL teams are therefore virtually unable to concentrate talent, season after season, the way European teams do. Teams can still establish dynasties through good management, but there is much greater upward mobility for struggling franchises.

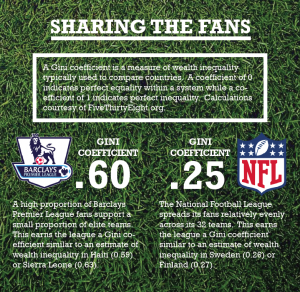

Recently, renowned statistician Nate Silver’s website FiveThirtyEight performed a study of fandom and financial inequality in sports leagues. Silver found that five teams in the English Premier League account for about 70 percent of media attention. Then Silver and co. calculated a Gini coefficient — the measure of wealth inequality in countries — for individual sports leagues. The NFL boasts a Gini coefficient of 0.25; in terms of equality, the NFL is the Finland of sports leagues, which is to say that it is extremely equal. On the other hand, the English Barclays Premier League’s Gini coefficient is about 0.60, comparable to the amount of inequality that exists in, say, Haiti or Sierra Leone.

It appears that, as the NFL benefits from a redistributive mindset, it simultaneously reaps benefits from america’ unwillingness to take a more European tax approach towards the wealthy.

This is certainly not to say that the NFL’s success has come entirely from its own policies — the league has also benefited from a few tax laws. While individual teams still pay taxes on salaries and other operating factors, the NFL central office, which distributes the money, has recently come under fire for its tax-exempt status. The NFL saves hundreds of millions every year because of its status as a trade union operator. For this reason, the NFL office can avoid paying taxes on Commissioner Roger Goodell’s $44 million salary and on other parts of its $9 billion operating budget. The NFL has responded to newfound questioning of its status with a significant lobbying effort against a tax reform proposal and other impending changes. It appears that, as the NFL benefits from a redistributive mindset, it simultaneously reaps benefits from America’s unwillingness to take a more European tax approach towards the wealthy.

So what can European leagues learn from the NFL? Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem possible for UEFA to solve most of the problems that its member leagues face. If leagues could lobby their sovereign governments to create tax loopholes in order to attract players, this might be beneficial in the short run. However, it would inevitably create a race towards the bottom in which countries would lower their tax rates to the point where millionaire players got off scot-free.

The NFL’s strength is its powerful central authority, and as long as there is an international, interconnected soccer market, UEFA needs to lay down the law. For this reason, the nascent FFP deal is a step in the right direction. As long as some teams can throw the money of their oil-magnate backers at the best players, poorer teams will struggle to compete. If UEFA could create an international system of redistribution so that leagues couldn’t benefit by stealing talent from their competitors, that too would stop the increased funneling of players towards the top teams in England, Spain and Germany.

What’s certain is that fair play is a necessity on the field as well as off of it — a line that could have been uttered by any European democratic socialist leader from the past half-century. Indeed, the irony of the situation is one that extends far beyond football. European leagues are in a position to look towards the United States for a successful model of centralized regulation and redistribution in a free market. Meanwhile, one can’t help but wonder if fans realize how much the NFL represents, in many ways, an antithesis and a response to much of American political thought.