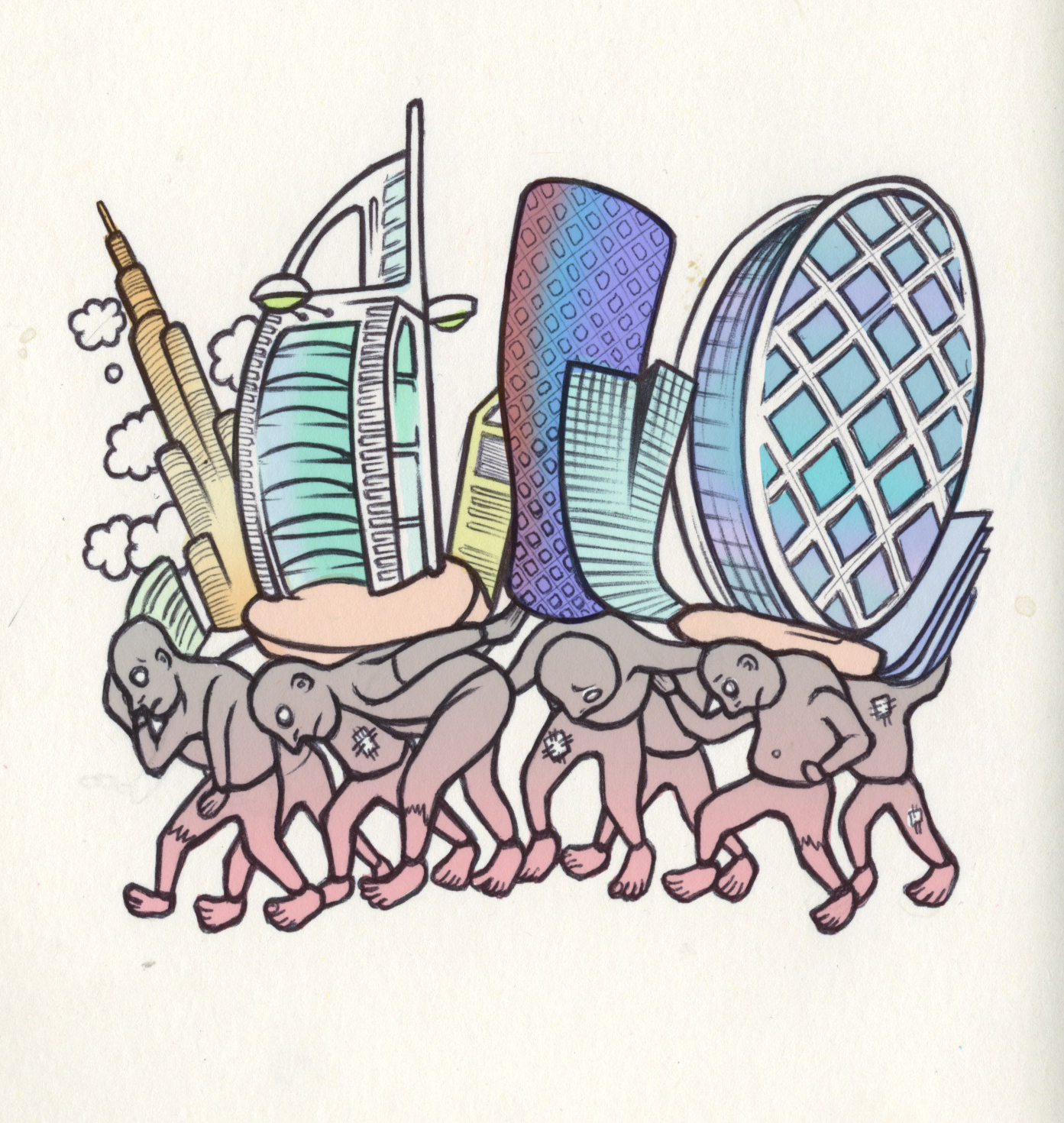

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is often hailed by the West as a model of stability and modernity in the otherwise tumultuous Middle East. Dubai and Abu Dhabi’s bustling skylines, emblazoned with glittering skyscrapers, have come to symbolize the miracle of the young state’s rise. Yet the foundations of these desert mega-structures are built upon the sweat and toil of millions of migrant workers trapped in a system of modern slavery. In 2013, the United Nations estimated that the UAE was home to the fifth-largest international migrant population in the world. Out of a population of 9.2 million, a staggering 80 percent, or 7.8 million, are migrant workers hailing primarily from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. But in the heedless pursuit of Western-style development, both the Emirates and the West have turned a blind eye to the suffering and abuse of this population as it is exploited in the process of creating modern oases of glass and steel.

Just off the coast of Abu Dhabi sits Saadiyat Island — a shimmering symbol of the UAE’s quest for modernity. The Guggenheim and the Louvre, literal repositories of Western civilization, are both constructing establishments there, as is another characteristically Western institution: New York University. With multiple billion-dollar projects in the works, the island will soon be a tourist and leisure destination, sporting the art, knowledge and opulence of the Western world. The Abu Dhabi-based Tourism Development and Investment Company (TDIC) has enthusiastically marketed the island, pitching a vision of a new Louvre “where rain of light patterns illuminate a micro-city of small galleries, lakes and landscaping.” But beneath the modern facade, the stories of those who labor for impossibly long hours under deplorable conditions to build these structures are all too easily forgotten.

In 2009, Human Rights Watch (HRW) investigated the construction sites of Saadiyat Island and published a damning report, finding that employers had committed a series of egregious human and labor rights violations. The report found that workers were paid significantly less than they were promised, that they were forced to toil through daily shifts of up to 12 hours and that their documents were seized upon arrival, making them powerless to leave. The workers were then denied access to judicial institutions and faced with swift deportation if they demanded change to their conditions or protested their maltreatment.

The government of the UAE was quick to respond to the report and has since initiated a vast number of reforms at the site. For example, the TDIC created the Saadiyat Accommodation Village to house all workers building Western cultural institutions. In the words of its developer, the village “provide[s] an internationally recognized, world-class standard of living.”

Nonetheless, a 2015 HRW report found the construction company still in violation of international law and continuing its abuse of workers. The rhetoric of reform, it seems, has proven hollow and catalyzed little change. Moreover, the sad truth is that, despite the continuation of deplorable conditions, the best place to be a construction worker in the UAE today is on Saadiyat Island. The rest of the country, largely out of the spotlight of the international media and hence exempt from the pressure for at least superficial improvements, has seen little to no reform.

Recruited from South Asia with promises of better lives for themselves and their families, the majority of migrant workers in the UAE find the promised “Gulf Dream” to be little more than a mirage. Workers’ journeys begin in their home countries, where the main channel of employment is often through agencies that place workers overseas. These agencies recruit men from low-income areas, advertising high salaries and opportunities in the Gulf that can help them support their families back home. It is in search of this dream that many men leave their homes, paying exorbitant sums, sometimes up to $4,100, to their agencies in exchange for being placed in a job. The payment of these fees is often funded by a whole family’s investment or by burdensome loans. As a result, even before they touch down at the UAE’s construction sites, many workers are laden with debt.

After arriving in the UAE, workers find themselves earning salaries far below what was promised and living in accommodations that frequently amount to little more than barracks, without even air conditioning to combat the sweltering desert heat. A significant proportion of the workers is housed in ominously designated “labor camps,” where often up to 12 men sleep in a room using a system of hot bedding, where, when one man leaves for his shift, another takes his place in the bed. In some of the smaller construction sites, particularly those outside of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, the accommodations are often makeshift and built by the workers out of construction site scrap materials. These unregulated sites often lack basic utilities like plumbing and electricity and, as a result, have poor sanitary conditions. For all this, the work itself is only for a pittance in wages.

Leaving is not an option. In addition to having their documents confiscated upon arrival, many workers are further bound to their employers through the kafala visa sponsorship system. Under this law, the sponsor controls the movement, working and living conditions of the sponsored worker. This patron-client relationship ensures that the foreign worker is almost completely dependent on his local sponsor.

Moreover, there exists no method of recourse, as workers are unable to access, or are actively excluded from, the justice system. Workers who have taken to other means of expressing discontent such as protests and strikes have been met with vicious backlash from authorities. In October 2013, 3,000 workers for BK Gulf on Saadiyat Island held a daylong strike against their employers in response to the withholding of their wages. The following day, the police rounded up hundreds of the men. Anamul al-Haque, who participated in the protests, claimed: “They pushed me. They slapped me. They demanded that I sign a form written in Arabic. ‘Sign and go to jail,’ they said.” Soon after, al-Haque was deported with the rest of the detained protesters. He has now joined the numerous men back in their home countries who are burdened with debt and who never even came close to attaining the Gulf Dream they had been promised. Cases like al-Haque’s demonstrate why, out of fear of deportation, most workers end up silently enduring their maltreatment. This ruthless response also highlights the absolute power that government authorities hold and the government’s loyalty to corporations over human rights.

Even when workers aren’t deported, the promise of making a decent living and sending money home is hardly ever realized. With no official minimum wage in the UAE — only a “suggested wage” — workers find themselves at the mercy of their employers, who have a right to dictate wages under the kafala system. Workers are therefore often paid far below the wage promised by the employment agencies that recruit them in their home countries. And that’s if the workers are paid at all. Wage theft is rampant in the UAE; recent strikes in Dubai, for example, protested the failure of Emaar Properties to pay its employees for their overtime work. Moreover, workers have no way to guarantee that they get the wages they are owed. Strikes are rarities in the UAE, where trade unions and collective action are illegal and the police respond swiftly to any indication of agitation.

The UAE’s record in the realm of international treaties and conventions is not a promising one for those waiting on reform. The nation is not a signatory to a majority of the international treaties and conventions that establish a framework for workers’ rights, including the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families. While the UAE is a signatory to both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and a number of International Labor Organization conventions, enforcement of these treaties is nearly nonexistent.

The institutions closest to these abuses have also failed to take action. The NYU campus construction site makes the token effort of asking workers for feedback on their working conditions — but on signs that only feature English, a language that very few workers speak or understand, let alone read or write. On the other hand, the Guggenheim Museum’s public relations team claims that the workers are only subcontractors, washing its hands of any responsibility for their living and working conditions. These examples indicate a disturbing trend: The West is simply shrugging off the blame for the human rights abuses of workers in the UAE. Yet Western institutions would be wise to demand better, since the Emirates’ development has, for far too long, been built on the backs of millions of migrant workers.

Art by Kwang Choi