In the preface of his 1945 novel Animal Farm, George Orwell remarked, “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” Seventy years later, if NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden’s exile in Russia is any indication, the world’s governments have yet to find a better way to shield themselves from such liberty. And now, a voice from the international community has entered the discussion. On September 8, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released a report to the UN General Assembly entitled “Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression.” The report, based on questionnaires filled out by 28 nations and 17 organizations, is the United Nations’s first explicit recognition of a whistleblower’s right to protection. The United Nations argues that such a right is a natural extension of the freedom to access information, as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, two longstanding doctrines of the United Nations. And although the report is anything but a binding mandate, it offers several suggestions that will undoubtedly have an effect on how different countries and the international community as a whole evaluate their treatment of whistleblowers.

Before discussing the specifics of the OHCHR’s report, let’s first consider why protection for whistleblowing exists in the first place. The power of whistleblowing is that it allows anyone within the public or private sector to expose institution-wide wrongdoings or corruption, thereby acting as a check against abuses of power. It is a democratic mechanism of the last resort, correcting and exposing issues that countless parties, like government regulators, have failed to find or let fester. The author of the OHCHR report, David Kaye, notes that there is no guarantee for the flow of information from the government to the public without whistleblowers: “Whenever the confidentiality of sources is compromised, whenever whistleblowers lack protection, we find that information simply doesn’t get to the public.” Whistleblowers do not only symbolize free speech in its most essential form. Even on an economic level, their revelations can be beneficial to society: they can expose inefficiency and gross misallocation of public resources. In the case of healthcare fraud enforcement, it has been found that “for every dollar the government spends to pursue whistleblower cases, more than $20 is recovered.” This societal benefit was the result of dangerous medical and pharmaceutical marketing practices being made visible by fraud investigations. These investigations were made possible by whistleblowers’ speaking out and testifying. Meanwhile, the personal risks taken by whistleblowers are increasingly real; a report by the US Merit Systems Protection Board found that federal whistleblowers were thirteen times more likely to be fired in 2010 than they were in 1992. As the OHCHR’s report notes, such reprisals have a chilling effect, allowing governments to “consolidate a culture of silence, secrecy, and fear within institutions and beyond, deterring future disclosure.”

The world faces two troubling trends that endanger both whistleblowing protection and the credibility of the UN’s suggestions. The first is the battle waged against whistleblowers by national governments across the globe; Julie Posetti of UNESCO found that over the past eight years, “nearly 70 percent of the 121 countries she reviewed had altered…policies on the protection of journalists and their sources.” Disturbingly, she concludes: “Most of those changes were negative.” One example is Australia’s new bill to revoke dual citizenship for the offense of releasing classified information; the bill is allegedly retaliation against whistleblowers accusing the Australian government of espionage in East Timor.

The second problem is the United Nation’s own treatment of whistleblowers. Kathryn Balkovac, a police trainer working for the United Nations in Bosnia, was fired for exposing a sex trafficking operation that involved members of the UN police. When asked about her rights as a whistleblower, she responded: “There were just so many levels and various steps and groups to work through, that it became almost impossible to report wrongdoing.” Senior aid worker David Kompass faced similar hurdles when he was suspended for revealing sexual abuse committed by French peacekeeping troops in the Central African Republic. Remarkably, even now, Kompass faces investigation from the OHCHR, the same organization that published the report with suggestions for the protection of people like him. Even for UN whistleblowers who don’t face punishment, the prospects of actually achieving positive change are dim. One of the United Nation’s most prominent whistleblowers, Aicha Elbasri, admits that peacekeeping missions like the one in Darfur suffer from “endemic underreporting and failure to investigate human rights abuses.” The United Nations and its organs will have to demonstrate concrete change and address their own hypocrisy if they want the report’s suggestions to be taken seriously by member states.

As far as the report itself is concerned, its eight suggestions are small steps in the right direction. Chief among them is the recognition that national laws need to be expanded to protect the confidentiality of all sources of information, not only journalists. In the words of the report, “Protection should be based on function, not title.” This guideline seems to echo the input of Julian Assange of WikiLeaks, who stated: “People no longer receive information only through ‘traditional’ media outlets.” The report also recommends expanding the protection of whistleblowers in all sectors of public life (including sensitive areas like national security) as long as positive intent is proven. It calls upon states to punish retaliation against whistleblowers. Finally, the report invites the United Nations to improve its own processes, noting that many of its whistleblowers lack the ability to appeal to a fair and balanced body within. This last point offers a glimpse of hope that the United Nations will rectify its own internal errors.

Still, the report has its limitations. While it aims to expand the rights and protection of legitimate whistleblowers, it does little to challenge current conceptions of what “legitimate” means. In short, it upholds the paradigm that threats to national interests warrant punishment. And conveniently enough, it defines national interest as “the rights and reputations of others, national security, public order, public health, or public morals” — categories so broad that they can be invoked in nearly any circumstance to justify retaliation against whistleblowers. While it’s impossible to deny that there are situations in which extreme national interests do warrant restrictions on whistleblowing, the OHCHR mentions that responses to these scenarios must be “proportional.” Unfortunately, under such a broad framework where national interests constitute a vast array of issues, and the positive intent needed for protection can be subjectively judged, reform will be needed to achieve proportional measures. The protections against liability that the OHCHR wants mean nothing in a world where it is impossible for whistleblowers to legitimately claim these protections in the first place.

The easy solution is to stop viewing whistleblowing solely in the context of its risks. As Julian Assange explains, the United Nations needs to explicitly acknowledge that, even if a revelation could potentially harm national interests, it should still be allowed “if public interest in knowing the information outweighs the harm from disclosure.” The report may well suggest promoting a culture of respect for the right to access information, but the OHCHR needs to do a better job hammering out what such a culture entails specifically.

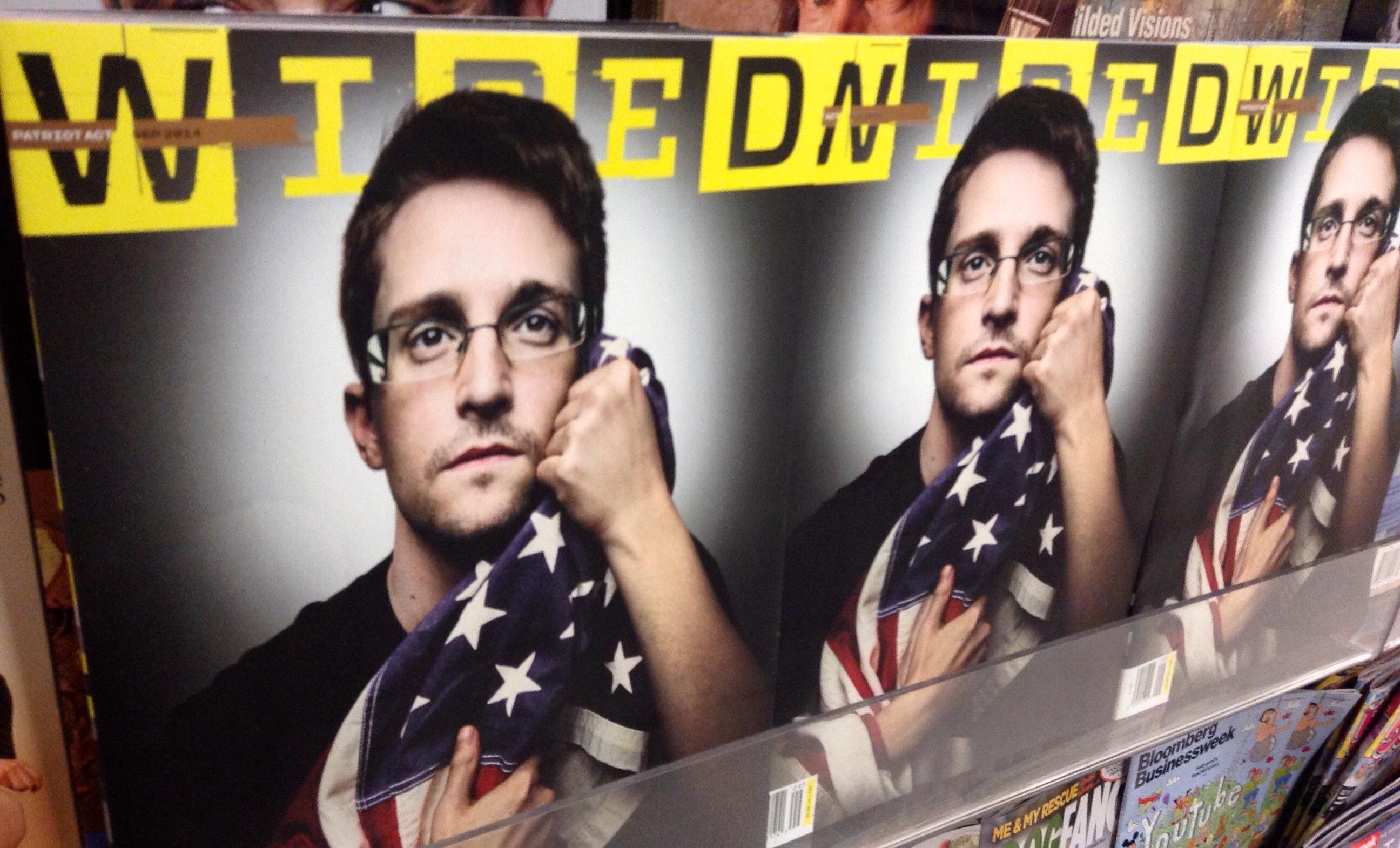

The United States is a good example of why the OHCHR report’s suggestions matter. Little in the Obama administration’s handling of Edward Snowden’s case suggests that in its early days it called whistleblowers “watchdogs of wrongdoing and partners in performance” who performed “acts of courage and patriotism.” Specifically, Snowden’s case shows how easy it is for a government to call into question a whistleblower’s positive intent. As Michael Glennon notes in an article in Just Security, the Obama administration has done so partly by arguing that the surveillance programs Snowden revealed had been deemed legal by the government and the courts alike, even though the whole point of Snowden’s actions was to subject the underlying laws to more adequate public deliberation.

The United States also argues in the questionnaire it submitted that it even extended protection in 2012 to whistleblowers that disclosed classified information. However, the United States only allows disclosure to be given to “inspectors generals and executive branch oversight entities,” not the public. Whistleblowers are no longer tools of last resort if they have to navigate through more levels of government investigation and approval. As US whistleblower attorney Jesselyn Radack concludes, the questionnaire “grossly overstates the protections for whistleblowers and journalists in the US.” The United Nation’s current suggestions can do little to rectify how the United States manipulates the whistleblower’s burden of proof and range of free expression.

The United States notes in its questionnaire that there’s a burden of proof behind restricting free expression so that it doesn’t “become a means to punish individuals who reveal information that poses more of a danger of embarrassing public officials or exposing government abuse”; ironically that’s the path the country has taken in its treatment of Snowden. In a video interview with Human Rights Watch in October, Edward Snowden noted: “A whistleblower has to almost become comfortable with the idea of becoming a martyr, because the probability of retaliation is so certain.” Any society or government that has let what once was a guarantee of democratic accountability morph into the ultimate act of self-sacrifice needs to pause for self-reflection. And hopefully, it is with stronger guidelines from the United Nations that hopes of reform can be achieved for international and national communities.