A devastating earthquake hit Nepal on April 25, 2015, killing more than 8,000 people and leaving millions homeless. Other nations quickly came to the rescue, sending supplies and search teams. The Himalayan nation was glad to accept any support it could get—or, more accurately, almost any. When Taiwan offered to send a rescue team, the Nepali government in Kathmandu declined, citing logistical reasons. Nepal also warned an Indian army rescue team not to encroach on China’s airspace. Many interpreted this behavior as an attempt to avoid angering China.

This unusual episode reflects a broader trend. Nepal is shifting geopolitical gears, pivoting away from its close ally, India, and drawing closer to its northern neighbor China. This shift is likely to accelerate: In late 2017, Nepali voters handed victory to a fledgling alliance of two far-left, China-friendly parties. The two communist groups won a majority at all levels of government. The coalition which took over in February is expected to further steer the country toward China at the expense of Nepal’s traditionally close historical, cultural, and religious ties with India. The move may increase Nepal’s role as a pawn in the Sino-Indian geopolitical rivalry, and the country should take care to strike a balance in its closeness with both countries.

Nepal’s 2017 election took place without any major disruptions, despite occasional violent skirmishes and attacks. The country’s path to democracy, however, has been rocky. Following pro-democracy protests against the country’s monarchy by the center-left Nepali Congress (NC) Party and leftist groups, a democratic constitution was adopted in 1990. However, Maoist groups, calling for the complete abolition of the monarchy, began a decade-long insurgency in the 1990s, leaving more than 18,000 dead. In 2008, two years after a peace agreement was reached, the country finally abolished its monarchy in favor of a republic. While large-scale violence has since subsided, the country has remained politically unstable, having been led by 10 prime ministers in as many years.

Wedged between two economic giants, Nepal has been asymmetrically dependent on India for much of its modern history. Its only reliable outlet to the sea is accessible through Calcutta, India—more than 1100 km away—and Nepal relies on its southern neighbor for essential commodities, such as heating fuel, petrol, paper, rice, and many other manufactured items. In 2015, India accounted for more than half of Nepal’s imports and almost two-thirds of its exports.

Although mutually beneficial in some regards, the Nepalese-Indian relationship is far from balanced. For one, some bilateral agreements, such as treaties to manage irrigation, have noticeably more benefits for India. Moreover, Nepal’s reliance on Indian imports means New Delhi can put the country in an economic stranglehold at any time. This power dynamic became painfully clear in March 1989, when India closed most of its border crossings with Nepal for over a year, causing fuel shortages and sparking protests and riots. The blockade was widely understood as an attempt to discipline Kathmandu for an arms deal with China, which signaled closer ties with Beijing. For India, Nepal has long served as a buffer against its archrival China, with whom it is competing for regional dominance. For this reason, India wants a friendly regime in Kathmandu, and the 1989 episode was one of the first indications that India was willing to use its economic leverage to make sure the Nepali government stayed in line.

Indian skittishness notwithstanding, China has gradually expanded its involvement in the Himalayan nation over the past decade. In 2014, China overtook India as the largest source of Nepali foreign direct investment, and Nepal is an increasingly popular destination for Chinese tourists. The two countries have signed agreements on transit trade, investment in solar energy, connectivity, and the export of Nepali petroleum and oil products. Last year, the two countries held their first-ever joint military exercise, and Nepali security forces have even been accused of systematically repressing Tibetan refugees to prevent anti-China activism. China, of course, is not just building these ties out of goodwill: Beijing’s overtures are part of a larger attempt to encroach on India’s South Asian dominance.

Following the 2015 earthquake, China and India seemed to be competing to deliver aid to Nepal, sending disaster response forces, medical teams, and rescue equipment. However, Nepali public opinion did not always respond kindly to what was perceived as overbearing Indian media focused on glorifying their country’s rescue mission. In fact, the spread of the hashtag #GoHomeIndianMedia actually forced the Nepali government to reiterate its gratitude to India.

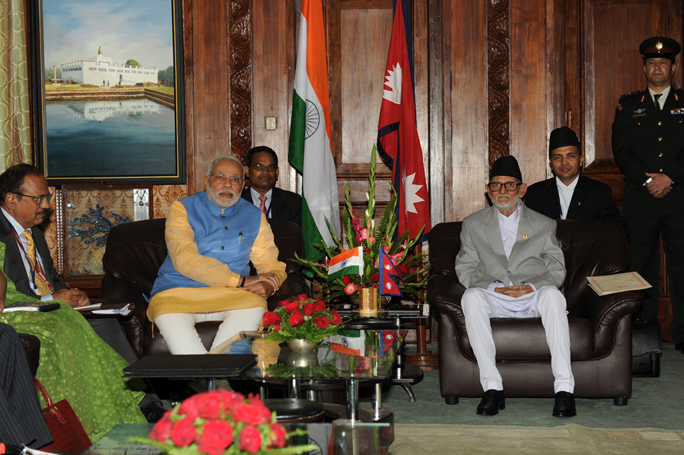

Yet tensions between Kathmandu and New Delhi soon flared up again. In September 2015, a few months after the earthquake, Nepal ratified a new constitution after almost a decade of political wrangling. While the document was meant to consolidate Nepal’s status as a democracy and contained a number of highly progressive clauses, it drew the ire of minority groups like the Madhesi, an ethnic group in southern Nepal with close ties to India. The Madhesi argued that provincial boundaries drawn under the new constitution would undermine their political unity and representation. Since the Madhesi were also a critical source of votes for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in north-eastern India, Modi’s government rejected the new Nepalese constitution as an undemocratic instrument to disenfranchise minority groups. India’s concerns that the new constitution would impact its domestic politics and destabilize its northern neighbor culminated in an unofficial six-month blockade of oil tankers and consumer goods en route to Kathmandu. As was the case in 1989, the 2015 blockade led to serious fuel shortages in Nepal.

Nepal’s prime minister at the time, K.P. Sharma Oli, vocally criticized the blockade and made clear his ambitions to wean Nepal off its economic dependence on India through closer cooperation with China. Oli even attributed the collapse of his government in 2016 to Indian meddling. Now, Oli leads the newly elected far-left Left Alliance government and has shown no signs of changing course regarding India. The Left Alliance has blasted what it sees as India’s “semi-colonial” relationship with Nepal, and Oli used symbolic attacks against India and made multiple trips to China throughout the election. He even warned that the India-Nepal Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1950, which forms the basis of the two countries’ close political and economic ties, would be discontinued under the new government.

Oli’s government is likely to prioritize trade relations between Nepal and China. For instance, the new government plans to support a large-scale hydropower project awarded to a Chinese contractor—a deal from which the previous government had pulled away, likely under pressure from India. In January 2018, Nepal Telecom and China Telecom Global launched a collaboration to offer Internet to Nepali citizens, effectively ending Nepal’s decade-long dependency on Indian telecom services. The new government also plans to continue cooperation with China on its “One Belt, One Road” initiative, Beijing’s plan to build a network of sea and land trade routes across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Nepal hopes that involvement in the plan would open up new gateways for international trade, create employment, and offer opportunities to increase tourism.

There remains a possibility that, under Nepal’s hard-won new constitutional framework, Oli’s government is here to stay, and that it will be able to focus more on development than previous administrations. Considering this along with the new government’s Beijing-friendly stance, India can no longer afford to take for granted its historical ties to, and influence over, Nepal. This is especially true because China has positioned itself to take advantage of Nepalese frustration with Indian influence.

However, the Left Alliance’s strategy of alignment with Beijing has its limits. Some of the country’s links to India are deeply ingrained in its history and culture, making them very difficult, if not impossible, to dissolve. India flanks Nepal on three sides. The snowy, mountainous Himalayan border with China lacks infrastructure and is not a convenient route for trade. No degree of political and economic maneuvering can compete with these hard geographical facts anytime soon.

Moreover, Oli understands that, to date, no government in Nepal has managed to sustain a hostile foreign policy toward New Delhi—in 2009, then-Prime Minister Prachanda lost his position in large part by crossing India. Some commentators also doubt how committed Oli will remain to his anti-India stance once in office, arguing that it was driven more by electoral politics than ideology. Indeed, even the NC, historically well-inclined towards India, has struck more anti-Indian tones in recent years, perhaps in an attempt to capture more votes.

Given this history, a complete pivot to China may be economically expedient for Nepal, but politically unwise. Nepal cannot afford to choose one of its neighboring nations at the expense of its relationship with the other. Instead, it should leverage both nations’ interest in the country to attract investment and increase stability. Nepal has the unique opportunity to present itself as a valuable transit country between China and India, a multicultural hub for Indian and Chinese nationals, and a part of the Chinese “One Belt, One Road” initiative. By striking a balance in its relationships with China and India, Nepal may be able to sustain a relationship with the former, maintain its deep cultural connection with the latter, and gain enough independence to mitigate economic pressure from both. Photo