First Evergrande, and now Country Garden: Massive Chinese developers are beginning to buckle under the pressure of 7 billion square feet of unsold homes. In the last 40 years, the country’s robust real estate market has been lauded for propelling China and its people into economic superstardom. It was a veritable machine for reintroducing the nation to market economics, even in a heavily controlled manner. In the wake of the pandemic, however, a marked fall in consumer demand for real estate strained the already struggling sector. The overabundance of housing has created the conditions for a bubble, where dwindling demand simply cannot meet the vast supply.

China’s current predicament has ominous similarities to the 2008 trans-Atlantic housing bubble, which wreaked havoc on the global economy. If China’s housing bubble is to well and truly pop, the country may be facing a massive domestic debt crisis. However, owing to China’s uniquely unilateral system of fiscal management, this crisis is unlikely to reach the international impact of the 2008 recession.

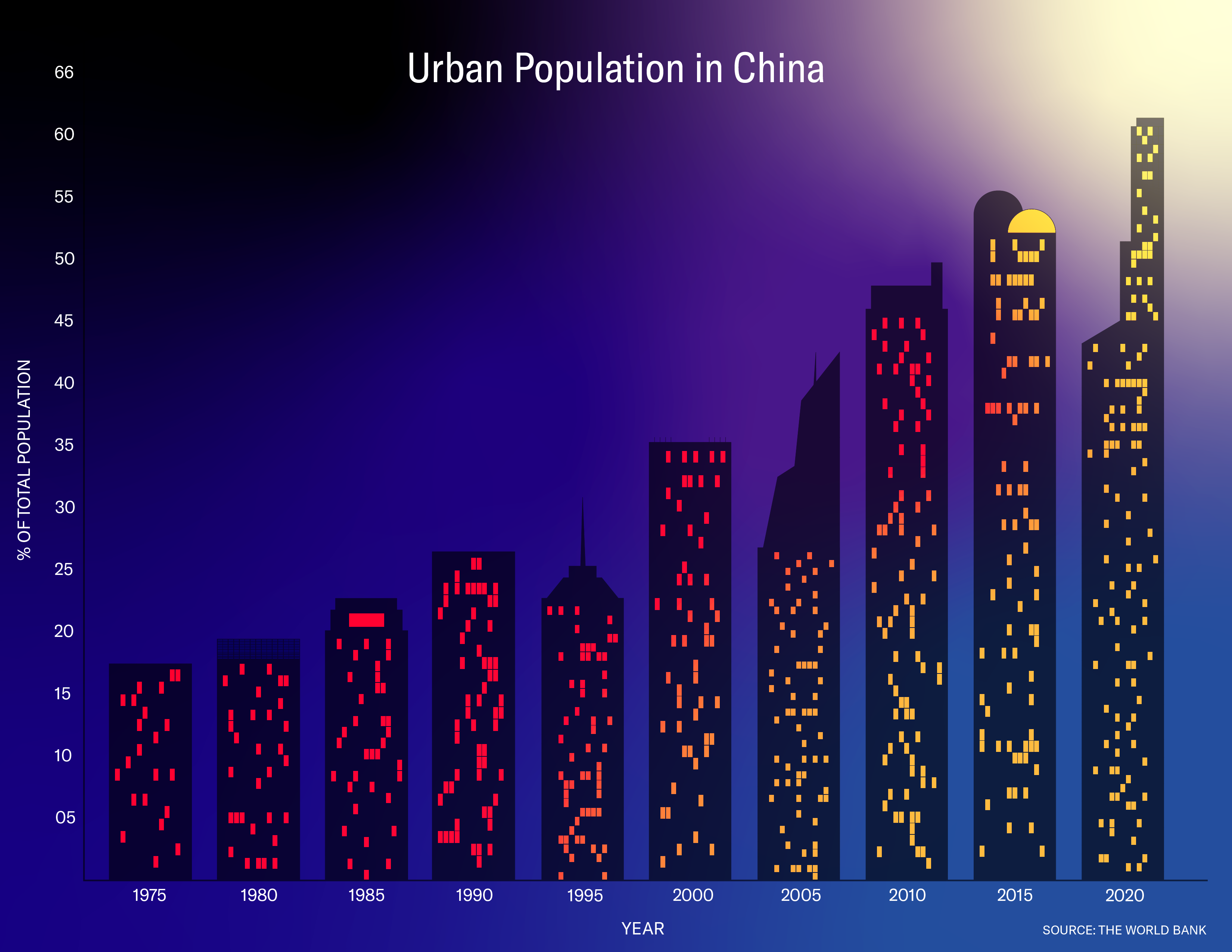

China’s robust urban real estate market facilitated the explosion of its cities at the turn of the 21st century. In the years of reform and opening following Mao Zedong’s regime, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership adopted urbanization as a favorite strategy for economic growth. Under Deng Xiaoping in the 1990s, the Chinese government began leasing land to developers en masse and subsidizing the construction of high-density housing, essentially pushing its citizenry toward urban living. This acted parallel to the hukou system, which restricted citizens to one permanent place of residence, categorically defined as either rural or urban—a system leveraged to incentivize Chinese citizens to move to cities and stay there. From 1980 to 2020, the share of China’s population that lived in cities grew from 19 percent to 64 percent. Investment in construction provided millions of jobs to this nascent urban population, becoming a critical dimension of the state’s economy.

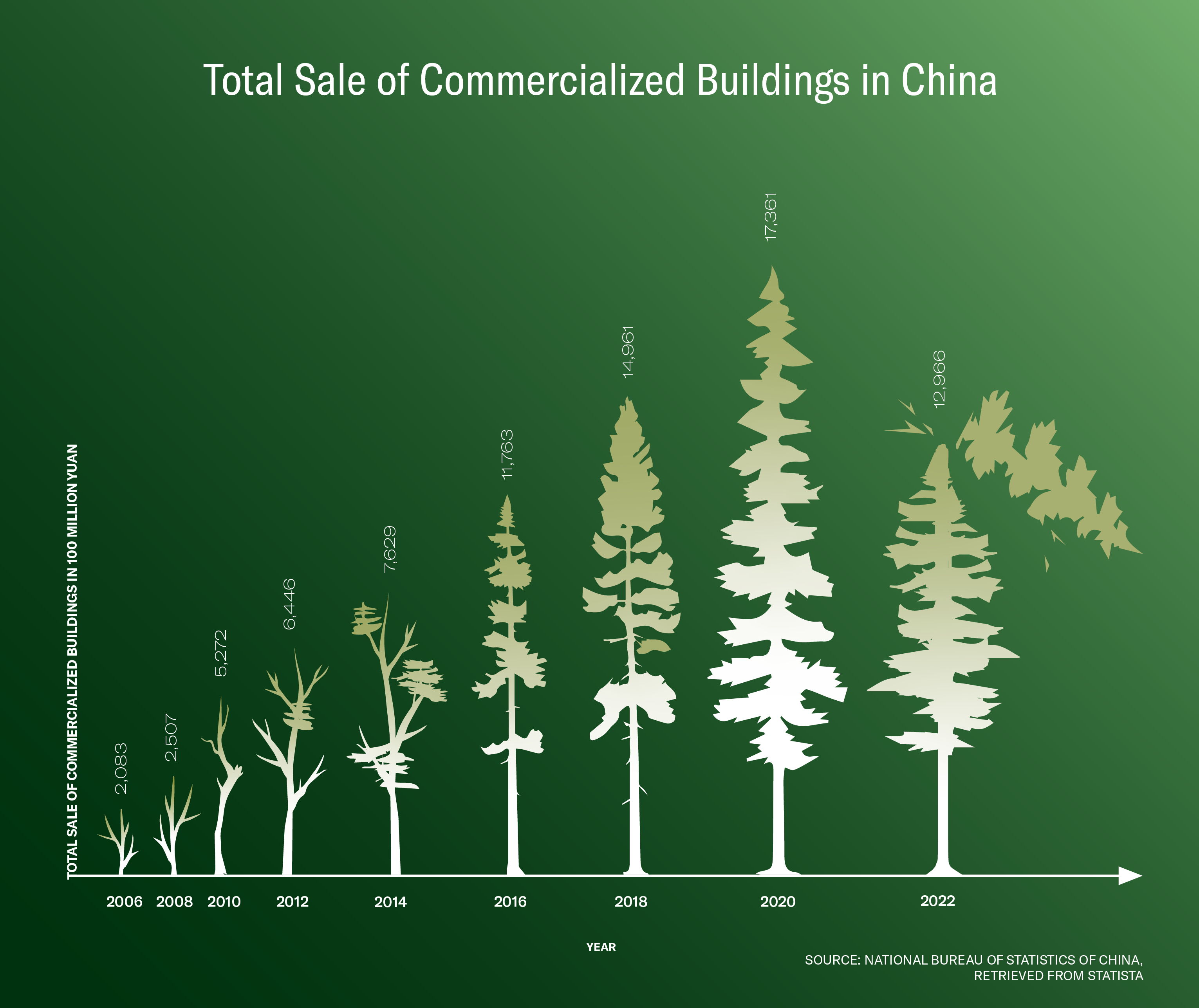

By all accounts, the economic strategy worked. China has become the second largest economy in the world, with the country’s real estate sector accounting for 30 percent of its GDP. However, the lifespan of this strategy has been finite, as declining population growth coupled with a downturn in consumer spending in the wake of the pandemic spelled an end to the decades-long boom. The dwindling demand for housing simply cannot meet the now-exorbitant supply, and major development companies, notably Evergrande, have been unable to make their debt payments.

How severe is this problem really? The 2008 financial crisis offers a fresh and potent frame of reference. China’s current situation mirrors the early-2000s United States in some striking ways. Like China, the United States also saw a speculative magnitude of supply, with major banks and financial institutions wielding instruments like subprime lending to capitalize on rising prices. Moreover, large debts were held by shadow banks: financial institutions lending in the fashion of banks but without the legislative guardrails that guarantee the security of their investments. As the originators of subprime lending, shadow banks played an important role in creating the circumstances for the 2008 crisis.

Today, shadow banking accounts for a large portion of China’s financial activity, and the mass sale of land by municipal governments to developers has entrenched real estate in cycles of speculation that have now soured. Reports on the troubles of big-name Chinese developers like Evergrande and Country Garden are troublingly similar to those of US investment firms like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns. Where major commercial banks in the United States were considered “too big to fail,” in China, government-owned financial institutions, both within the traditional banking sector and outside of it, are guaranteed by the state.

However, the divide in political economies between the two nations is a salient factor in distinguishing China’s current situation from the 2008 crisis. In the United States, responding to the crisis involved complex conversations between private banks, politicians marred by growing partisanship, and a vocal constituency entitled to governmental representation and property rights. Furthermore, investment through these private banks had a distinctly international tilt, with many North Atlantic countries taking part in the housing boom. Thus, as conditions worsened and economic malaise set in, myriad competing interests made a swift and effective response difficult to achieve.

In this way, the Chinese situation is fundamentally different. Though China has some of the trappings of a market economy, the state is omnipresent—it controls the largest banks, financial institutions, and land. While Americans placed undue trust in the all-encompassing scope of the private banking sector, Chinese faith is backed directly by the legislative body that controls how much and in what fashion lending can be done. This structural organization makes clear that the onus of wrangling an outsized shadow banking sector and recapitalizing major banks lies solely with the state.

Chinese financial leadership has proven its chops in the past. During the 1990s Asian financial crisis, the country maneuvered through regional instability with capital controls on foreign investment and widespread reform of the state-owned enterprise system. In 2008, it again stabilized the global market with a staggering stimulus package, which propelled it as one of the first to emerge from the global recession. There have also been significant pushes to reduce the power of shadow banks, including a legislative move in 2016 that limited the scope of shadow banking institutions and redistributed public debt back to state-owned banks. Such decisive macroeconomic action was made possible in no small part by the ability of the Chinese government to act unilaterally—rather than working through democratic channels to implement policy, it enacts change through state-controlled financial institutions as it sees fit.

The legacy of these fiscal responses protects the global market from exposure to China’s teetering real estate market. Monetary policy centered around protectionism of core domestic interests, namely real estate and finance, has made foreign direct investment in the industries exceptionally limited. As such, recent simulations have argued that a hard-landing outcome for China in the face of its current situation would not spell disaster for countries like the United States. Investment and consumer banks across the globe are decidedly removed from Chinese real estate, meaning a crash in the market would be unlikely to result in a complete collapse of these institutions. It was the globally interwoven fabric of financial institutions tied up in American real estate that prompted a worldwide collapse. Ultimately, China’s debt is held and backed by itself. Ricochet effects are certainly possible, with trading partners like Japan, Korea, and Germany likely to experience a hit, but the spillover from these countries to the United States is predicted to be small.

Chinese leadership holds its fate in its own hands. Though its heavy investment in real estate and development was an economic engine for decades, that era may be drawing to a close. Beijing must continue to rethink its negotiation with shadow banks, utilizing its leverage as a unilateral decision-making body in moderating fiscal policy to assume debt where needed and transition its economy away from real estate. It is no small task, to be sure, and the efficacy of the government’s response could determine the long-term legitimacy of the CCP. But it has worked its way through crises before, and the tools it needs lie before it.