In 2011, researchers at Vanderbilt University wanted to test the effect of name recognition on candidate support in the Nashville Metropolitan Council race. They put up yard signs in support of Ben Griffin near a local elementary school, then sent a survey to parents asking for their top three candidates out of the seven in the race. Significantly, nearly a quarter of respondents included Ben Griffin in their top three, compared to 14 percent of a control group that did not see the signs.

Even more significantly, Ben Griffin did not exist.

Low-information voting is among the simplest reasons why elections suck. Low voter turnout, lack of demographic diversity among candidates, and voter bias make elections—especially local ones—ineffective at achieving democratic representation. Voter suppression, gerrymandering, lobbying, and campaign finance corruption only make matters worse. Fortunately, there is an innovative solution for local government: sortition. Replacing elected officials with randomly selected citizens may sound radical given the common assumption that elections are essential to the democratic process. However, contemporary experiments with sortition around the world suggest that it is both efficient and effective.

As demonstrated by the Ben Griffin experiment, voters are rationally ignorant. In most elections, they make decisions based on very limited information, like having seen a candidate’s name on a piece of cardboard. A swath of literature indicates that other superficial factors, like having your name listed first on the ballot and being physically taller and conventionally attractive, all yield significant, measurable advantages. All elections are, on some level, glorified beauty pageants.

Additionally, in the United States, the nature of political campaigns filters out would-be leaders who find the process prohibitively expensive or draining. Local politicians are disproportionately white and wealthy, and women remain underrepresented at all levels of politics. According to a 2012 American University study, this is not because they are less electable, but because they perceive themselves as less “competitive” and “entrepreneurial” than men do and choose not to run. Women also tend to react more negatively to certain aspects of campaigning, namely fundraising, dealing with the press, and loss of privacy.

Elected officials who do not serve their constituents’ interests are rarely voted out. In fact, a study found that in the period 1974-2004, 95 percent of incumbents in the House of Representatives won reelection despite a trend of extremist and polarized voting records. The authors of this study explain that “the fact that voters only infrequently penalize [extremist] behavior reflects not approval, but rather the limited capacity of voters to discern extreme policy agendas for what they are.” Corrupt officials are regularly reelected, whether that be because of low information, ideological alignment, or simply the belief that all politicians are corrupt. Low voter turnout is also evidence of disengagement. Nationally, voter turnout for federal elections has never topped 67 percent, and average voter turnout for local elections lies at a paltry 27 percent.

Many voices, from Yale University professor of government Alexandra Cirone to climate activist group Extinction Rebellion, believe the solution lies in democracy’s own roots. Instead of electing career politicians, what if ordinary citizens were chosen by lottery to make policies, as they were in ancient Athens?

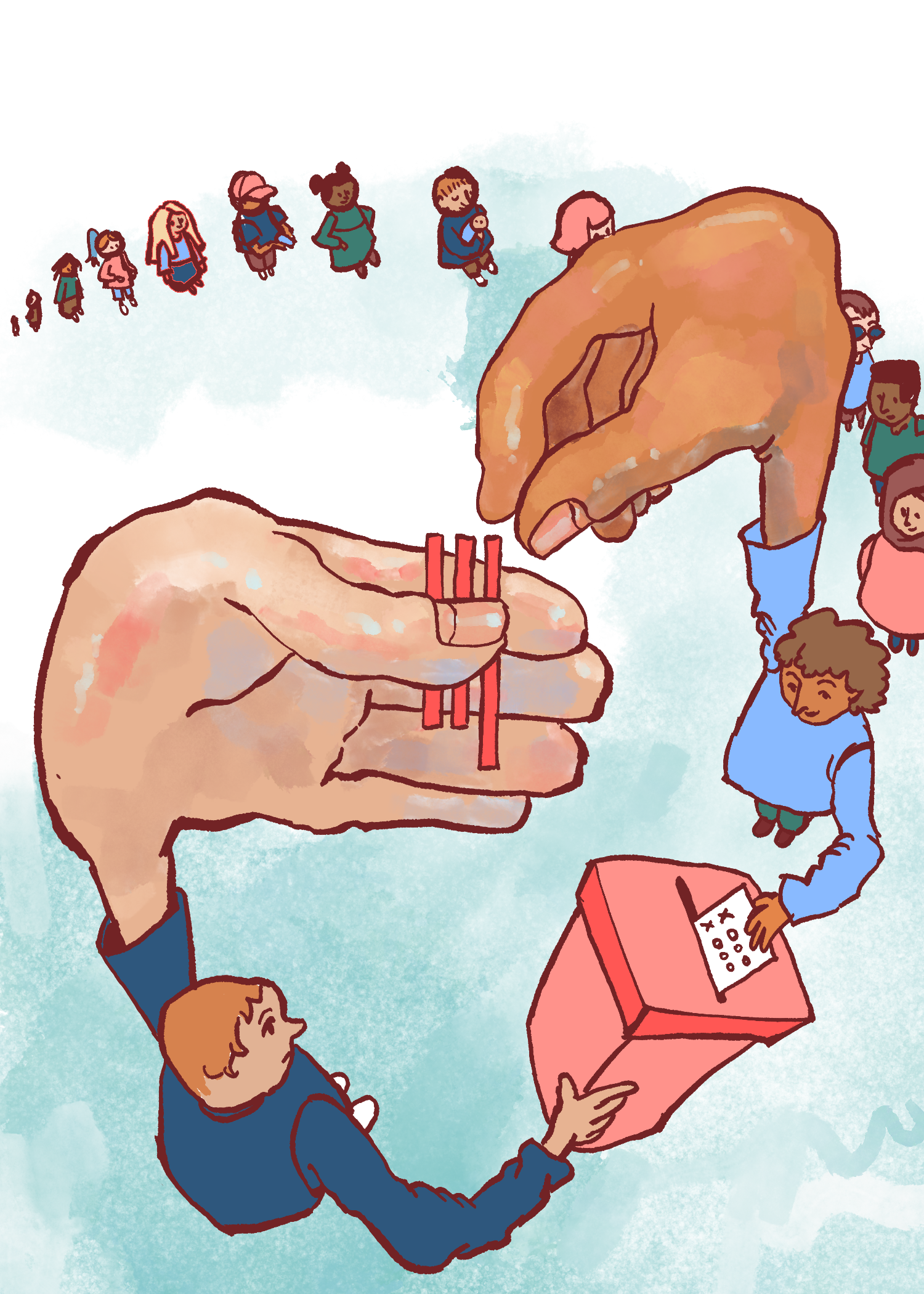

Today, sortition might resemble an intensive form of jury duty. Thirty or so registered voters would be selected randomly, perhaps stratified according to relevant demographic criteria such as race, gender, and socioeconomic status. They would then serve as government officials for a short term—perhaps six months. In this role, officials would be responsible for drafting and voting on government policies: They would receive public comments and consult with relevant experts before coming to decisions. Local elections would not necessarily be done away with completely—for example, a city council might be selected randomly, but the mayor would remain an elected official. As with jury duty, employers would be required to give time off. Selected officials would also be paid and provided with childcare, housing, and other necessities.

Sortition has many advantages over elections. This system circumvents corruption and corporate capture because there is no campaign financing and no fear of losing re-election. In the absence of a lengthy campaign period, leaders would spend more time working and less time kissing babies. Because they would be selected randomly, local officials would no longer be disproportionately wealthy, white, and male but rather a diverse representation of their community. Citizens may find leaders who do not fit the traditional “Type A” career politician mold more approachable, trustworthy, and empathetic.

Without entrenched loyalties and partisan agendas, local assemblies would most likely come to a consensus faster—disagreements would be real instead of manufactured. Sortition does not directly address low-information voting or low voter turnout. Instead, it cultivates a sense of civic responsibility and patriotism by returning power to the people. A system of sortition understands that citizens are normally rationally ignorant, but trusts that when responsibility is handed to them, they will rise to the occasion.

Over the past decade, many countries have held citizens’ assemblies in which citizens are randomly selected to deliberate and make policy recommendations to legislators. Hundreds of these assemblies have been held around the world with great success. An Irish citizens’ assembly’s proposal to legalize abortion was sent to a national referendum; in France, an assembly submitted recommendations on combating climate change to the incumbent government. Citizens’ assemblies can be effective pilot programs, proving to the public that sortition works. Ideally, they will become regularized and eventually hold direct legislative power in local government.

If I’ve convinced you that lotteries are preferable to elections, and you’re wondering what to do about it, we can start right here at Brown. Our student government election process has room for improvement. I don’t know about you, but I only voted for the people who asked me to or who had cute posters, neither of which seem like a good indication of the best future leader. Voter turnout in the class of 2026 first-year elections was only 33.5 percent. And, as we saw with the recent Undergraduate Finance Board budget surplus fiasco, who our student government representatives are matters. Let’s make it an opt-in lottery at Brown—and then take it to the rest of the country.