As sea levels continue to rise, floods threaten to destroy the populations of coastal cities. By the end of this century, metropolises such as Lagos, Bangkok, and New Orleans could be underwater. Venice put up sea walls in 2022, the Coachella Valley is relocating groundwater to prevent sinking, and houses on stilts have become a staple to accommodate high water levels. However, these are not long-term measures. Urban administrations must choose between altering the coastal landscape and the relocation of populations further inland.

Coastal Florida and Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, are two such urban administrations that proposed very different responses to the existential threat of catastrophic flooding. Responding to pressure from tourist-subsidized real estate companies, Coastal Florida has opted for a kind of urban renewal aimed at preserving existing housing. By contrast, Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, has devised a master plan to rebuild Jakarta on another island. Both methods could be successful, but they could also exacerbate class differences, widening social and economic gaps with long-term consequences for the inhabitants. Instead, a more flexible urban form needs to be developed to withstand climate change.

Initially, Indonesia’s plans were to rebuild Jakarta in its original location, implementing sea fortifications and building flood-resistant housing. However, Dutch canal construction in Jakarta separated the land from the rivers that brought nutrients to the coastline, ultimately worsening soil erosion. With water quality declining and parts of the city already underwater, Joko Widodo took office and proposed to build a new capital, called Nusantra, in inland Borneo.

The president provides an optimistic vision: “This is not physically moving the buildings. We want a new work ethic, new mind-set, new green economy.” This provides a great incentive for those with the means to move to Nusantara—and the relocation will be subsidized in phases, beginning with civil servants this year. However, unskilled laborers of lower classes—those who suffer most from the flooding—will be last to move. Those who remain in Jakarta will see a socioeconomic demographic shift: As capital and opportunities flow to Nusantara, chances are that the former capital will become run down entirely. That is, if the new construction plan is successful. Nusantara is currently undergoing construction, but Widodo’s administration does not have much time to finish the project: His term ends at the end of this year, and his opposition does not support the relocation of the capital. Widodo started the project when his approval ratings were at an all-time high—76 percent. Woods have been cleared, and the foundations of buildings have already been set, but Nusantra’s future remains uncertain.

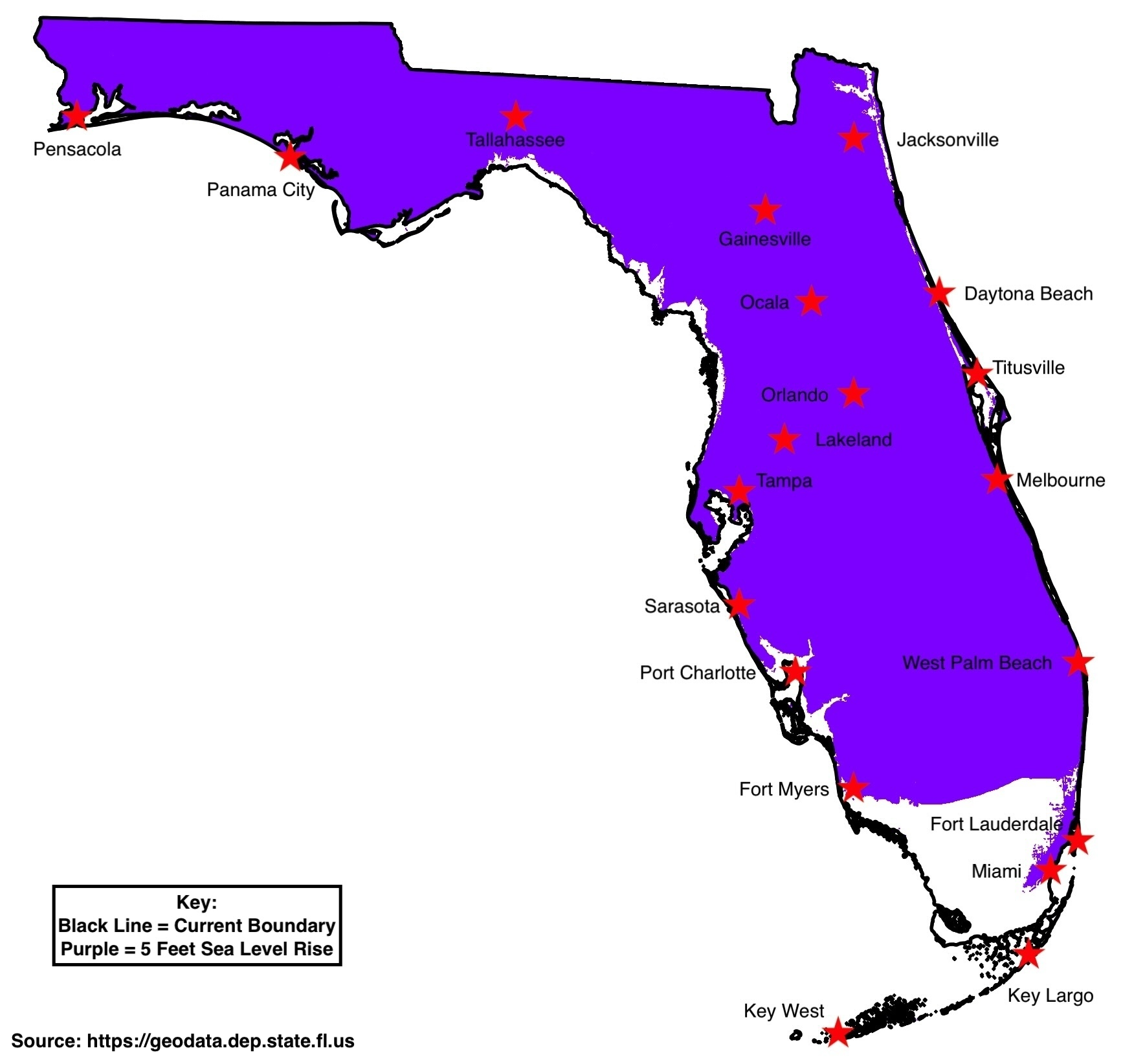

In some areas around the globe, populations—mainly wealthy ones—are choosing to stay behind. The Helmholtz Institute of Climate Service Science predicts that investment in adaptation will be much higher than investment in relocation as climate change progresses, citing high-income density in coastal areas as a driving factor. When led by corporations, sustainable development is directed toward places with money, not people, ultimately restricting the mobility of those who permanently inhabit these places. A Cornell and Florida State University study found that nearly a million coastal properties in the state are projected to go underwater by the end of the century—a combined tax loss of $619 billion to Florida municipalities. 33% of Miami Beach’s real estate landscape is composed of vacation homes. To combat the rising sea levels, Florida’s coastal counties require builders to construct taller buildings in high flood areas. At the same time, insurance companies are increasing flood insurance rates (see figure). Taxpayer money is stuck in the beach house repair economy, while hurricanes and floods continue to hound Florida’s population—827,000 Floridians were displaced last year. Considering that lower-income communities are often pushed to flood-prone areas, the aid seems misdirected.

Alternatives to traumatic relocation and inequitable adaptation subsidies have benefited coastal populations threatened by flooding. For example, the city of Curitiba in southern Brazil has built parks on the banks of the Iguaçu River so that they turn into public lakes when the river floods, allowing groundwater to drain without oversaturating paved streets. A healthy middle ground between clinging to coastal assets and relocating large populations lies in creating flexible, non-linear cities. This urban form has evolved around flooding river valleys, with silt providing fertile soil. Instead of cutting down inland forests to expand a city’s hinterland (which would further contribute to the rising sea level), we could view the expanding sea as a resource, tapping into the growing industries of algae and fish farming.

We could go even further into rethinking the house as mobile, the border as mutable. Every city has different geographical, ecological, and sociological factors that affect it—there is no one solution. However, neither master plans for mass relocation nor reliance on free market incentives should dictate the shape of an urban form—the hierarchies they impose are fit for neither land nor water.