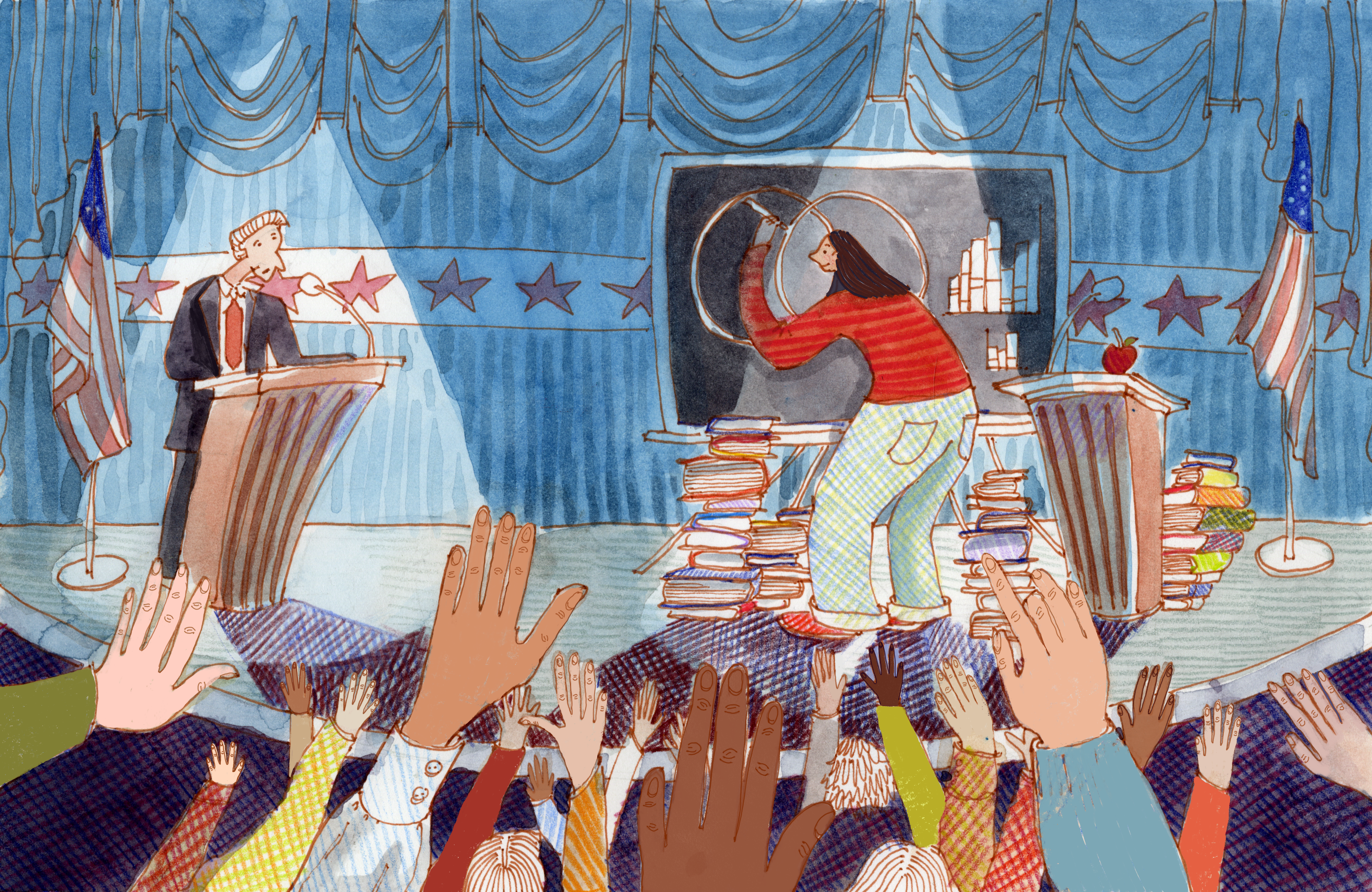

Since his name entered contention as Vice President Kamala Harris’s running mate, Tim Walz mania has swept the Democratic Party. One CBS poll found that 60 percent of Democratic voters were enthusiastic about the pick, while another 35 percent were at least satisfied. In their first joint rallies, Harris and Walz turned out crowds in the tens of thousands. Even outside the Democratic Party, Walz sports the highest favorability rating of anyone on either presidential ticket. This enthusiasm and popularity is no surprise. Walz is everything a Democratic Party desperate to reconnect with its working-class roots and regain its populist appeal is looking for in a politician: He’s a veteran, a dad, a former football coach, a Midwesterner from a small town, and perhaps most interestingly, a former public school teacher.

This last quality stands out in a party dominated by lawyers. Every Democratic presidential nominee since former President Jimmy Carter was a lawyer before entering politics, with the exception of former Vice President Al Gore, who attended but never finished law school. Almost half of President Joe Biden’s cabinet has a law degree. However, these party demographics—where lawyers are the norm and teachers the exception—are the exact opposite of what most voters say they want. A 2023 poll conducted by the Center for Working-Class Politics asked voters which professional background they would most want a hypothetical candidate to have; the most popular response was “Middle-School Teacher,” and the least popular was “Lawyer.” This finding held true for voters in general and for Democrats specifically.

There are some obvious explanations for why voters would rate teachers so favorably and lawyers so poorly. Teachers are public servants devoted to one of the most noble, least objectionable causes: educating children. They are intelligent and highly educated but still perceived as blue-collar. Lawyers, on the other hand, generally exist in the public consciousness as the epitome of sleazebaggery, swindlers who sell themselves to the highest bidder and say fancy words for too much money. These perceptions alone could account for the relative popularity of each kind of candidate, but another plausible explanation is that voters are rejecting the governing philosophy lawyers have represented and are instead embracing the governing philosophy teachers could represent—a philosophy Walz has embodied throughout his tenure as Minnesota’s Governor.

How social science and history teachers like Walz conceptualize government differs fundamentally from lawyers. The practice of law requires an understanding of government on paper—of the statutes and regulations it produces. The practice of teaching government requires breathing life into those often-dull concepts, bridging the divide between the legislator’s pen and the student’s reality. Teachers make laws, regulations, and government tangible and comprehensible for their students, requiring an intimate understanding of how those institutions operate. These characterizations are of course generalized: teachers have to understand how laws and regulations exist on paper, and lawyers often have to explain the law in layman’s terms. But broadly, these generalizations reflect what is essential to each job and therefore how members of each profession might approach designing policy.

The respective position of each profession within government could also impact the way each views governance. Teachers occupy one of the few government positions that consistently, directly, and intimately interacts with the American public, and this outlook may make teachers-turned-politicians more inclined and better able to craft robust public programs that straightforwardly benefit their constituents. Many lawyers-turned-politicians, on the other hand, started their careers in prosecutorial or inward-facing government roles as US attorneys or legal counsel to politicians and legislative committees, which could dispose them to policymaking that is aloof and technocratic.

The Democratic policy agenda over the past several years feels distinctly influenced by the legal backgrounds of the people creating it. The Obama administration’s priorities and governance were technocratic and procedural, the effects of the policies it championed hardly noticeable and unremarkable for all but the wonkiest of policy wonks. Its signature achievement, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), was less a comprehensive remake of healthcare policy and more a patchwork of different regulations, subsidies, and mandates whose rollout was marked by incompetency and administrative failure. In other words, the ACA would have made perfect sense to a lawyer well-versed in the American healthcare system and the laws and regulations that govern it but considerably less sense to the people meant to benefit from it.

While Biden’s agenda was a departure from his Democratic predecessor’s, it too often emphasized policies that only obliquely benefited ordinary Americans. Even when the Biden administration did work toward popular, straightforward policies, it made them temporary or couched them deep in elephantine spending plans like the Build Back Better Act (which also contained many not-so-progressive provisions). In the end, the policies that were actually enacted included allowing Medicare to negotiate the prices of specific prescription drugs—which will theoretically benefit Americans but in the most roundabout way possible by reducing federal budget deficits. Meanwhile, policies like an expanded, fully refundable child tax credit—a policy with a direct and tangible impact on the pocketbooks of American families—were temporarily enacted but allowed to expire. Many of these choices could be more broadly attributed to an out-of-touch political class, but the Biden administration’s emphasis on policy projects that are too weedy, too indirect, and too focused on barely-visible procedural reforms smacks of lawyerly influence. It is no wonder that only 17 percent of Americans believe that the Inflation Reduction Act, one of Biden’s signature legislative achievements, will benefit American workers, according to an AP/NORC poll.

Contrast this record with Tim Walz’s. Walz helped steer through legislation that enacted big, bold, and straightforward public programs that directly and noticeably impacted the lives of Minnesotans. Perhaps the highest profile policy that Walz championed was a universal free school breakfast and lunch program that explicitly rejected any of the bureaucratic complexity that would accompany a means-tested alternative. Walz also created an expanded, fully refundable child tax credit with no expiration date, established paid leave and paid sick days, and passed the largest investment in public education in Minnesota’s history. Minnesotans do not need to be lawyers or policy wonks or even pay attention to the news to understand how Walz’s legislative agenda has benefitted them and see the salutary effects of government programs on their lives.

Mainstream liberal thought has become far more friendly to big government in the past several years, as embodied in the shift from the Obama administration’s legislative aims to the Biden administration’s. However, that shift was not fully realized, perhaps in part because of the incongruity between the policy design required to create effective public programs and the lawyerly dispositions of the people designing Democratic policies. Unfortunately, despite Walz’s meteoric rise, the Democratic Party is still a party of lawyers and probably will remain so for the foreseeable future. But Walz’s success signals discontent with that status quo and offers an alternative way forward, a more effective and potentially more electorally successful model of governance that public school teachers are uniquely suited to provide.