Orbiting more than 225 thousand miles from the Earth, the Moon is more than a pretty sight in the sky or a conduit for human exploration: It contains valuable natural resources. Considering the Moon’s vast reserves of Helium-3 (better known as H-3, an otherwise rare resource that would expedite nuclear energy advancements), ice (and therefore water for fuel creation, making the Moon a pit-stop to Mars), and various metals and minerals that could be used for consumer technologies, there is a clear incentive to harness lunar resources. These resources not only have the potential to aid future self-sustaining lunar stations but also offer more immediate opportunities to provide value back on Earth.

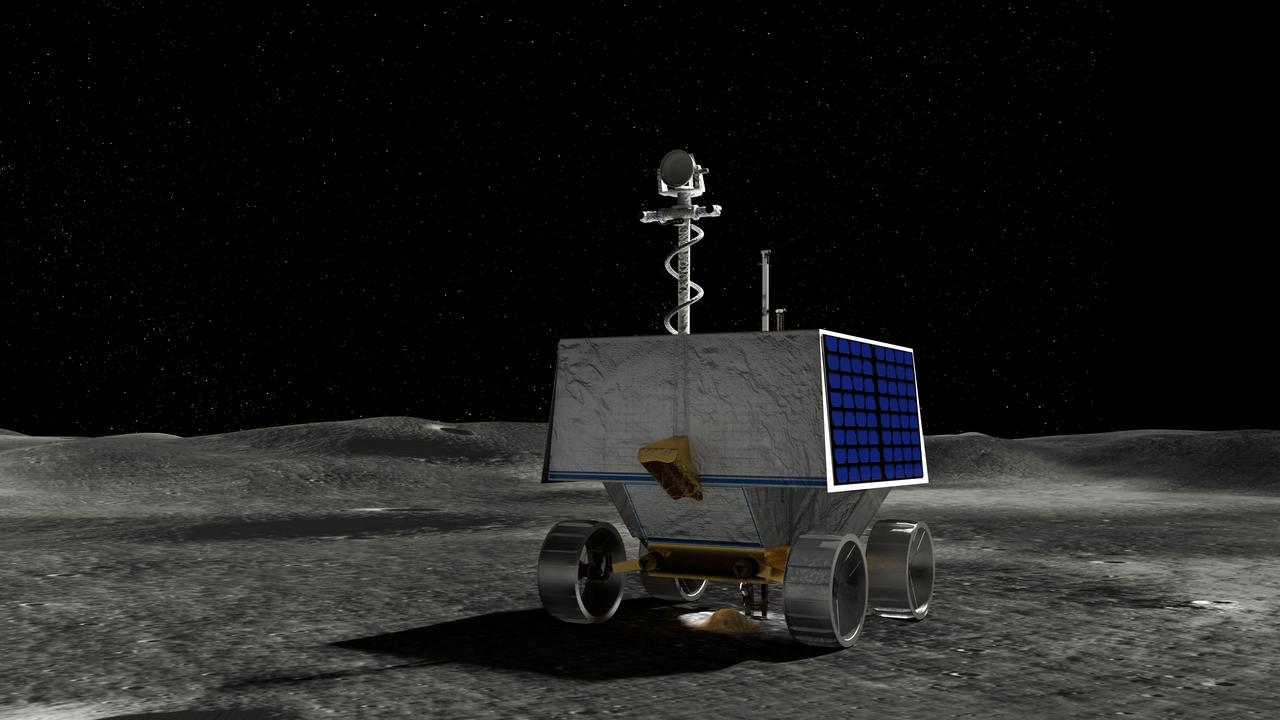

Currently, NASA is developing a system to deliver H-3 to Earth, and China–the US’s leading space rival–is interested in H-3 extraction as well. Private actors have also joined the fray: AstroForge aims to mine metals from asteroids, while others like Interlune plan for H-3 collection as early as 2028. While lunar sustainability and the market potential of space advancement often dominate space policy debates, one unanswered question looms in the background: Who owns the rights to the Moon’s resources?

Current frameworks and treaties fail to provide a clear answer. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty provides that no state may claim ownership of any space body but leaves open the possibility of extracting resources without claiming sovereignty—an interpretation the US explicitly endorsed in its 2015 Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act. A similarly strategically vague regulation attempt are the Artemis Accords—a product of the US-led space bloc—which call on nations to act multilaterally concerning space resource extraction but do not give specifics or a timeline, allowing for de facto unregulated extraction. Most recently, the 1979 Moon Treaty proposes a new international regime under which states should share Moon resources. However, this treaty is not supported by major spacefaring countries such as the US, Russia, or China and, as a result, has little relevance to actual policy.

In an unregulated system, a bad actor could theoretically create and defend a militarized base on a large mining site or monopolize H-3 extraction and charge an inflated monopoly price, harming all who could benefit from this vital energy source. Less extremely, any disagreement about policy between countries is bound to stir unrest and discontent, putting the norm of peaceful space behavior in jeopardy. One accident or dispute between foreign corporations could easily escalate into open violence without proper mechanisms for communication or resolution. Given these concerns, the US and China—the two leading spacefaring countries—must lead the international community in creating a consensus-based framework to proactively address emerging space resource extraction disputes, with clear guidelines that prohibit extraction until multilateral permission is obtained. While such a system would admittedly delay profits, comparisons to a successful and similar deep-sea extraction regulation regime show its merit.

The deep-sea—formally ocean area 200 miles from shore and outside the jurisdiction of any country—parallels the Moon’s status as a resource-rich, unclaimed domain. Amazingly, despite clear individual incentives to mine in the deep-sea, 169 states and the European Union have committed to a rules-based approach for deep-sea resource extraction under the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a framework that enables communication, prevents conflict, and ensures peace. While there are certainly differences between sea mining and space mining that regulation must account for, the general principles of international sea mining governance could apply to and greatly benefit space.

The ISA is governed by a 36-state policymaking body that decides ocean-extraction regulations by consensus, requiring fairness and cooperation from each state to advance policy. Such an approach is feasible despite its sluggishness because space and sea resource extraction are not urgent to daily economic functioning or national security. In the same way, because large-scale competition for space resource extraction is still a few years ahead, international regulators have significant time to settle disputes and set regulations without profit losses. Finally, as seen after the ISA regulation deadline extended from 2023 to 2025, stretched timelines and greater international participation allow more room for scientific research to influence regulations, prioritizing sustainability over profit motives. If space mining was regulated similarly, it would ensure that space resources, like ocean resources, would be enjoyed by many, not few.

The ISA’s process for allowing states to deep-sea mine is also relevant to space mining regulation. Instead of setting vague rules for states to follow or break, the ISA will grant authority to mine in international waters through individual, many-year-long project permits. Such permits must be lobbied for by a state or company and are approved on a case-by-case basis, ensuring proper environmental practices, peace, and the equitable distribution of the spoils of extraction. If a similar system regulated space mining, no spacefaring state or its corporations could dominate a resource or territory without explicit permission from other states. Most states would likely refrain from irrationally objecting to another state’s proposals because they would fear a tit-for-tat response. While one could argue that it is impossible to force countries to comply with such a process, states could easily observe unauthorized space launches or territorial claims. As a result, states would be deterred from defecting from the agreement—as they would face backlash, sanctions, or worse—and would have little fear that other states had already secretly defected, another common cause of treaty breaching.

The principal problem in comparing the regulation of sea mining and space mining is that the US–one of the two top players in space–has not joined the ISA, acting only as an observer who cannot apply for permits. This status likely comes from the US’s reluctance to ratify the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea—which established the ISA—because of conservatives’ concerns that the protocol will violate American sovereignty and make the US liable to foreign environmental standards. As is true with many treaties, the US can afford not to sign because of its status as the world’s leading terrestrial power. Unfortunately for the US, but fortunately for peaceful space relations, no modern nation enjoys such comfort regarding space exploration and resource extraction.

Today, while it is clear that the US and China are the world’s leading space powers, the distinguishability of relative strength between the two is less certain—especially following China’s successful Chang’e-6 mission, which gathered the “first ever samples from the far side of the moon” in June 2024. Without a clear understanding of who will come out on top, both sides must be wary of the other reaching, claiming, and defending all resources from the other. As such, it is in the interest of both nations—and all others—to create a regulatory system to handle space extraction, giving up potential monopolies to guarantee long-term access to resources. Considering the economic and security implications of space and resource extraction, this topic must be addressed before large-scale collections begin. A system like the ISA, which combines a consensus-based decision-making process with a permit-based extraction system, would ensure thorough, cooperative space regulation that would prevent any single state or company from obtaining outsized power over space mining or claiming territory unilaterally. Such a foundation for space diplomacy would ensure that space extraction proceeds smoothly and likely cause spillover benefits into other space-related disputes, like those around claiming territories for long-term bases. If, instead, states act aggressively toward extraction, they will not only risk their own security and economic prosperity but also humanity’s slim chance at a peaceful future in space.