The BPR High School Program invites student writers to research, draft, and edit a college-level opinion article over the course of a semester. Catherine Xue is a senior at Bellaire High School.

Donald Trump shot during a Pennsylvania rally. Charlie Kirk assassinated at Utah Valley University. Governor Josh Shapiro’s home in flames after a Molotov cocktail was thrown into his dining room. State Representative Melissa Hortman murdered by a man dressed as a police officer; Senator John Hoffman shot moments later. Governor Gretchen Whitmer almost kidnapped over Covid-19 restrictions. Paul Pelosi attacked in a home invasion by a man who thought Democrats committed crimes to steal the election from Trump. And a man crashed a jeep full of knives and nails into the White House gates.

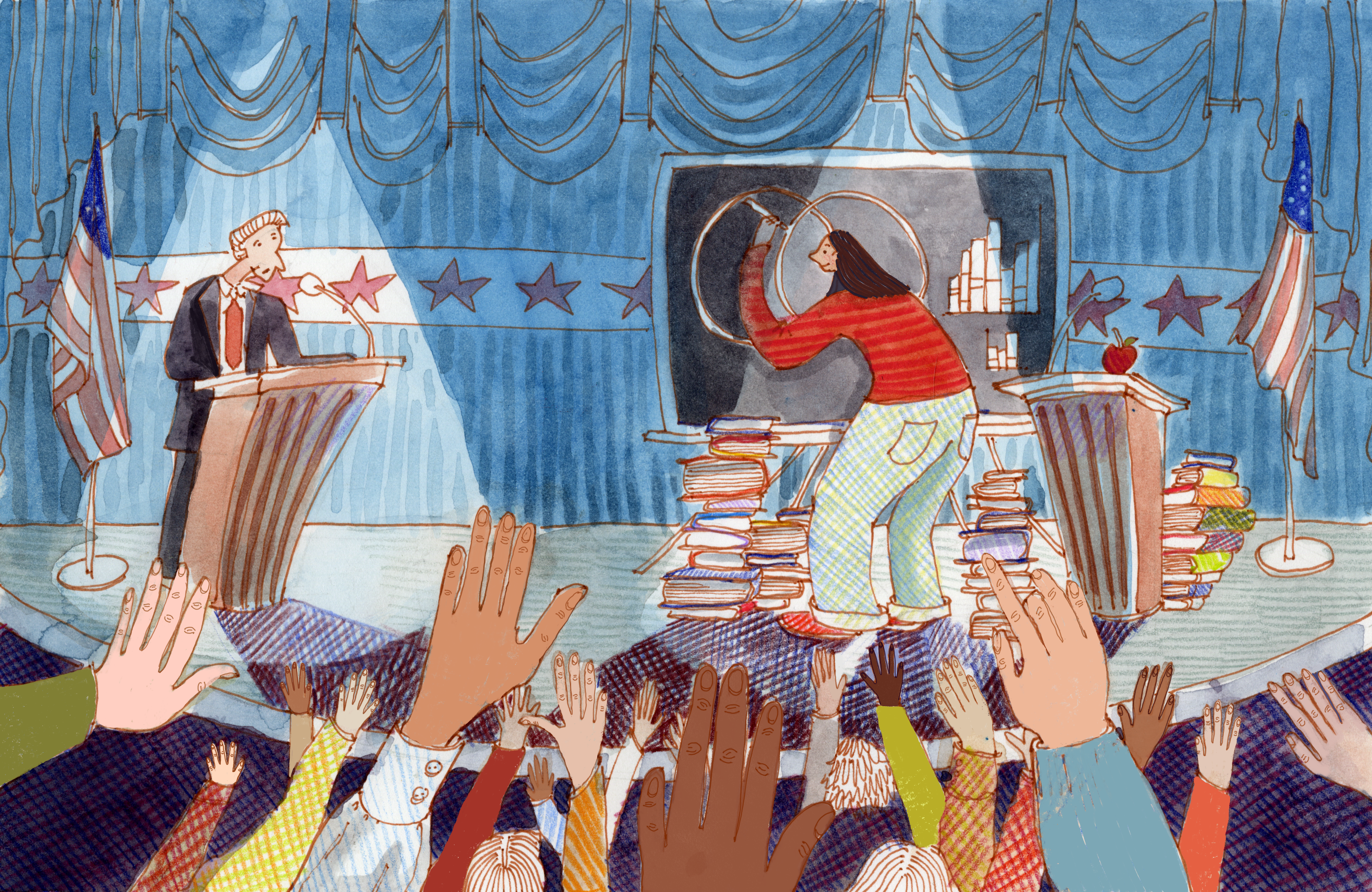

These incidents of politically motivated violence, unfortunately, represent a larger, rising trend plaguing the United States, with 49 percent of attacks from 2016 to 2023 being driven by partisan political views. Given the rise of violence against political figures in the United States, the country needs to curb political polarization and combat one of its root issues: civic illiteracy.

The general decline in civic education began in the 1960s, when the Vietnam War and Watergate scandal decreased public trust in the government and many viewed civic education as assimilation and “cultural imperialism.” As a result, high schools opted to phase out civic education and stopped requiring three courses in government and civics. Today, civic education is at an all time low. Over 70 percent of Americans failed a basic civic literacy test with questions asking to name the three government branches, number of Supreme Court Justices, and the basic functions of democracy. However, this isn’t a surprise given that over half of eighth grade students have not taken a civics or government course. The lack of civic knowledge isn’t unique to students, as less than 25 percent of secondary preservice social studies teachers could even name their state’s senators.

The rise of violence and lack of civic education warrants increased investment into civic education to foster effective civic discourse and mitigate the impacts of political polarization. By exposing students to civic knowledge, the negative effect of partisan polarization can be decreased by 22 percent, especially in countries suffering from intense partisan conflict, like the United States. When Americans understand how the government respects the separation of powers and manages influences from lobbyists, the media, and politicians, they are more likely to see past partisan cues and be less susceptible to political manipulation because they understand past precedence and common tactics used by politicians to try to garner votes. Investing into civic education protects voters from deception, whether it’s cherry picking statistics or using extreme language like “corrupt” and “pathetic” to describe an opposing party, empowering them to make decisions based on evidence rather than emotion.

Critics argue that civic education is “too divisive” to teach in schools because it covers documents like the Constitution and political systems which draw controversy due to conflicting interpretations. Even if this is the case, the harm of not teaching civic education outweighs avoiding the topic altogether. The fact that 87.5 percent of teachers self-censor due to fear of controversy and backlash from parents isn’t a reason to retreat from civic education but to double down on more definitive standards and concrete resources for educators, especially as fewer than 15 percent of teachers were given clear instruction on what was acceptable to teach. With stronger guidelines, teachers would be more willing to have conversations with students about relevant curriculum because they have a framework to fall back on for support.

Right now, the most significant challenge surrounding civic education is deciding who implements it. With fluctuations in funding and new priorities with each presidency, federal involvement often creates an unstable foundation for civic education with officials prone to polarization, whether it’s because of bribery or the adoption of polarizing campaigns to win voters. Every four or eight years, a new administration with new agendas and priorities will take over, and there’s no telling what they’ll do. Keeping civic education separate from these uncertainties is a safety net for it, protecting it as administrations come and go.

The same issue lies within the states, no matter their political affiliation — partisanship drives policy whether it’s Texas lawmakers requiring the Ten Commandments to be displayed in public schools or Rhode Island making African history and heritage mandatory in K-12 public schools. Civic education varies from state to state, but only 26 states cover democratic principles like the rule of law or government accountability, the Constitution, civic engagement, voting, and media literacy. It’s clear that inconsistent and inadequate civic education in the hands of states doesn’t promote understanding. Instead, it’s a breeding ground for disengaged students who will become ignorant constituents who fall prey to polarizing rhetoric. Polarization is so entrenched in the government, so how can we trust them to roll out an objective curriculum?

All options considered, nonpartisan third parties may be the best way to create an unbiased course of study. Working with third parties is attractive to schools because as it provides resources the school or district cannot, so even underfunded schools can access high-quality support. Take iCivics, a nonpartisan civic education organization founded by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor that provides free material and has reached 80 percent of US counties. The organization is led by an independent review council with professors, teachers, and researchers with a variety of different viewpoints, ensuring its lesson plans are accurate, objective, and neutral. When provided with the right resources and support, such as games for students or course plans for teachers, 95 percent of iCivics teachers reported increases in engagement and openness to civil conversation in the classroom. Most school districts, especially larger ones, have formal curriculum review committees to evaluate nonprofits like iCivics before they decide to partner with them. While iCivics is completely free, the Center for Civic Education offers both free and paid resources. In this case, they may go through a request for proposal process, where schools, districts, or state education departments hire organizations after a competitive bidding process.

That’s not to say that civic education should be put solely in the hands of third parties. Rather, there must be safeguards in place to protect civic education from all levels of government, at least in terms of funding and leadership, to prevent politicians from having the leverage to push their own agendas. To achieve this, the federal, state, and local government could create nonpartisan committees to oversee the approval process for grants, ensuring that unbiased organizations get the necessary funding to curate guidelines. Financial endowments could also be established to provide steady, long-term baseline funding for civic education during times of extreme political uncertainty.

At the same time, it’s not just about policy solutions, but also about instilling civic values ground-up through civic organizations and communities, which is ultimately more sustainable than just having government reform. It does not matter if you are a Republican or Democrat, liberal or conservative: the true cost of an uneducated constituency is the degradation of democracy.

Unfortunately, the reality is that there is no one-size fits all solution to polarization. It’s a multifaceted issue requiring widespread societal reform—but progress can start in the classroom.