A response to “Nuclear Iran, Safer World” by Omar Ben Halim

by Katherine Long

While I agree with Mr. Omar Ben Halim that a nuclear Iran could be capable of balancing Israeli power and lead to a more stable Middle East (“Nuclear Iran, Safer World?” Vol. 1, Issue 2), I take issue with many of the points he marshals in support of his thesis. A more nuanced analysis of Iran’s internal affairs might have led Mr. Ben Halim to a different conclusion.

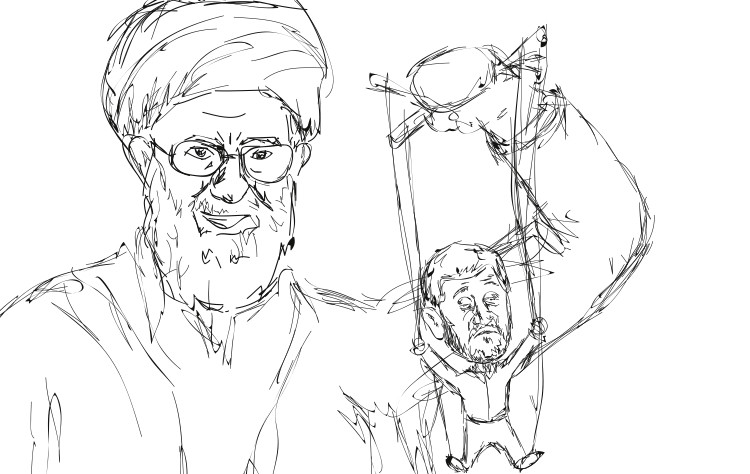

The author’s first mistake is to overestimate President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s influence within the regime. The structure of government in Iran does not give the president control over the army. Additionally, in light of not only Iran’s rapidly approaching presidential election in June but also the less-than-covert power struggle between President Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei—a struggle in which Khamenei came out on top—Ahmadinejad’s power base is weaker than ever. The New York Times recognizes that neither he nor his cabinet control policy. Ahmadinejad is a glorified figurehead; it is a mistake to conflate his “unsubstantiated bluster and inflammatory foreign policy” with the views and actions of the “highly intelligent and rational” ulama who truly control the country. Brown Political Review’s illustration, featuring a bust of Ahmadinejad behind a pile of nuclear weapons—thus linking the president to Iran’s nuclear program and implying that he has some measure of control over it—did not help debunk this misconception.

Nor am I capable of accepting Mr. Ben Halim’s conclusion that upon obtaining a nuclear weapon, Iran would necessarily cut off funds to Hamas and Hezbollah. Why would an “intelligent and rational” group of individuals forgo such access to avenues of influence? Funding Hamas and Hezbollah is a potent bargaining chip for the Islamic Republic. It is conceivable that upon obtaining a nuclear weapon, Iran would agree to stop funding Hamas and Hezbollah in exchange for a reduction in sanctions, but suggesting that the first necessitates the second is a mistake.

Moreover, the author fails to distinguish between American political rhetoric and actual policy. Hawkish United States congressmen have been making noise about attacking Iran for decades, but the tacit consensus has been a policy of coercive diplomacy. It is inconceivable that America would attack Iran. As Ben Halim notes in his article, Iran is a “country of 75 million people”—who despite widespread dissatisfaction with the revolutionary regime would fight tooth and nail against an American occupation.

Downplaying this dissatisfaction, however, is the author’s largest error. He assumes that, because the Islamic Republic has been able to maintain power in Iran for “over 30 years,” it is stable enough to be trusted with nuclear weapons. This is not necessarily the case. The popular uprisings of the Arab Spring repeatedly destabilized regimes that had been in power for 58 years (Egypt), 42 years (Libya) and 43 years (Syria). Clearly the length of time that a regime has remained in power is no guarantee of internal stability. Furthermore, the author ignores signs of destabilization in Iran: the Green Movement, drug shortages, the plummeting value of the rial, and hints that June’s presidential election will be the least open in the history of the Islamic Republic.

The fact of the matter is that Iran will probably develop a nuclear weapon sometime in the future, and, rhetoric aside, there is no real support among policymakers in Washington for an attack on Iran, meaning coercive diplomacy is off the table. So what happens if—and when—a nuclear Islamic Republic crumbles? Its weapons, more likely than not, will end up in the hands of terrorists. In the words of Austin Long, professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University, “The world might be forced to choose between hoping the Iranian regime crushes the uprising or risking the Iranian nuclear arsenal becoming uncontrolled.”

This in and of itself is reason to oppose a nuclear Iran, despite the ease of containment and a potentially stabilizing effect on the region.

Katherine Long ’14.5 is a Middle East Studies Concentrator.

Submit your letters to: comments@BrownPoliticalReview.org