This week, I originally planned to write of a new and recent phenomenon, the assumption of China as the globe’s leading importer of oil, a heavy title the U.S. has carried for nearly the past forty years. The implications of this shift can and will be analyzed at great length–perhaps next week I will have a go at it. But this week, I found myself compelled to write about something a little more abstract, entirely more subjective, and no doubt more of a magnet of criticism. I was recently assigned a fascinating book in one of my classes, a work aptly titled The Korean War: A History. In it, author Bruce Cumings focuses on the sociological as well as political aspects of America’s “Forgotten War” (for it is hardly forgotten in Korea), analyzing the context in which the conflict in Korea has become largely unknown in a collective American unconsciousness. Much of his conclusion has to do with American perceptions–of war, of Korea, of Asia in general, and of communism.

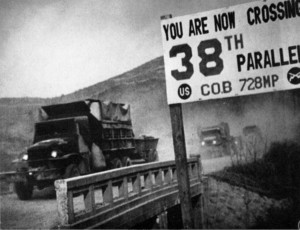

In that vein, I want to talk this week about perception, mainly about how current Western perceptions of the East came into being–and the effects these perceptions might have on the relationship between these two regions today. To begin, it is acknowledged that to divide the world into East and West is an inherently conflictive action. But seeing as a large portion of global history has relied on this distinction, it has become a sort of self-fulfilling division, and thus a necessary context. It is nearly impossible to examine East-West relations as far back as they have existed, and so it is perhaps more fitting to examine them in the context of the past fifty years–since the end of World War II–a period which witnessed the establishment of communism in Asia. By 1955, Mao Zedong was comfortably installed in a communist regime in China, and Kim Il Sung commanded the communist Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea. In place after decades of war, bloodshed, and imperialism were the power structures that have largely lasted through the Cold War to this day, and the American conceptions of national identity that went along with them.

These conceptions of national identity have largely remained unchanged, even as the Cold War period in which they were formulated seems to have long passed. Indeed, to say we live in a “post-Cold War” world today is a gross oversimplification, for America, even if not in the throes of McCarthyism, seems to regard North Korea as inherently “other” because of their communist regime. There consequently exists in the West a persistent refusal to accept North Korea as a viable political entity. Throughout the world, and even in their neighbor China, North Korea seems to be alternately a laughingstock or, at least if you are George W. Bush, “evil.” Many point to an admittedly deplorably long list of humans rights violations committed by this nation as reason, yet ignore the fact that Germany and Japan, who committed atrocities beyond words in achieving their imperialist ambitions in the first half of the 20th century, were deeply embraced by America during the post-war years. Both Germany (Eastern Germany after 1989) and Japan are great capitalist success stories who since 1945 have deepened ties with America every step along the way to economic prosperity. North Korea, of course, remains the sole Stalinist state in the world.

This is in no way an argument for extreme socialism, or an acceptance of North Korean human rights abuses. If any sort of truth can be gleaned from the past seventy years, it is that state communism of the sort North Korea is now alone in practicing does not work. Rather, I believe that economic progress can and should come to North Korea (as it is to China) in the form of global capitalist integration, and that with it will come an improvement in the area of human rights. Yet no true change can be brought about in North Korea until Western states stop seeing the nation as something nearly inhuman and start seeing it as a nation like any other. By humanizing North Korea, we can begin to remove a stigma that currently envelops the entire state, and one that stands in the way of true progress. What we need in our thinking is a fundamental shift in the way we think about East and West or “us” and “them.” Still bound by antiquated Cold-war sentiments, the U.S. can not afford to keep portraying themselves as the world’s “good cop” to North Korea’s (and, to an extent, China’s) “bad cop.” Such an oversimplification plays right into the hands of a Northern Korean government that still seeks to paint Americans as ignorant.

All this is not to say America and other Western countries do not have a role in helping to solve problems of the sort China and North Korea experience. Rather, it is clear that neither China nor North Korea can exist on their own, as evidenced by the prosperity of an opening China and the abject poverty of a closed North Korea. These two countries know this fact. And so it is time to stop thinking of these states, particularly North Korea, as pseudo-psychotic and start thinking of them as they really are, as rational entities, if only to have a chance of ever instituting sensible dialogue with this region of the world.