George Orwell’s canonical work, 1984, warns of a future in which the all-powerful ‘Big Brother’ dictates truth by rewriting history so that only one version of the world can exist. Orwell frames this dystopian dictatorship as attempting to dilute the meaning of language to narrow the realm of public thought: “It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words,” a representative of the dictatorship tells the book’s protagonist. While thankfully this future did not come to pass, our reality may be far more sinister.

In 21st century American politics there is no Big Brother, nor is there one interpretation of reality. While Orwell predicted a dystopia of a singular sociopolitical narrative, the crises of the modern era have indicated something quite different: thousands of sociopolitical narratives, many of which are misinformation that thrives on uncertainty. Today, there are millions of narrators, each crafting their own version of events that distort the truth. Authority over our information networks is not concentrated in one body, but rather dispersed across platforms—such as TikTok and X—where users create conflicting versions of reality that offer clarity in moments that feel unstable. In this environment, emotionally-charged political narratives are rewarded while inert facts are punished. Orwell imagined a future of state-controlled censorship, but today, the internet’s competing fictions have been weaponized into an emotional contagion that spreads quicker than disease. From anonymous conspiracy theories like QAnon to AI-generated deepfakes, misinformation persists in society not simply because it exists in abundance, but because it offers security, clarity, and moral coherence during times of chaos.

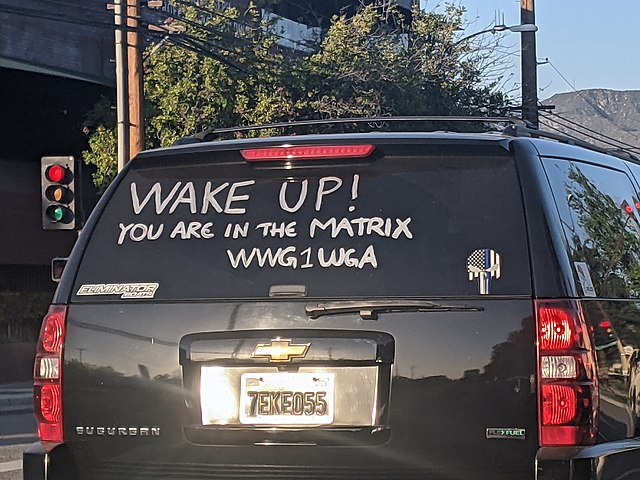

QAnon was one of the first cases of digital storytelling that allowed the public to participate in political narratives. The conspiracy emerged in 2017 when a mysterious account called ‘Q Clearance Patriot’—or simply “Q” — began posting on the imageboard 4chan. Q’s posts unfolded into a disturbing political narrative claiming left-wing politicians and government officials were running a secret child sex trafficking ring, controlling the media, and manipulating financial and political systems. Q presented Donald Trump as a savior who was working to dismantle this corrupt system, efforts which would be revealed in an event they dubbed “the Storm.” Eventually, Trump—according to Q—would purge evil from the world. In August of 2020, Trump finally commented on the conspiracy theory, referring to the QAnon coalition as “people who love our country.”

Q’s followers became obsessed with this narrative. As online message boards deciphered Q’s cryptic “info-drops,” fan theories emerged and online communities formed around a shared interest in the moral drama spun by Q. QAnon attracted an audience because of its legibility—its ability to mold moments of political chaos (pandemic, economic precarity, and political polarization) into an emotionally satisfying story of heroes and villains. In the months leading up to the January 6 insurrection, message boards spread the sentiment that violence was necessary to save the United States. The insurrection saw political fiction break free from its online containment and into the real world. The rioters on January 6 filmed the event, wore costumes, and even posed for the media when given the opportunity. In other words, they were able to become actors in the political narrative that they had spent years following online. As the narrative reached its climax, followers could get into character and take on a role in their favorite cult-classic. QAnon engaged an audience the same way novels, movies, and other plot-driven storylines do. The narrative provided moral coherence and community—a comforting simplification of the political climate as opposed to its violent reality.

This same impulse provoked the viral spread of Plandemic in May of 2020. This 26-minute documentary accused the global elite of unleashing the Covid-19 virus in order to control the population, and suggested pseudoscientific treatment alternatives while dismissing vaccines and mask-wearing. But the documentary’s form was as important as its content—Plandemic featured cinematic cuts and foreboding music to communicate a sense of moral urgency, appealing to an anxious public desperate for an ounce of understanding. In this sense, misinformation in the form of a documentary provided a means of relief during a time of pandemic uncertainty. The documentary provided the audience with a sense of security and faith that what they were hearing was rooted in truth. It also simplified reality, portraying the world through antagonisms between the corrupt scientists and the brave producers who revealed their crimes to the public. As information rooted in fact was either evolving, uncertain, or difficult to interpret during the pandemic, the false narrative the documentary provided gave the illusion of coherence compared to the reality offered by health experts. The agonizing quarantine could be repackaged as an act of oppression: a classic good versus evil storyline.

Today, the most pressing political storyteller is not a singular human or a network of human producers, but an algorithm. A more recent, and certainly more alarming, form of political storytelling has anchored itself in the public eye: AI generated deepfake videos of politicians, which blur the line between reality and simulation. Take, for instance, the notorious deepfake of former US President Joe Biden in 2023 that circulated widely across social media platforms. In the video, Biden announces a national military draft in response to the Israel-Hamas conflict, telling the public that “you are not sending your sons and daughters to war. You are sending them to freedom.” Later, fact checkers determined that the video had been fabricated using generative AI. Since this incident, several other deepfakes of major political figures have proliferated in the digital world. With the ability to fabricate hyper-realistic evidence, digital fiction can spread as truth. Although generative AI platforms (and the resulting deepfakes) are manufactured by humans for human purposes, AI allows a single creator to generate an endless stream of emotionally resonant misinformation. In this model, misinformation is both mass-produced and targeted. As such, deepfakes can and will function as a modern-day assembly line for digital misinformation by collapsing fact into fiction and spreading it faster than ever before.

The creation of AI-generated articles, synthetic news anchors, and even widespread deepfake videos of politicians all make misinformation and distorted political narratives more believable and more widespread. Unlike earlier conspiracies, such as QAnon, which relied on the charisma and craftiness of a single human author, AI-authored narratives can synthesize and fabricate the voices of several “authors” at once, reproducing political fiction rapidly. This shift towards algorithmic storytelling has transformed how misinformation is communicated—from human-to-human connection into an automated process where individuals capitalize on AI tools to fabricate emotionally resonant stories. AI makes algorithms more effective by analyzing what we consume and believe in greater depth to optimize engagement.

If Orwell’s Big Brother mandated a single distorted version of truth, AI has the capacity to create millions of versions. AI generates thousands of narratives tailored to individuals based on its study of their emotional profile. By gleaning from sources such as YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook, algorithms learn not just what users consume but what they feel. And whether that be outrage or hope, pain or relief, AI has the capacity to manipulate it.

And yet, political narratives of misinformation are sustained not simply because of deception and technological advancement, but also because of a deeply-rooted human desire for moral coherence and emotional resonance. Whether the author is an anonymous account or an algorithm, these political narratives remain enduring because they provide clarity in times of chaos.