We live in troubling times. Protests, wars, coups, government corruption, crime and acts of terrorism are just some examples of the violence and pessimism that permeate global news. Despite a common belief in the boons of globalization and international peacekeeping institutions, conflict is still undeniably one of the main drivers of world history. An iPhone update from the AP or a cursory click on the New York Times website is all it takes to remind us. But while many of us read about conflict while sitting comfortably in our dorms, the people providing the updates often take massive risks to provide us with the coverage we have by now taken for granted.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalism, 2013 was the second-most dangerous year for journalists since 1992, the year the organization began to keep track of reporter deaths and jailings. At least 70 died, 212 were imprisoned and at least 60 were the victims of violence and abduction. 124 of those imprisoned were accused of anti-state charges like terrorism or political subversion.

The geographical distribution of abuses against reporters followed somewhat predictable lines. China, Iran and Turkey accounted for more than half of all the journalists in prison in 2013. State control of news dissemination, censorship of critical media and criminalization of coverage of taboo topics such as the Kurdish Worker’s Party were the main reasons for these imprisonments. According to the report, China is the world’s largest reporter and internaut prison, accounting for two-thirds of the world’s imprisoned journalists and bloggers as of December 2013.

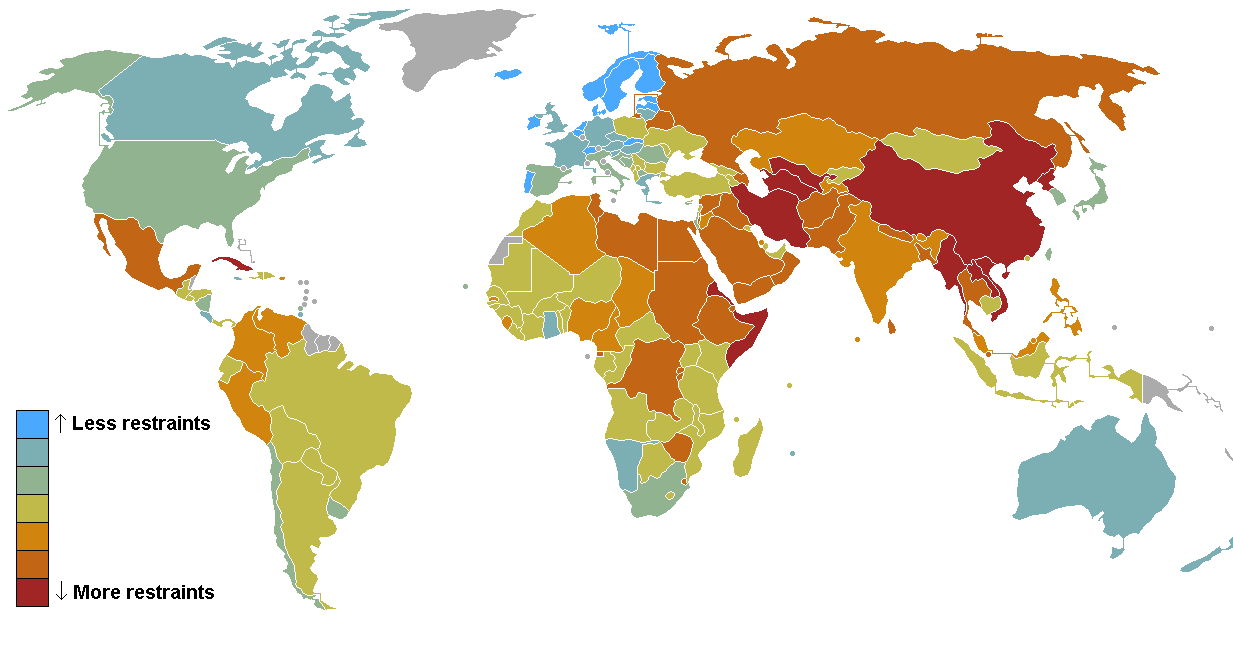

Reporters Without Borders, another organization focusing on journalist safety, released a ranking of countries based on the ease of reporting and the freedom of the press within their territories.

Countries like Syria, Somalia and Egypt featured among the most fatal in the world for journalists, primarily due to the spillover of armed conflict. Though this is not a new threat, there are some new dimensions to contemporary armed conflict that exacerbate the risk that reporters take. War correspondents, traditionally used to facing danger on the job, have been suffering from the new and unconventional risks of modern asymmetrical warfare. Multilateral conflicts like the one in Syria — where many actors with different agendas constantly encounter each other — expose reporters to unpredictable violence and make it practically impossible to find groups capable of protecting foreign journalists, let alone local ones.

Africa, with several autocracies and corrupt governments, is pockmarked with red spots on RWB’s map of press freedom, indicating a lack of media freedom in many of its countries. Coverage beyond official state news agencies is also very limited in several Middle Eastern countries.

An obvious takeaway from the CPJ and RWB reports is that liberal democratic countries outrank dictatorial ones in terms of transparency and media freedom. The organizations do not directly take political systems into account in their rankings, but it is clear that reporters in democracies face less obstacles when publishing and circulating accurate news. This is not to say, however, that all liberal democratic countries are exempt from fault.

While democracies like Finland, Norway and the Netherlands are consistently among the best places to practice investigative journalism, many European countries have gone down in the rankings in the last year. Corruption, shady anti-defamation laws and the failure to implement transparency laws in some administrations are some of the main obstacles to media freedom.

Other democracies, such as Brazil and Mexico, have seen so much violence directed at journalists by non-state actors that many reporters are essentially censoring themselves in order to protect their wellbeing.

Even the United States, the land of the First Amendment, has recently tarnished its track record by ramping up post-9/11 censorship and media control mechanisms. Coverage of the Snowden NSA leaks, and the Manning files sent to Wikileaks before that, was plagued by talk about the sale of “stolen material” by journalists covering the events. Many of the reporters working with the whistleblowers were deemed accomplices by elements in the U.S. government, which tried to persecute them legally as such.

It does not help that many of these obstacles are wide-ranging and diffuse. Apart from official censorship and defamation charges, reporters in many countries face difficulties from a variety of non-state actors that range from threats of bodily harm to the reduction of investigation budgets in cash-strapped news agencies. A particularly modern phenomenon, Internet censorship and hacking has also become some of the most troubling barriers for news dissemination. The threats presented by online censorship are especially dangerous for citizen journalists and online bloggers — who often do not have the institutional backing that professional reporters can count on.While 2013 was not the most perilous year for journalism, it came close to the record set in 2012. These two consecutive record-breaking years indicate that the world is increasingly becoming more dangerous for news providers, even as their jobs become more crucial. Its not just wars and wanton violence that makes the job harder. Many reporters, especially those on political beats, are beset both by the increasing securitization of government information and by the ever more urgent need to feed the global news cycle.

Perhaps more so than other industries, journalism is caught between responding to the imperatives of globalization or complying with the demands of national interests. Reporters increasingly see themselves as neutral actors, meant to provide information to a worldwide audience rather than to directly influence national events. Their labor of providing freedom of information is even enshrined in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, most governments — including the United States and Britain — have a hard time acclimatizing to unflattering exposure in the global news cycle. As a result, messengers are often targeted in lieu of the message.

Whether they are war correspondents in Syria, bloggers in China or investigative journalists in the United States, today’s journalists are the drivers of an industry that enjoys more influence and dissemination than ever before. The world literally runs on news media, with massive political and economic decisions being weighed against the impact they can cause in the information network to which most of us are constantly plugged into. News is ultimately the shaper of public opinion, both the source of its power and the reason it is targeted so fiercely. Tied in this way to the opinion of the masses, a free press goes hand in hand with democratic development. It is therefore the responsibility of democratic countries to lead by example, and to prioritize press liberties as much as any other indicator of progress in countries with incipient representative governments. If we’ve created such a need for constant and widespread information, its our responsibility to help make the job safer for those providing us with the updates we read every day.