The election of Donald Trump forced a reckoning among American Evangelical Christians. Faced with a candidate who seemed to at least superficially embody many of the characteristics Evangelicalism condemns, it appeared that Trump’s candidacy would puncture the trend of consistent Evangelical support for the Republican Party. But when voting white Evangelicals were asked what they would say to a President who faced numerous allegations of adultery and sexual assault, and maintained the lifestyle of a playboy real estate tycoon, 81 percent of them answered with a resounding “amen.”

Although it’s true that white Evangelicals harbored mixed opinions of Trump, support for him was uniquely high; by comparison, only 60 percent of white Catholics voted for Trump. According to the Pew Research Center, more white Evangelicals voted for Trump than they did for Romney (78 percent), McCain (74 percent), and Bush (78 percent in 2004). Many news outlets and analysts seemed shocked by the overwhelming white Evangelical support for Trump, and others claimed that support for such a lewd figure ran contrary to Evangelical religious convictions.

How could white Evangelicals support a candidate whose character seemed so obviously and fundamentally at odds with Christian morality? Whether it was a consequence of wishful thinking or a misunderstanding of the Republican Party’s relationship to white Evangelicals, pre-election rhetoric was littered with commentary about Trump’s incompatibility with pious Evangelicals.

But this commentary was misguided. Looking at the history of Evangelicalism within America, we see the faith’s frequent endorsement of entrepreneurs, strongmen, and a romantic conception of the free market. Trump’s election was just the latest chapter for a religious group with a history of cozying up to to business tycoons.

Of course, there are many reasons why white Evangelicals would plausibly have cast their ballot for Trump, including their distrust of Hillary Clinton as a presidential candidate, apprehension about globalization, and fear of terrorism. And yet their limited concern about Trump’s more impious qualities seemed counterintuitive.

Evangelicals seemed to vote for Trump largely because they viewed him as someone capable of alleviating their economic ailments and addressing terrorism, not out of regard for more traditional Christian concerns like abortion (only 4 percent of Evangelicals cited this as guiding their decision compared with 89 percent for terrorism and 87 percent for the economy).

To understand Evangelicals’ support for a business tycoon like Donald Trump, it can be helpful to briefly consider the historical relationship between capitalism and Evangelicalism in America.

Some of the Bible’s most famous passages clearly denounce wealth accumulation in mortal life. The Sixth Chapter of the Gospel of Matthew declares that Christians should “lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth… But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven.” That is, Christians should limit their attachments to earthly items and forgo ambition for mortal wealth in favor of investments in the afterlife.

But early American Protestantism presented a new interpretation of this conviction. Instead of encouraging followers to abide by a religious moral dogma eschewing current wealth in the interest of a prosperous afterlife, followers were encouraged to toil in their mortal existence and acquire wealth, property, and capital. This exhortation was leveraged not only by appeals to divine moral authority and God’s will; Protestantism contended that such hard work was utterly necessary to reserve a place in the afterlife. (This belief in a conditional election to salvation was perceived as more meritocratic than the unconditional election views articulated in Calvinism and Lutheranism).

The relationship between Protestantism and American capitalism is a well observed phenomenon. In Max Weber’s seminal The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, he contended that American capitalism was a natural consequence of the Protestantism that abounded in the nascent United States. According to Weber, the prevalence of a religion that emphasized toil and hard work fostered a culture that highlighted the importance of holding property and acquiring resources.

Weber comments that “Protestants… have demonstrated a specific tendency toward economic rationalism” and that the “Protestant Work Ethic” is thus bent on “the strict earning of more and more money, combined with the strict avoidance of all spontaneous enjoyment of life.” He points out that, while pre-capitalists would react to a greater wage by increasing leisure time, Protestants did the exact opposite, working longer hours. For Weber, this “Protestant Work Ethic” was unique in its emphasis on labor and wealth as a moral “good.”

The importance of Protestantism to both American culture and Christian identity cannot be overemphasized. As religious scholar Reza Aslan joked in a phone interview, if you’re a Christian in America, “you’re pretty much a Protestant.” Although the claim is hyperbolic, the point Aslan is emphasizing here is a valid one: that Protestantism, and the “spirit of capitalism” have left their mark on all American Christian denominations. One can see the enduring impact of Protestantism on Evangelicalism in the election of Donald Trump and the widespread support he received among white Evangelical voters.

Of course, it’s true that Evangelism — a transdenominational form of Protestantism — fundamentally differs from early forms of American Protestantism. And yet, despite their more literal interpretation of the Bible, Evangelicals have historically placed a similar emphasis on wealth, land, and labor. This cultural history has often compelled American Evangelicals to support romantic individualistic narratives and strongmen, while simultaneously integrating capitalist ideas into religious symbolism.

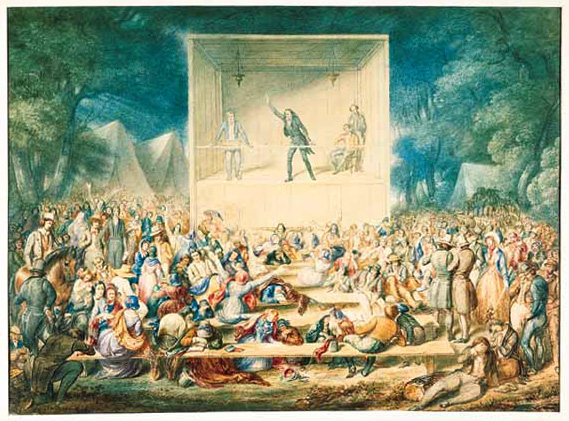

In the 19th century, this translated into Evangelicals’ enthusiasm for nationalistic, populist, and authoritarian tendencies under the banner of “Muscular Christianity,” a reading of the Christian doctrine which emphasized patriotic duty, manliness, self sacrifice, and “the expulsion of all that is effeminate, un-English and excessively intellectual.”

This marked a very distinct period of Protestant history in America. The young Teddy Roosevelt was famously raised in a household that emphasized “Muscular Christianity,” and elements of its influence can be seen in his rhetoric and virile presidential aura: he was a rugged sheriff who famously took down an armed cowboy with his bare hands. In addition to calling for the abandonment of “feminized” Protestantism and the embrace of more manly and aggressive attitudes, the “Muscular Christianity” movement romanticized the “rags to riches” stories of young, tough men who gained wealth through hard work.

Although “Muscular Christianity” is no longer a prominent force in American Evangelicalism, the disposition to support successful businessmen and strong leaders has persisted. From the early emergence of the Protestant work ethic to the modern Evangelicalism that it helped produce, there has been a consistent emphasis on individualistic success stories that are romantically cast as the hallowed conquests of strong and patriotic men.

The persistence of these narratives within Evangelicalism paved the road for Evangelicals’ support for Trump. As a candidate, he projected an aura of personal strength, ceaseless success, patriotism, and fortitude — ignoring how contradictory this narrative was with his inconsistent record as a businessman and his privileged background. Moreover, he adopted the rhetoric of an anti-intellectual, anti-establishment, nationalistic, strongman who had worked his way to the top. These characteristics do not put him at odds with Evangelicalism; they situate him comfortably within its American history.

It should also be noted that Evangelicals overwhelmingly supported Ronald Reagan, a divorced man and infrequent church attendee, over Jimmy Carter, a Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher. In doing so they embraced Reaganomics and a free-market economic agenda, among other tenets now considered synonymous with Evangelical politics.

The overwhelming white Evangelical support for Trump on election day could not have been possible without a history that had been so sympathetic and laudatory of strong, wealthy figures like him. In an election where the economy was cited as a chief concern among evangelical voters, it seems reasonable that they would be receptive to a candidate that appealed to entrepreneurial sensibilities.

Historical instances of this affinity for business characters, however, extend far beyond this; since the invention of the radio and television, media outlets have provided a platform for “Christian figures” to engage in elaborate exploitation of America’s most credulous and desperate. Evangelical entrepreneurs, who would later be referred to as televangelists, put themselves out on such platforms under the purported aim of teaching the gospel.

A particularly infamous example of this can be found in the case of Jerry Falwell, the televangelist and founder of Liberty University. He spewed vicious rhetoric about gay marriage and contraception, while claiming that the US deserved the 9/11 attacks because of its endorsement of homosexuality.

One key element of televangelist mantra was carefully crafted instructions on how to increase personal wealth; unsurprisingly, this often concluded with the advice to give money to the televangelists themselves. Despite what may seem like a disgraceful perversion of the Christian faith, televangelists like Mike Murdock are, for many devout Evangelicals, a source of “hallowed” advice on how to become rich.

In other religious denominations in the US, we do not see the transposition of faith into media platforms and popular advice about making money. The emergence of the televangelists indicates a specific market within Evangelicalism for capitalistic exhortations and commentary. Whether this is a consequence primarily of the socio-economic conditions many white Evangelicals find themselves in or a product of the faith itself, this modern cultural phenomenon is consistent with the frequent entanglement between entrepreneurial spirits and Evangelicalism.

In this regard, Donald Trump’s campaign expelled a similar rhetoric to the televangelists. Just as the televangelists offered outlandish instructions on how to increase one’s wealth and achieve a more prosperous life, Trump campaigned under the promise to “Make America Great Again.” In doing so, he appealed to the very same capitalist sensibilities that helped spur the rise of televangelism. As Ellen Wayland-Smith puts it in an article for The New Republic, “Trump mesmerizes audiences with his claim that everything he touches turns to gold. He promises salvation through business savvy and survival-of-the-fittest battles to the death…”

Of course, some white Evangelicals expressed mixed feelings about Donald Trump. This is clear in the dialogue occurring at Liberty University, one of the world’s largest Evangelical colleges, where students are firmly divided about Trump. And yet, as Politico details, Liberty University leaders still resolutely support Trump as a “Dream President,” and the backlash to Trump has emerged almost exclusively within an “underground” movement at the institution. To the extent that white Evangelicals have offered a tangible pushback against Trump, it’s been almost entirely consolidated to the quiet, relatively inconsequential groans of more incredulous young people.

White Evangelicals were not deterred by Trump’s apparent impiety. On the contrary, white Evangelicals were allured by his rhetoric and campaign promises. Although it would be misguided to claim that Trump embodied Evangelical principles, the commonly espoused notion that he was the antithesis of Evangelicalism seems similarly erroneous. Trump was both an antagonist of the pulpit and a patron of it. This odd relationship is a natural product of a religious history that has so often seen the interweaving of the businessman and the preacher man; the interdependency of the dollar and cross.