Derek West Harris was an easygoing, chatty barber who went by D-Nice. In 2009, Harris was arrested for failing to register his new car and had to pay $700 worth of traffic tickets. More unusual was that Harris was also sent to a New Jersey halfway house called Delaney Hall. Originally built to rehabilitate 1,200 inmates convicted of minor offenses, Delaney Hall’s purpose was to provide its residents with counseling, so as to prevent recidivism. But when Harris arrived, the halfway house also contained several criminals convicted of violent crimes. Two days into his stay, three inmates, who had been previously been suspended from the halfway house for disruptions, entered Harris’ unlocked room. After demanding that he empty his pockets, one of the attackers pounded on Harris’ chest while the others rifled through his belongings. Vincent Caputo, an inmate in a nearby room, would later testify that he “heard fighting, wrestling, yelling, screaming [and a] guy yelling for help.” Yet none of Delaney Hall’s workers responded to the sounds, and, after choking for a few minutes, Harris died on the floor of his room. Harris’ three attackers fled the scene with their loot — the $3 they had found in Harris’ pockets.

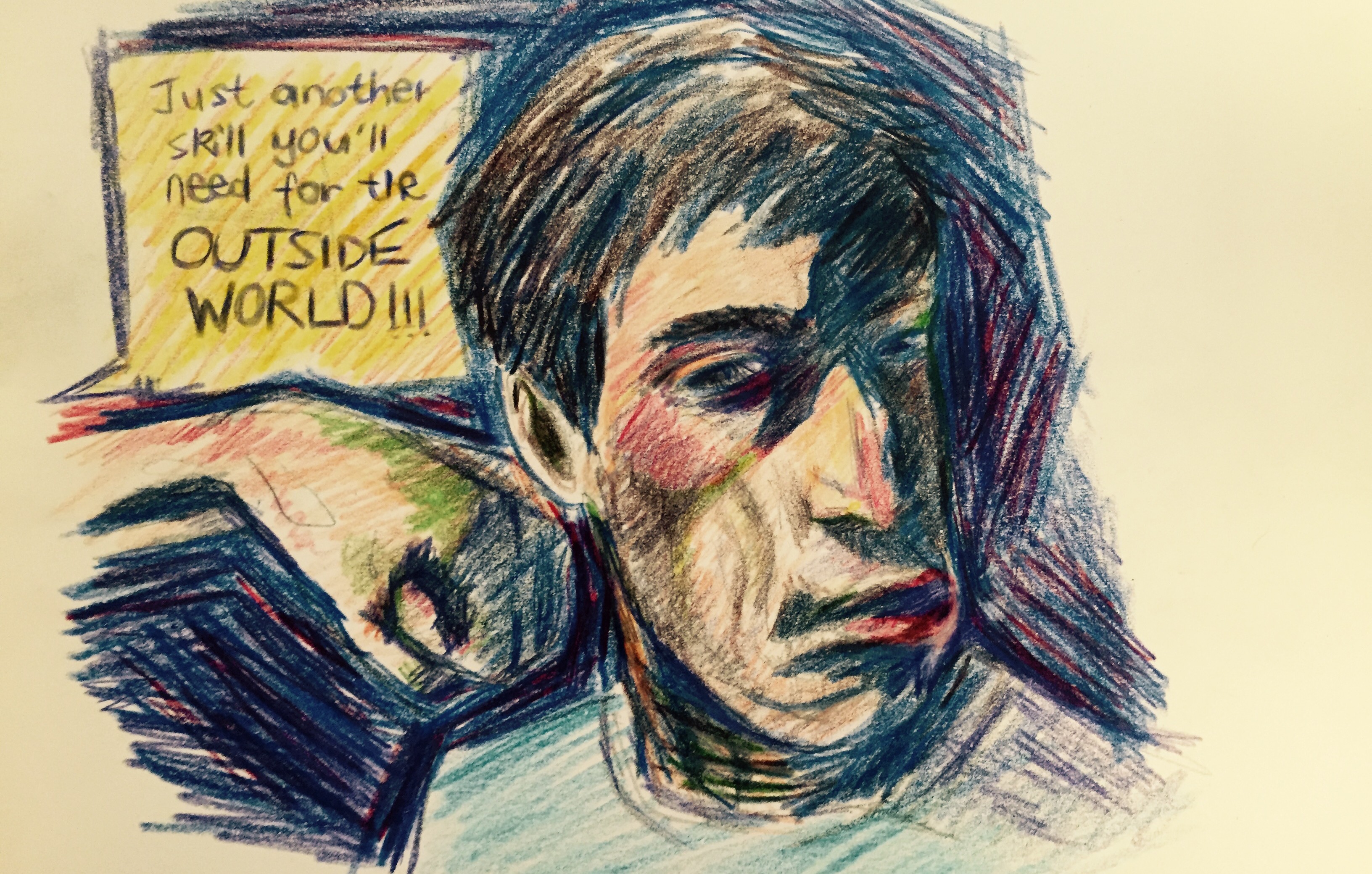

Halfway houses are not supposed to be like this, but problematic regulations and attempts to make up for budget shortfalls have undermined their original purpose. Halfway houses were envisioned as places where nonviolent inmates could spend the last part of their sentences gaining the skills they needed to be successful on the outside. By focusing on helping soon-to-be ex-convicts find stable housing and employment, the institutions were meant to be primarily rehabilitative instead of punitive — a way to reduce recidivism while simultaneously lowering costs. As such, halfway houses became a popular policy solution for corrections departments around the country. Yet, as the policy gained momentum, halfway houses increasingly became unregulated warehouses where prisoners could be dumped at reduced costs.

Today, most halfway houses are privately owned and run. They range from small residential buildings housing a handful of residents to large complexes with several hundred beds. While some contract with state and federal governments, others market their services directly to those exiting the system. Halfway houses are often paid a flat fee for every bed they fill; in exchange, they provide career counseling, rehabilitation programs and assistance finding housing to their residents.

The regulations for these institutions vary across the country. Some states, like New Jersey, only allow nonprofit organizations to bid for contracts to run the houses. In other states, the requirements are laughably fluid or, as in Florida, nonexistent. Lax standards can be detrimental to the intended beneficiaries of these facilities because they allow exploitation of both the system and the people within it. In one particularly outrageous incident, a Floridian halfway house that touted itself as a “sober living” facility actually sent its recovering alcoholic residents to sell beer at Raymond James Stadium in order to make money for the house. Another halfway house in St. Petersburg, Florida — dubbed the House of Hope — was run by Patrick Jay Banks, a former felon who spent eight years in prison for robbery and forgery. Banks used the institution as a moneymaking scheme, falsely submitting reimbursements to take advantage of the Bush-era Access to Recovery program, which gave states funds to increase access to substance abuse programs and recovery support services. At one point, Banks billed for services provided to 50 residents, even though his tiny house barely provided services to the 10 residents who were actually there. He collected over $110,000 from the federal government before he was permanently barred from participating in the program in 2007. Yet just a few years later, Banks opened another house, and in 2012, he received $55,000 in federal funds for the provision of rehabilitation services. Unfortunately, Banks is hardly an exception in this dangerously unregulated industry.

Even states with supposedly stringent regulations have let egregious violations slip through the cracks. Despite New Jersey’s nonprofit rule, which was created to undercut the profit motive of these institutions, some halfway houses have found methods of purposefully circumventing the state’s rule. One of New Jersey’s largest halfway house conglomerates, Community education, is really a for-profit company that can only contract with the state by funneling money through its shell nonprofit organization, Education and Health Centers of America. This nonprofit provides few services beyond transferring the funds it receives from the New Jersey government to Community Education. The organization has only 10 employees, yet it paid the Community Education CEO a salary of $351,346 in 2011. As Mercer County Assemblywoman Bonnie Watson Coleman put it: “This…smells to high heaven.” In light of such cases, halfway house regulations appear feeble, if not downright toothless.

In theory, however, halfway houses might still seem more efficient than the current prison system. Because the rehabilitative services that halfway houses provide are supposed to reduce recidivism, housing an inmate in a halfway house saves the government money by reducing the chances that the offender will break the law again and be imprisoned. The fiscal impact of the organizations is positive in a more direct sense as well; housing inmates in halfway houses is markedly cheaper than incarcerating them in prisons. While the immediate savings are generally small — for example, New Jersey pays halfway houses between $60 and $75 per day per bed versus $125 to $150 a day to house each prison inmate — the cumulative savings can make a sizable difference to many cash-strapped federal and state budgets.

Halfway houses’ cost effectiveness may have ultimately caused their own decline. When the recession hit in 2008, the tightening of corrections budgets precipitated an increased reliance on halfway houses. It was not an inconsequential shift. As was the case at Delaney Hill, halfway houses no longer serve as places for the rehabilitation of minor offenders — but also for those guilty of more dangerous crimes. This occurs primarily to save the state money. Those more violent criminals are people whom the halfway house system was not set up to handle, and the results of their influx into these institutions have been disastrous.

Violence and drug use run rampant in halfway houses today. A random, externally administered drug test in a New Jersey facility found that 73 percent of the residents tested positive for drug use. Following the results, the prisoners who tested positive were removed from the facility, but no further action was taken to curb the problem. Brian M. Hughes, a Mercer County executive, believed “staff were making drugs available to the population.” And although rampant drug use is certainly a stain on halfway houses, it is far from their biggest problem. When the New Jersey State Commission of Investigation examined the presence of gangs in the state’s correctional facilities in 2009, it found that those most plagued by gang activity were not prisons but halfway houses. The same study found that gangs completely controlled the phone system in one New Jersey halfway house.

Halfway houses are clearly inundated by a host of problems, yet they are ill-equipped to handle them or even their own basic functions. Because they focus on keeping costs down, halfway houses are frequently understaffed by poorly trained employees unable to provide sufficient rehabilitative and counseling services. In one halfway house, the ratio of inmates to guards on night duty was alleged to be as high as 200 to 1. As a result of understaffing, supervisors would forge patient records and facility reports. “When we had to give a report,” Cynthia Taylor, a former counselor at the Albert M. “Bo” Robinson halfway house in Trenton, NJ, said, “We would look at what was said for the last group and cut and paste.”

This system of entrenched neglect creates situations in which inmates face abuse by other prisoners or staff members but lack any real ability to file charges or make changes. Vanessa Falcone’s nightmare began with her assignment to the cleaning crew at Bo Robinson. One night Falcone’s supervisory janitor ordered her into a supply closet. “He took his pants off and grabbed my hair and pushed me down,” Falcone said in an interview with the New York Times. “That started a few weeks of basically hell.” When she finally mustered up the courage to tell her guard that she was being sexually assaulted, the halfway house dismissed the janitor and transferred Falcone to a different facility. But charges were never filed. As she describes it: “They shipped me off to another place like it never happened.”

It is no surprise, then, that some residents of halfway houses will take any chance they can get to escape — especially since jumping ship is so easy. All of the facilities are low-security because they are designed to house offenders guilty only of minor crimes. But with the increasing numbers of inmates sent through halfway houses and the subsequent surge in violent offenders, the already limited security in these facilities is becoming less effective. Most of the time, residents escape when they are out on work-lease or on a visit to their homes. But there are also worrying reports of residents escaping as easily as walking out of their compound or climbing a fence.

Generally speaking, there are no serious consequences for those residents who run away; most are never even charged for escaping. However, escapees pose a serious risk for society at large. Residents who run away avoid the mechanisms of parole that are designed to allow the state to keep an eye on past offenders as they reenter the community. The consequences can be more devastating than expected, as is evident in the case of David Goodell. After spending more than a year behind bars for pinning a former girlfriend to the ground and threatening to kill her, Goodell was transferred to a halfway house in Newark, NJ. One night, after pretending to have a seizure, Goodell was admitted to a hospital nearby, accompanied by a halfway house worker who had no authority to restrain him. Shortly after arriving at the hospital, Goodell escaped and headed straight to the suburbs, trying to contact a different ex-girlfriend, Viviana Tulli. He managed to persuade Tulli to meet him, and, later that night, strangled her to death in his car.

Goodell’s example is certainly an extreme one, but it is nevertheless a symbol of a system riddled with corruption, violence and lawlessness — one that is in dire need of reform. With 30,000 inmates passing through the federal halfway house system each year — and even more passing through the state systems — it’s crucial that conditions in these facilities be improved. The goal of the halfway house is well intentioned: to better prepare those convicted of crimes for their lives after prison. Yet, as of now, these facilities do just the opposite.

A study conducted by the Pennsylvania Corrections Department concluded that halfway houses have limited, if any, effect on reducing recidivism. The study found that 67 percent of inmates sent to halfway houses were rearrested or sent back to prison within three years, compared with 60 percent of inmates who were released directly onto the streets. It comes as no surprise, then, that in 2013 Pennsylvania Corrections Secretary John Wetzel went so far as to call his state’s halfway house system “an abject failure.”

Although the problems that plague halfway houses are well known by politicians and policymakers, change is hard to come by. Bills aimed at reforming the system are voted down year after year in states like Florida and New Jersey, despite repeated evidence of their systems’ failings. Part of the lack of political will is due to the fact that the populations most hurt by halfway houses are also the ones that are chronically underserved. Like the rest of the prison population, those housed in halfway houses tend to be minorities of low socioeconomic status, many of whom have mental illnesses or substance abuse problems. Moreover, politicians have financial incentives to maintain the status quo, since halfway houses are an important cost-saving measure when it comes to corrections.

Even in states that have undertaken efforts to improve their corrections systems, politicians have insisted on maintaining as much of the savings usually produced by halfway houses as possible. For example, Pennsylvania recently linked its payment of halfway house operators to their residents’ recidivism rates. Now the state’s halfway houses are scored on their provision of services, security, operations and employment, as well as on their recidivism rates. If the houses fail to remain in good standing, they can be fined, paid less or have their contract with the state terminated. Highlighted by a Rutgers University study as a successful reform effort, Pennsylvania’s laws are just one way that states try to improve their halfway houses.

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) also recently took a step towards reform by mandating that all federal halfway houses deliver standardized mental health and substance abuse counseling and that they hire only those with prescribed qualifications to do it. Attorney General Eric Holder said of the reforms: “This will ensure consistency and continuity of care between federal prisons and community-based facilities. And it will enhance the programs that help prisoners overcome their past struggles, get on the right path and stay out of our criminal justice system.” However, the mandate only applies to the federal system and still does not tackle many of the issues, such as security or overcrowding, that continue to plague halfway houses across the country.

Both the DOJ and Pennsylvania’s reform efforts are promising in that they attempt to address the root of the problem: halfway houses’ failure to meaningfully provide the services that they are intended to supply. Unsurprisingly, a study of Ohio’s halfway houses found that the biggest predictor of each house’s success is its ability to deliver the treatment, counseling and other services initially promised to residents. The study concluded that when these services were effectively provided, halfway houses did have positive effects on the recidivism rates and earnings of their residents. With this in mind, it is clear that reforms must continue to push for halfway houses that effectively accomplish their job of providing robust support to ex-convicts.

But the road to reform is long. Today, halfway houses lack any real contribution to either the judicial system or civil society — the two realms that halfway houses are intended to bridge. If that is to change, politicians can no longer view these houses as short-term cost-cutting mechanisms. Instead, they will need to keep the long-term goal of reducing recidivism close. Until states and the federal government seriously undertake efforts to improve their corrections systems, halfway houses will remain a half-measure.

Art by Michelle Ng.