Pavlov’s process of classical conditioning is pretty simple: If he rang a bell every time he gave his dog a treat, the dog would begin to salivate at just the sound of the bell. Now, imagine that instead of a dog, it is everyone aged 15–30. Instead of ringing a bell, it is tapping a heart-shaped button on an Instagram story. And instead of a treat, it is sex. The routinization of romance on digital interfaces has done away with the ambiguities of in-person flirting. We can now receive a ‘like’ on our Instagram story and suspect that that person is into us. The art of relationship building that comes from learning someone’s personality, tics, and communication style is disappearing in our inept search for clarity via conditioned digital behavior.

This conditioning of digital gestures has generated a new set of romantic rituals: liking Instagram stories or dating app profiles to show interest in someone; texting, commenting on their posts, and sending them reels once you start hooking up; posting with them and deleting dating apps once things are serious. These behaviors have become so standardized among young people that they serve as widely understood signals of intimacy and celebrations of different levels of commitment.

Standardizing our signifiers of romantic interest and relationship status has not eliminated as much ambiguity as we might think. True, it now seems easier to tell if someone likes us, but how many other guys is he matching with? Does her “story-like” mean she wants to date or just have sex? It seems obvious when some people are hooking up and some people are dating. But he also commented the same emojis on her post, although he claims they are just friends… Is he hooking up with both of us? She did not post for ‘National Boyfriend Day’ this year—does that mean I can ask her out?

Opening up new modes of interaction and communication also opens up new avenues of confusion. We are grappling with the illusion of a clear and standardized digital semiotic system. What liking a post means to one person might mean something else to another, despite our best attempts to assimilate everyone into a universal romance language.

We cannot reconstruct the Tower of Babel—a sanctuary where everyone speaks the same language—because flaws in human communication are unavoidable. It is impossible to express our complex internal thoughts and feelings perfectly. It is impossible to understand someone else fully. It is even more impossible to attempt either of these goals using abstracted buttons on screens rather than complex human languages, body language, pheromones, touch, and other facets of in-person human communication.

Abstracted indicators of interest not only oversimplify human interaction but also condition users to read into the smallest of interactions. The hyper-analysis of micro-interactions online, such as ‘story-likes,’ has led to a dating landscape that traces “connections” across so many incremental stages of commitment that it is difficult to tell what is allowed and when. The complex and ever-changing rules of modern dating, coupled with the oversimplified nature of the digital language tools at our disposal, are bad news for any of our parents hoping to see a wedding or grandchildren anytime soon.

Beyond modes of communication, shorter attention spans may be undermining our ability to foster monogamous relationships. We are less capable of deep introspection; when we sense tension in a relationship, we are more likely to run away from the discomfort and self-soothe by swiping on Tinder or posting a thirst trap to see who else likes it. Instant gratification has conditioned us to expect constant entertainment and dopamine release: If a relationship starts to get tough or boring, we are psychologically conditioned to end it and find pleasure elsewhere. We cultivate “rosters” of romantic interests to turn to at the slightest inconvenience as a defense mechanism against sitting in difficult emotions. We are becoming worse at thinking through our own problems and sticking around through someone else’s. This phenomenon is stunting personal development: How are we meant to emotionally mature into adulthood if we run away from our problems, drowning our anxiety in instant gratification?

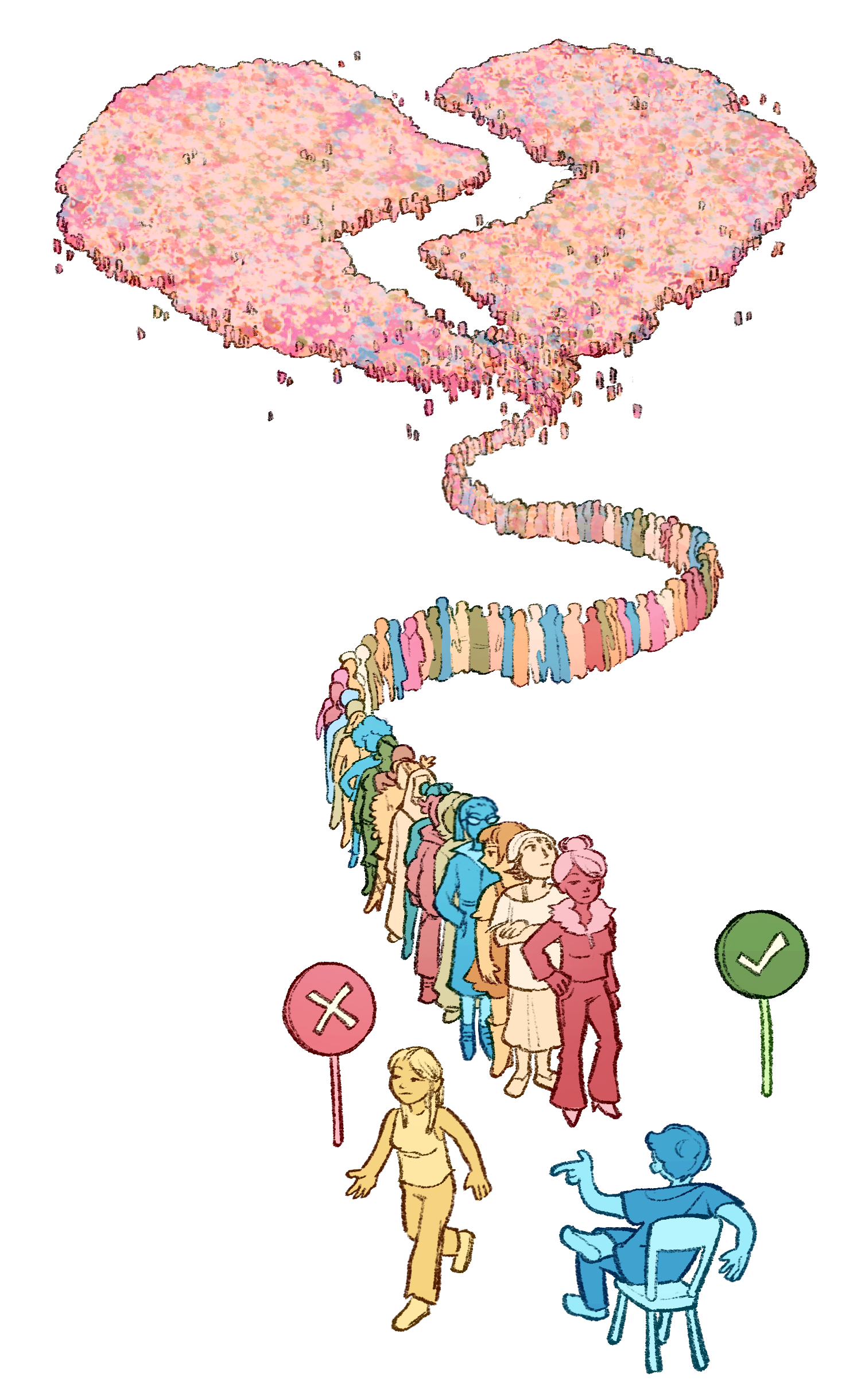

As a consolation, at least we can expect that young people are gaining more sexual experience than previous generations, right? Wrong. Studies show young people today are having less sex than previous generations. “Rosters” of Tinder and Hinge matches and loyal “story-likers” not only disincentivize commitment to serious relationships; they also disincentivize doing anything romantic. Balancing multiple options can overwhelm and paralyze us from acting on anyone. Having multiple lines of communication open at once means no one ends up texting back in time to actually coordinate a date. And, the swarm of hot, algorithm-picked “micro-celebrities” on our feeds increases the illusion of options while also potentially deluding us into setting expectations for partners that are beyond reason, feeding a rejection mindset that restricts us from ever finding a romantic interest outside the internet.

For some people, digital romance is enough. Texting people on dating apps, getting likes on their posts, and knowing that there are tons of hot people out there is gratifying enough that they do not pursue relationships or sex. However, as much as the internet may satiate some people’s sexual desires, the ongoing mental health crisis points to another cause of less sex among young people: Despite hyper-sexuality online, more young people are anxious and depressed than ever before. Some people might have a “roster” but are too anxious to do anything about it offline. Other people may have had such bad experiences with digital romance that they are swearing off relationships and sex altogether. The mental health crisis and increased isolation will only further preclude Gen Z from finding love.

More than anything, streamlining and “simplifying” communication sacrifices the bedrock of intimacy and developing chemistry—the excitement and intrigue inherent to real-world interactions. Going up to the hot guy at the bar in a burst of spontaneity, the serendipity of asking out the pretty girl on the train, not knowing if that person wants to get coffee as a date or just platonically… In the real world, there are no buttons, and we cannot swipe. The only way to find out if someone can be a connection is to engage in a real, face-to-face conversation that, while also ambiguous in some ways, is more informative than we give it credit for. Body language, tone, eye contact, and pheromones all help foster an understanding of intimacy that is inaccessible online. Going through the motions of preset micro-stages of intimacy is inhuman. We should not classically condition ourselves into relationships with the right ding of a notification bell.