How much does it cost to win a gubernatorial election? Or to kick out an incumbent Republican Senator? How much does it cost to save the environment?

Answers to these questions may become clearer in coming years. The 2010 Supreme Court Citizens United decision that licensed unions, businesses, and wealthy individuals to pour unlimited money into political elections via super PACs has mutated the political landscape by allowing an unprecedented amount of money into American elections. Super PACs facilitated a surge in campaign spending in the 2010 midterms, the 2012 presidential election and already the 2014 elections. In the wake of Citizens United, the 2012 presidential election proved the most expensive in American history. President Obama and Mitt Romney raised over $1 billion each; Super PACs alone contributed $92 million to Obama’s coffers and $225 million to Romney.

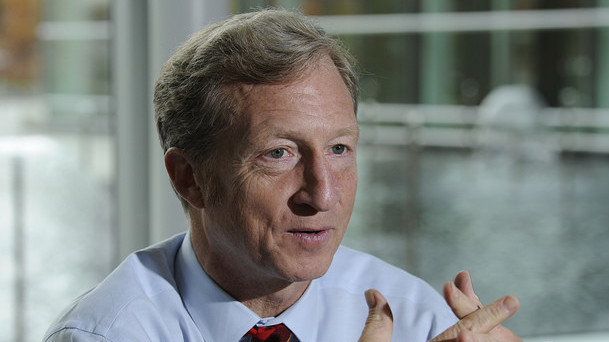

In conjunction with the unprecedented amount of money circulating in American elections, the Citizens United decision empowered at a new level a controversial breed of political player: the billionaire. The New York Times on Monday reported on Tom Steyer, a retired hedge fund investor currently valued at over $1.4 billion, and his ambitions for his pro environment Super PAC, NextGen. Steyer aims to raise $100 million for the disposal of his political action committee: $50 million of his own funds and another $50 million potentially raised from outside donors. NextGen will spend the millions on attack ads targeting mainly Republican politicians around the country in an effort to displace them with environmentally friendly lawmakers.

Mary Landrieu is the lone Democrat on the docket of potential targets for NextGen, but Steyer’s political activity is party neutral. “You need to be agnostic as to party. If I find someone who has the right position on climate change, do I care if he owns six guns? Not at all,” said David Topper, a private investor Steyer courted for donations.

As PublicIntegrity.org reports, Steyer’s work is consistent with the “latest iteration” of Super PACs, first comers being “shadow party committees,” and the second being candidate focused PACs. Now, “single issue vanity Super PACs,” or groups “backed by a single, wealthy donor focusing on an issue of national importance,” are coming on the political scene in full force. Michael Bloomberg’s post-mayoral career in politics is being called “The NRA’s End.” Bloomberg’s been a long time proponent of gun control, he founded Mayors Against Illegal Guns in 2006. Now Bloomberg is dedicating his political clout and enormous wealth to the efforts of his Super PAC, Independence USA. As of 2013, Bloomberg remained the sole donor to the Super PAC which has spent millions targeting elections across the country.

Such PACs operate outside party agendas and at times frustrate them. Additionally, the magnitude of political power wielded by an individual on the basis of wealth is a troubling prospect for the future of America’s democratic process. But single issue, independent groups create a new dimension in political play with potential upsides. PACs ensure that parties don’t have exclusive control over the national agenda. The gun control issue provides an ideal example: thought congressional legislative efforts fail decidedly, the opportunity for reform has not disappeared, though Party attention for the issue has.