In the last few decades, the government of the People’s Republic of China has sought to grow its influence in not only the Indo-China region, but beyond the nations in its proximity. The West accuses China of practicing modern-day colonialism—neocolonialism—in Africa, and more dominantly, in the southwestern country of Angola. In light of this, this article hopes to unpack a contrasting perspective: Is Sino-Angolan trade truly neocolonialism if there is little domestic interference by China? Liberal thinkers suggest the affirmative, in part because it is far too easy to picture a small African country as being easily influenced—malleable. On the other hand, a narrative of China controlling “innocent” African governments is in the best interest of the United States and Europe, for whom curbing Chinese hegemony in the Global South sustains their own great power status. In this light, the label of neocolonialism is a simplistic, distorted take on the decades-long relationship between China and Angola.

In 1975, the newly independent country of Angola plunged into a civil war to establish the ruling party of its first, official government. The Angolan Civil War between the socialist urban People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the capitalist National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), and the northern guerillas, the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), was sustained by external aid from world powers to each rebel group. At the height of the civil war, the Chinese government funded the FNLA and UNITA—the bitter rivals of the MPLA. Yet, even as the unsupported MPLA became the leading party in the country, the Sino-Angolan relationship was founded. This birth was signaled by the creation of a Joint Economic and Trade Commission in October of 1988. Still, the economic and political ties between China and Angola moved to unforeseeable heights in the early 21st century, creditable to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The Belt and Road Initiative is an infrastructure development project launched by the Chinese government in hopes of expanding East Asian countries’ economic and political influence around the world. In the context of Africa, Angola has emerged as the second main destination of Chinese investment, and it was in 2004 that China’s first infrastructural line of credit was given to Angola in exchange for production rights in Angola’s oil blocks.

In this 2004 trade deal, Sinopec, a Chinese oil and gas company, gained control of Oil Blocks 3/05 and 3/05A. In return, the Angolan government received a $2 billion line of credit through China’s Eximbank. This deal is particularly important, as Angola’s state-owned petroleum and natural gas company, Sonangol, discontinued French energy company Total’s ownership of Blocks 3/05 and 3/05A, and gave control of the oil blocks to Sinopec. On the surface, there seems to be an attractiveness to Chinese trade that the West is unable to recreate. As Dezan Shira & Associates puts it, “China’s loans are an attractive alternative [for Angola] to those from international institutions.” It is common wisdom that this is on account of Chinese loans having no democracy-promoting strings attached, unlike those from liberal institutions and Great Powers. Moreover, it may be their greatest virtue.

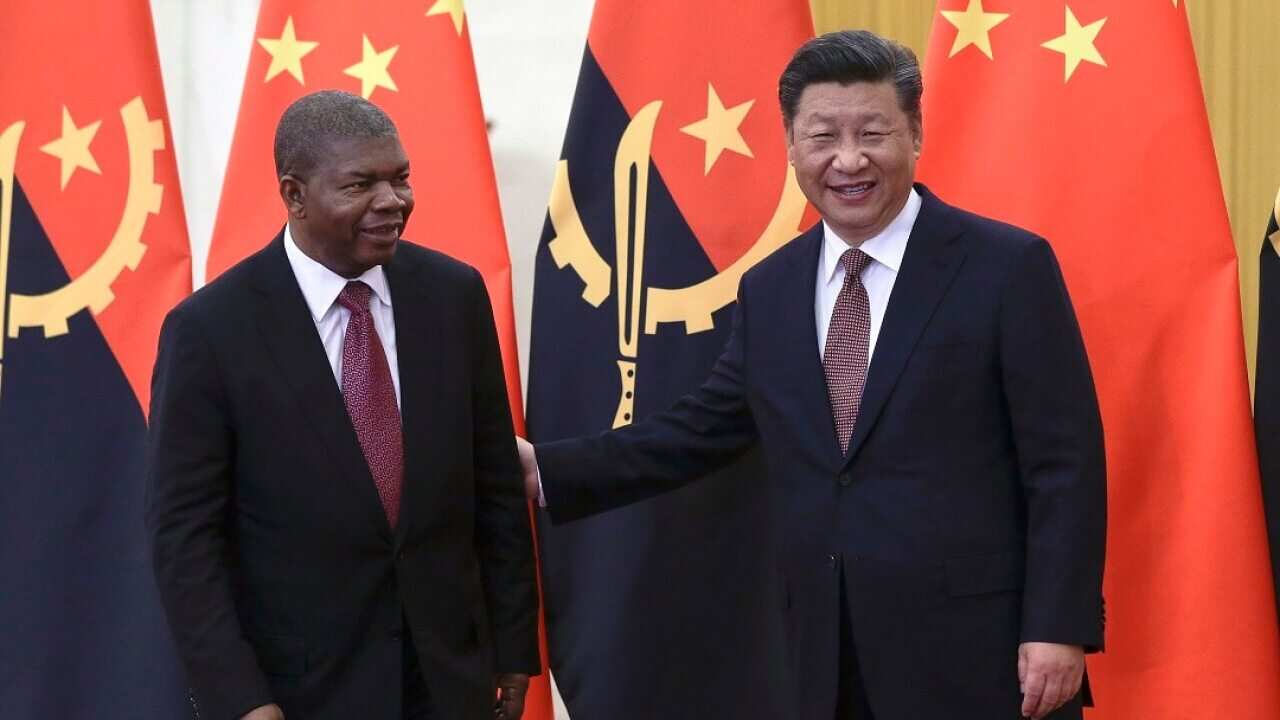

In analyzing how Chinese trade deals interfere politically and economically in Angola, there is strong evidence that proves Beijing’s non-interference approach with regard to Angola’s domestic politics. For example, in 2006 during Premier Wen Jiabao’s visit to the capital of Luanda, the Chinese leader reinforced that Sino-Angolan relations have no “political preconditions.” And as seen with China’s establishment of diplomatic relations with the unsupported MPLA during the Civil War, China is clearly quite politically adaptable in regards to Angolan politics—a characteristic in stark contrast with neocolonialism.

Furthermore, in regards to economic interference, China’s economic influence in Angola is owing to the longstanding Sino-Angolan relationship. The large influx of Chinese exports, valued at $1.75 billion in 2020, has contributed to Angola’s towering $73 billion debt. Of this total, Chinese money is responsible for 40 percent of Angola’s external debt. For this reason, Western scholars, like Jean-Marc F. Blanchard, accuse Beijing’s “debt-trap diplomacy” of “[bearing] close resemblance to the European colonial powers’ relations with African [countries in the 19th and 20th century].” In essence, the West is crying neocolonialism. But, dare anything in the international system be that simple?

To acknowledge the enormous debt owed by Angola to China is not synonymous with accepting the debt-trapping accusations of the West. This liberal view fails to consider the wider scope of the Angolan economy. The perception of risk, six years of economic crisis, and the dollar-denominated output crash have all contributed to the country’s debt to China. Yet, it is specifically because of the Eximbank’s loans that Angola is able to begin industrializing its economy to repay its debt to world powers like China and Great Britain—the second largest holder of Angolan debt. An example of this industrialization is the $28 million from China used to construct the “Centro Integrado de Formação Tecnológica’” in the Angolan province of Huambo, which will have the capacity to train 1,200 pupils. Evidently, Chinese loans present a direct opportunity to advance the Angolan economy. But, it is in the hands of the government to build innovation centers, invest in the youth, and maximize the nation’s vast economic potential. The country has the capability to “become the fourth largest economy in Africa by 2050.” And only it can stop itself.

Ultimately, in the words of Deborah Schwartz at Johns Hopkins University and Meg McFarlan at Harvard Business School, claims of debt-trapping “cast China as the conniving creditor” and countries like Angola as its victims. In a liberal hegemonic world, the Great Powers are the known swindlers. Although seemingly absurd, it is possible that Angola’s debt is not a Chinese issue, but rather simply a pressing domestic affair for Angola to address. And, through giving Angola the political and economic liberty to develop its own sustainable industries, Beijing is giving her the freedom to do so.

The non-interference approach adopted by China challenges the principle that Great Powers have a responsibility to protect. Intervening in foreign societies and proceeding to promote particular ideals is at the backbone of liberalism. And whilst China has engaged in this principle, as seen in Sri Lanka and Djibouti, the Sino-Angolan relationship is hardly an example of such.

With that, the question is posed once again: Is Sino-Angolan trade truly neocolonialism if there is little domestic interference by China? As aforementioned, liberal thinkers suggest the affirmative, yet that is a frail perspective on the Sino-Angolan trade relationship. The nature of this bilateral partnership is one of mutual advantages. As the late Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos affirmed once, “China needs natural resources and Angola needs to develop its economy. That is why the two countries have engaged in constructive cooperation.” In conclusion, Sino-Angolan trade is not neocolonialism. Chinese non-interference allows Angola’s economic and political development to be made on its own terms, on its own turf.