Do American politicians see themselves as American Jews or Jewish Americans? That question, and the cultural stigmas behind it, presents these two competing identities as mutually exclusive: one must be sacrificed to cater to the other. Jewish-American politicians’ efforts to maintain some sort of balance, while creating “political packages” attractive to voters, highlight the challenging decision of how much Judaism should factor into that political package.

It is hard to compare how Jewish politicians choose to present their Judaism compared to how members who identify with different religions present their faiths. Protestant politicians, who make up the majority of Congress, do not have a defined stereotype to fit or contradict because Protestantism is the American norm. However, Catholics, who make up the next largest religious demographic in Congress, have a bit more defense to play. Catholic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy had to convince the country that his loyalty would lie with the United States before the Vatican. Even in the last vice presidential debate between Catholic vice presidential contenders Joe Biden and Paul Ryan, Catholicism was directly addressed in a question about abortion.

For many Jewish politicians, however, religious identity affects more than just prescribed values. To many, Judaism is a lot more than a faith—it is a culture, a religion and a people. Just like any (quasi) ethnic minority, Jews have been ascribed a number stereotypes: intelligence, greed, financial prowess, and neuroticism. It can be more or less advantageous for politicians to play into that range of stereotypes to varying degrees depending on their constituencies.

Eric Cantor was the only Jewish Republican in Congress when he left in June. Although Cantor made no secret of his Judaism, he was not stereotypically Jewish. He speaks, for instance, with a Virginian Southern drawl and not the stereotypical Allen-esque inflection that has come to stereotype the Jewish voice. He has not attended a single Jewish event at the White House during President Obama’s two terms, although he was invited to all of them. However, while he does not play into the common trope of the cultural Jew, he has made no attempt to downplay his religion, either. In fact, since becoming the only Republican Jew in Congress in 2006, Cantor has dived into Jewish scholarship, even taking private lessons with rabbis. This is a strategic move for a politician appealing to Republicans, who tend to place a greater value on religion. While the Republican Party is comprised of a large Christian majority, Cantor was able to relate to his voting base as a man of the Judeo-Christian God and prayer. While most of his voters would not necessarily declare Cantor a “mensch,” they can still relate to his religious beliefs.

Jewish politicians running for office in areas with a denser Jewish population, however, play a much different game. Michael Bloomberg, former New York City mayor, presented as much more stereotypically Jewish. Bloomberg has been known to toss around some Yiddish, like in 2009 when he declared potential state senate actions as “meshugenah” on the radio. In the same year, he also circulated a help-wanted flier for field workers to rally the vote in Brooklyn and Queens that expressed a preference that they be proficient in Yiddish or Hebrew.

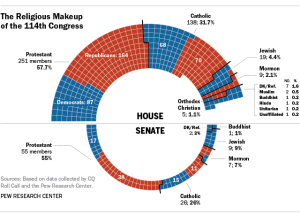

Geographical and religious demographics have far-reaching effects on Congress. The newly sworn 114th Congress includes twenty-eight Jews, which represents 5.2 percent of congressional members. While this number is larger than the Jewish share of the adult American population, which is about 2.2 percent, the amount of Jews in Congress has hit a decline. The 113th Congress included thirty-three Jews, the 112th had thirty-nine and the 111th had forty-five. In fact, no American Congress has seen so few Jews since 1971, when the 91st Congress contained nineteen Jewish senators and representatives.

The most recent drop in the number of Jews in Congress can probably be attributed to its Republican takeover. Jews vote overwhelmingly Democratic, and of the thirty-three Jews in the 113th Congress, thirty-one were Democrats. There was only one Republican Jew in this congress—Eric Cantor—and one Independent—Bernie Sanders. While about 70 percent of American Jews identify as Democrats, about 94 percent of Jewish representation in this Congress was Democratic. Since the House lost Democrats and gained Republicans in the 2014 midterm elections, the decrease in Jewish representatives is more easily explained.

Before the most recent election, it is possible that the pattern of decline could have been caused by general population shifts. Due to population changes in the past few years, Northeastern states like New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania have lost seats in Congress while some Southern and Midwestern states such as Arizona, Utah and South Carolina have gained them. Since the states with the highest concentration of Jews are also the ones that have been losing seats, it only makes sense that the number of Jewish representatives in Congress is declining.

The correlation between party affiliation and religion can create for some interesting dynamics in Congress, especially for the Democratic Party, of which Jews constitute 11.5 percent. Accordingly, issues especially important to Jewish Americans affect the Democratic Party much more significantly than the Republican Party. This caused a riff when Speaker of the House John Boehner invited Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to speak to Congress in January as a snub to President Obama. While many Democrats plan to skip the address out of solidarity with the President, over half of the Jewish representatives surveyed by The Hill reported plans to attend the address. So far, only two Jewish congressmen report plans to skip it. However, prioritizing certain Jewish values by no means prevents politicians from prioritizing the well-being of their country and political parties, as well. Soon after Netanyahu was invited, six prominent Jewish House Democrats met with Israeli ambassador Ron Dermer to address concerns about how the issue was handled.

Religious groups other than the Protestant majority routinely have their political stances and policy interests questioned in relation to their religious beliefs. However, because Israel, and, by relation, Judaism, has become a growing political issue, Jewish politicians have faced greater scrutiny when it comes to their claims of balancing church and state. Recognizing that cultural and political shift is essential in evaluating Jewish-American politicians’ “political packages” – especially during an election season.