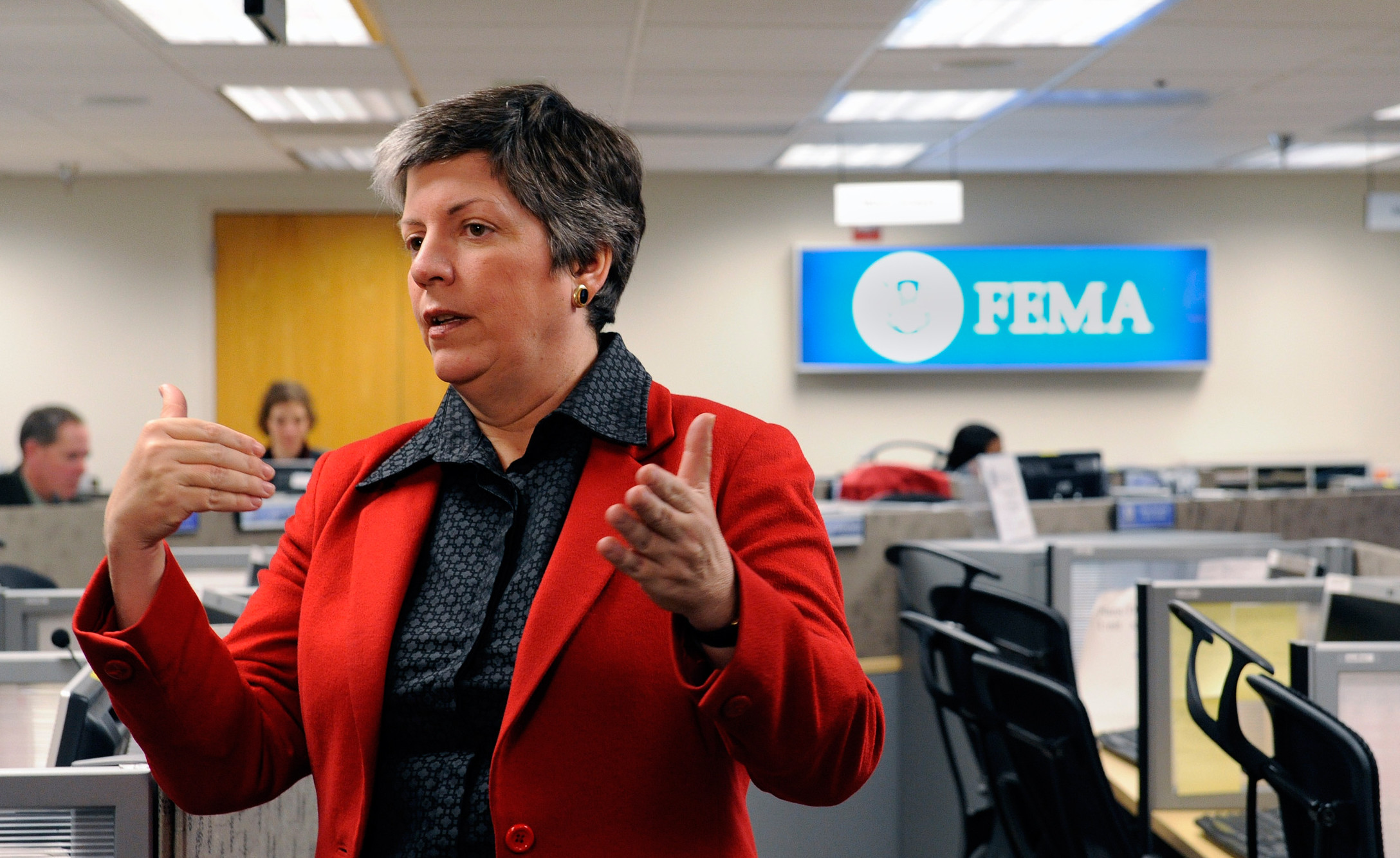

While it was an issue that originally flared up some months ago, the controversy surrounding the appointment of Janet Napolitano, ex-Secretary of Homeland Security and Governor of Arizona, as the new president of the public University of California (UC) system has resurfaced in the news of late. The initial antagonism had manifested itself in a floated student government proposition to condemn the confirmation of Napolitano on account of her political background. The initiative, though ultimately short-lived and unsuccessful, brought the issue of student participation in university governance up for discussion.

The UC students’ reservations about Napolitano principally revolve around her time as Secretary of Homeland Security and her lack of experience in academia. Her role in deporting around 2 million illegal immigrants in that governmental position has given rise to fears about the status of undocumented students on UC’s campuses. Her background in cyber surveillance – a hot-button issue post-Snowden – has also aggravated a student body largely unsympathetic to the government’s position in the NSA debacle, and has particularly upset the student government. Students’ general discontent eventually pushed student leaders to consider a “no confidence” vote for Napolitano upon her taking up the position.

It is unclear how much effect a disapproving vote from the student body would have on Napolitano’s appointment. The issue centers on the concept of ‘student rights’ in general. As a practical possibility student enfranchisement lacks traction – student’s tenures at colleges are short, and presidents largely take on future-oriented responsibilities such as strategy and fundraising. But the philosophical question at the core lingers: should students have more of a say in the selection of their university president?

Consent is an important point in this debate. To many, choosing to enroll in a school can be seen as a rubber stamp for university policies. No one is forcing young adults to go to college, or forcing them to go to any specific college in particular. While these claims are true in the most technical sense, the tough job market and ever-increasing number of college-educated entrants into it mean the ‘choice’ not to go to college becomes a much harder one to take. The existence of competing colleges is a more convincing point – particularly with regards to private schools, like Brown. However, in the case of public colleges, financial pressures often compel students to take the state option. For the 2013/14 school year, UCLA will charge out-of-state students an additional $22,878 a year to attend: a considerable amount for students and families already straining to pay expensive tuition. But the high cost for students coming from outside California means incredibly lower tuitions for those coming from within the state – the cheapest payment plan for state citizens is half that for those coming from other parts of the country and the world. Public colleges in one’s home state present the most financially viable option for students can’t afford to be more selective with their schools. Students are virtually forced to take the state option if they want to go to college at all. As such, the argument that by choosing to attend the UC system, the students are implicitly endorsing the way in which the system is run, is a tenuous one.

Currently, students do have some say in the process of selecting new presidents. UC’s system allows for the establishment of advisory committees composed of students, staff, and alumni that are limited to 12 members each. While this is an encouraging sign and evidence that students’ considerations are taken into account, it’s more of a conciliatory gesture than a real dissemination of decision-making power. The key word is ‘advisory’ – the students are consulted, rather than given any concrete discretion over the choice of candidate. This hardly constitutes a substantial contribution, and pales in comparison to any semblance of voting or veto rights.

Closer to home, Brown’s presidential selection system suffers similar problems, though they have not resulted in any decisions as divisive as that of the UC board. Most recently used to appoint of Christina Paxson, the process included a student outreach program, in which open forums were hosted on campus to gauge the priorities of the students and allow them to express their opinions. As in the case of UC, this is a nominal and nonconcrete influence. More formally, there were only three students on the Campus Advisory Committee the last time a Presidential search was carried out, a paltry number considering the 8000 strong student body. Though meaningful student influence in Brown’s governance would be preferable to the current process, our school is a private institution with different expectations than a public college. The issue of student enfranchisement is much more pressing in an institution that is funded largely with citizens’ taxes.

A concern for both private and public school, however, is that the task of picking a new president is not a simple one. It requires expertise and a thorough vetting of many potential candidates. The assertion that thousands of students who have neither the time nor experience to properly carry out this scrutiny should not be trusted with decisions is a reasonable one. However, we trust voters of the same age as students to help elect the presidents, senators, congressmen, governors, and mayors of our nation. If anything, these are decisions with more weight and consequence appointing the president of a university. In governmental elections, the electorate is not simply offered a list of national candidates to pick from. Party primaries and by extension party members perform the task of sifting and sorting the candidates down to a few more explicit choices, which the general electorate can then choose between. In much the same way, the board of regents and corporate officers of a university could perform the detailed work that would be required to narrow the choices down to a manageable number. A situation in which students were involved in the process of the initial discovery and vetting of candidates would function like a watered down version of a campaign, which would be a disruptive influence on the running of a school. As such, the board could nominate a candidate, with the student body retaining the right of veto if the candidate aroused (as Janet Napolitano has done) a certain amount of ire with the student body.

The important thing to remember, is that after all the committees convened and all the ink has spilled, the student body will be the ones whose lives will be affected. They are the ones being educated, and it is their futures that will bear the impact. It is true that presidential selections are complex processes and, indeed, most students at the school at the time of a presidential selection would have finished by the time a new president’s influence began to be felt. Despite this, current and future students will likely hold many of the same considerations to be important, and the thousands of active alumni associations throughout the country show that many students continue to care about their alma mater even decades after graduation. Whether student enfranchisement in the UC system and beyond takes the form of councils, votes or vetoes, it is the college’s largest and most important constituency that should have the final say in who leads it.