There’s a pretty good chance I’m being tracked by the NSA. After some questionable Google searches for this article, some in-depth readings on anonymity browsers, and an accidental download of a view at your own risk PDF entitled “Basically everything you need to know about Tor,” I’m confident that I am now considered an “extremist” and my IP address is included in national security databases.

Recently, the NSA has been plagued by more than a few scandals regarding its dragnet collection of Americans’phone records and other online communications. While citizens argue that this infringement of privacy goes beyond the constitutional, the Agency argues that it is a necessary invasion to ensure the country’s security.

According to a 2013 ProPublica analysis, the NSA collects four main types of data: metadata of phone calls, Internet communications, Internet traffic and selected audio recordings of phone calls. Every day, service providers such as Verizon, AT&T and Sprint turn over billions of calls that have been stored for up to five years. Audio recordings of these calls can be provided if the call is to or from the United States or if one of the parties engaging in the call is suspected of being involved in international terrorism. Through the NSA’s PRISM program, major companies like Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, AOL, Skype, Youtube and Apple provide users’ emails, social networking messages and instant messages to the NSA upon request. Using a program known as XKeyscore, the NSA can monitor Internet traffic. This Digital Network Intelligence (as the NSA defines it) covers “nearly everything a typical user does on the internet,” including, web sites visited, addresses typed into Google Maps and files sent.

It would seem that with this incredible amount of data collection done in the name of national security, the NSA would be extremely effective at protecting American security. Unfortunately, that does not appear to be the case. An analysis of 225 terrorism cases inside the United States since the September 11 attacks concludes that the bulk collection of data by the NSA has “had no discernible impact on preventing acts of terrorism.” A White House-appointed review group supported this claim and found that the NSA counterterrorism program “was not essential to preventing attacks” and that much of the evidence it did turn up “could readily have been obtained in a timely manner using conventional [court] orders.”

In defense of such surveillance measures, the Obama administration and government officials have cited two specific cases where they claim NSA data helped make arrests. The first case is the 2010 conviction of would-be New York subway bomber Najibullah Zazi. According to chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, Mike Rogers, “I can tell you, in the Zazi case in New York, [NSA bulk data collection] is exactly the program that was used.” But according to British court documents, it was actually a UK investigation that led to Zasi’s arrest. The British used court-issued warrants to discover Zasi’s email contact with known terrorists in Pakistan and then relayed that information to the United States. The NSA’s surveillance cannot be credited with the Zasi’s discovery and subsequent arrest. The second case the Obama administration and government officials like to point to is David Headley’s. Headley was arrested under similar circumstances as Zasi and has been sentenced to 35 years in jail for scouting missions to support the Mumbai terror attacks. Although the Obama administration claims the discovery of Headley can be attributed to the NSA, an intelligence expert as well as a former CIA operative have both stated that the NSA’s data-mining sweeps were not key to the investigation and that such a claim was “nonsense. It played no role at all in the Headley case.” In fact it was again a British investigation that led to the tip-off.

An analysis of 225 terrorism cases inside the United States since the September 11 attacks concludes that the bulk collection of data by the NSA has “had no discernible impact on preventing acts of terrorism.” It turns out the NSA isn’t as successful at providing for the security of American citizens as it should be considering it collects data indiscriminately. However, there’s a reason for this lack of success — the NSA is looking for illicit Internet activity in the wrong places . As Bloomberg writer Leonid Bershidsky explains, “The NSA’s Prism surveillance program focuses on access to the servers of America’s largest Internet companies, which support such popular services as Skype, Gmail and iCloud. These are not the services that truly dangerous elements typically use.” Bershidsky continues to explain that “monitoring phone calls is hardly the way to catch terrorists. They’re generally not dumb enough to use Verizon.” Bershidsky is right, the NSA’s focus on the monitoring of the surface web presents very little in the way of identifying actual terror threats, as terrorists rarely make use of these services, most of which are commonly known to face government surveillance. It is for this reason, Bershidsky concludes that “the government’s efforts are much more dangerous to civil liberties than they are to al-Qaeda and other organizations like it.” Illegal activity tends to occur in another sphere of the Internet, one that most Internet users are unfamiliar with — the “deep web.”

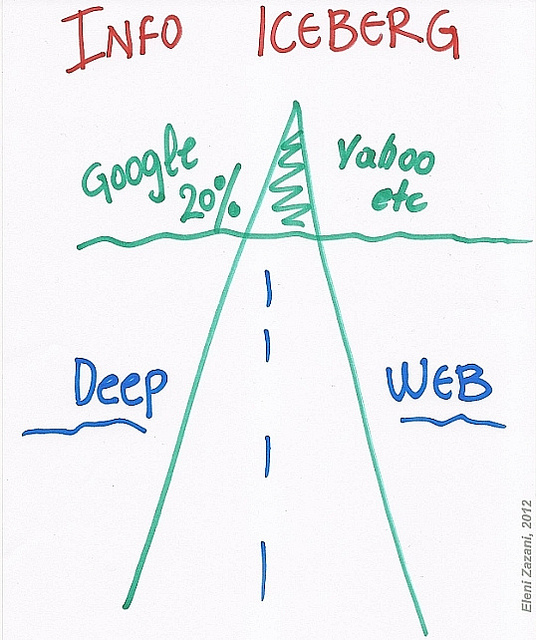

The deep web is not accessible through standard search engines and is massive in scope. The surface web, where a majority of NSA surveillance takes place, comprises less than 1 percent of the entire World Wide Web. To better understand the size discrepancy between the surface and the deep web, think of an iceberg: a glacier with a small cap above the water’s surface and a large body submerged in the water . The cap — what is visible above the surface — is the indexable Internet that the majority of us are familiar with. The vast majority of the glacier is submerged below the surface — this is the deep web. This incredibly vast under net isn’t always as malicious or mysterious as its name implies. A report in 2001 (unfortunately the most recent report to date) estimates that 54 percent of the deep web’s sites are databases or dynamic pages that can’t be captured by normal search engines (i.e., they’re content isn’t milled through by Google or Yahoo and won’t appear through a normal search). The largest of these databases belong to government agencies such as NASA, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the US Patent and Trademark Office. These websites are all public, legal and perfectly harmless. Another 13 percent of the deep web is made up of corporations’ or universities’ internal networks where the access points to message boards, personnel files or industrial control panels are located.

And then, there’s the dark net. This portion of the deep web is as mysterious and more malicious than its name implies. This collection of “secret websites” requires special software to access. Services such as illicit drug and weapon marketplaces, hired hit men, and pedophile rings populate the dark net and present a frightening culture of illegal internet activity.

This dark web is also a breeding ground for jihadist ideals. It supports an extensive infrastructure of extremist forums and gathering places where like-minded jihadists interact and plan actions. According to a report by the General Intelligence and Security Service of the Netherlands, “Virtual gathering places constructed, administered and secured by fanatical jihadists are hidden inside this invisible Web [the dark web].” A number of influential jihadist Internet forums act as the de facto core for terrorist organisations and propel the global virtual Jihad movement. The report estimates that approximately 25,000 jihadists originating from over 100 countries belong to this group of core Internet forums. On these core forums, news topics are discussed from a jihadist perspective, newly issued jihadist propaganda material is commented on, individual forum members make suggestions for possible targets and jihadist martyrs are glorified. These forums are also where virtual networks form and attacks are plotted and prepared for by extremist members. Frighteningly, global participation in such forums continues to increase. From 2001 to 2011, these forums saw a 99,900 percent user growth in Afghanistan, a 52,900 percent growth in Somalia, a 14,796.7 percent growth in Syria and 15,560 percent growth in Yemen (unfortunately, no evidence for the United States was listed in the study), as these countries experienced exponential growth in access to the Internet. This growth in core forum participation is not limited to the Middle East, as, according to the report, “These forums offer a unique possibility for Western jihadists to get in touch with likeminded individuals in jihadist conflict zones, such as Afghanistan and Yemen.”

This dark web is also a breeding ground for jihadist ideals. It supports an extensive infrastructure of extremist forums and gathering places where like-minded jihadists interact and plan actions. According to a report by the General Intelligence and Security Service of the Netherlands, “Virtual gathering places constructed, administered and secured by fanatical jihadists are hidden inside this invisible Web [the dark web].” A number of influential jihadist Internet forums act as the de facto core for terrorist organisations and propel the global virtual Jihad movement. The report estimates that approximately 25,000 jihadists originating from over 100 countries belong to this group of core Internet forums. On these core forums, news topics are discussed from a jihadist perspective, newly issued jihadist propaganda material is commented on, individual forum members make suggestions for possible targets and jihadist martyrs are glorified. These forums are also where virtual networks form and attacks are plotted and prepared for by extremist members. Frighteningly, global participation in such forums continues to increase. From 2001 to 2011, these forums saw a 99,900 percent user growth in Afghanistan, a 52,900 percent growth in Somalia, a 14,796.7 percent growth in Syria and 15,560 percent growth in Yemen (unfortunately, no evidence for the United States was listed in the study), as these countries experienced exponential growth in access to the Internet. This growth in core forum participation is not limited to the Middle East, as, according to the report, “These forums offer a unique possibility for Western jihadists to get in touch with likeminded individuals in jihadist conflict zones, such as Afghanistan and Yemen.”

After a suicide attack that killed seven CIA employees and one Jordanian citizen, Humam al-Balawi, the former moderator of the then al-Hesbah core forum, said in a statement on several core forums: “Beware, beware that you are satisfied with writing on the forums without going to the battlefield in the Cause of Allah… I see no path to this paradise except for death in the Cause of Allah.” In 2008, another member of these forums, Abu Omar, wrote, “From the moment I wake up until the moment I go to sleep, this is what I go throughout the day…. My thoughts are limited to the following questions: How can I terrorize the enemy.” Abu Omar managed to reach Iraq a year later, where he was killed in an air raid before he was able to carry out his planned suicide attack. More recently, groups like ISIS have used these forums to encourage attacks on American soil. One post in an ISIS message board includes a comprehensive guide to building pipe bombs using easily obtained materials like match heads, sugar and Christmas lights. Titled “To the Lone Wolves in America: How to Make a Bomb in Your Kitchen, to Create Scenes of Horror in Tourist Spots and Other Targets,” the post suggests attacking Times Square and Las Vegas, but also says tourist sites in Texas and metro stations throughout the United States would make good targets.

For an agency dealing in national security, the centralized, anonymous participation in illegal activity that occurs on the dark web is a major red flag. And although the NSA predominantly deals with surface web activity, it hasn’t been absent from the fight against this anonymous, deep web crime. The NSA has been targeting the Tor browser, the most popular software used to access the deep web, since 2006. And the NSA’s Application Vulnerabilities Branch is responsible for attacking the system. According to a report from the NSA, it has attempted several methods for attacking the network that, if successful, would allow it to uncloak anonymous traffic on a “wide scale.”

The Tor browser, an online anonymity software that allows for browsing of the deep web while resisting censorship, works through a process dubbed “onion routing,” referring to the use of layers of encryption (like the nested layers of an onion) to anonymize communication and activity. In encrypting the original data — like the user’s IP address — the Tor browser sends the information through a virtual circuit of randomly selected relays, with each relay decrypting only a layer of encryption at a time. Ultimately, the data reaches its destination without displaying the original source of the IP address and instead displays the last relay the data passed through. In this way, the Tor browser hides the users’ identity, allowing for secretive browsing of the deep web.

Use of the Tor browser is not limited to the dark net: Tor is utilized by many, including journalists, government agents and individuals, who have an interest in keeping their internet use anonymous or their identity masked. But the darker side to Tor, specifically its use as an avenue for accessing the dark net, remains an attractive tool for criminals and terrorists. And in many cases it’s the only path through which users can gain access to the dark web.

One successful technique developed by the NSA to target illicit users of Tor involved exploiting the Tor browser bundle for Mozilla Firefox, referred to by the Agency as a Computer Network Exploitation (CNE). To carry out these exploitations, the NSA actually makes use of its vast surface data collection programs like XKeyscore by creating “fingerprints” that detect htp requests from the Tor network to identify users. After identifying Tor users, the NSA uses a network of servers to redirect these users to a set of servers codenamed “Foxacid” where their browser bundle is then attacked. The program that the NSA used in exploiting these bundles was named EGOTISTICALGIRAFFE, before a recent Firefox update prevented such attacks. Despite this fact, NSA documents make clear that, “research into new exploits remains active.”

On these core forums, news topics are discussed from a jihadist perspective, newly issued jihadist propaganda material is commented on, individual forum members make suggestions for possible targets and jihadist martyrs are glorified. The NSA has been making headway in the fight against the dark net. What’s unclear is the success or extent of this headway. There have been several recent, large-scale busts of major, illegal activity centers within the deep web that may or may not have involved NSA assistance. Because the NSA’s missions necessitate a certain degree of secrecy to be successful, the government keeps the NSA’s involvement under wraps. For example, the recent shutting down of an extensive narcotics marketplace known as the “Silk Road,” was attributed chiefly to the FBI, with credit also granted to the Drug Enforcement Agency, the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Homeland Security. The NSA isn’t mentioned as a partner in the bust even though it seems to have played at least some role. In the criminal complaint released by the FBI, Special Agent Christopher Tarbell ambiguously claims “another agent involved in this investigation (“Agent-1″)…conducted an extensive search of the Internet in an attempt to determine how and when the Silk Road website was initially publicized among Internet users.” It’s not only possible, but also highly probable that the “agent” was actually an NSA analyst; according to a 2013 article from Forbes, “The agent was either really lucky…or really savvy at using XKeyscore.”

Another such case involved the destruction of a Tor network hosting service known as “Freedom Hosting” that contained a large portion of the web’s child pornography. The bust, also associated with the FBI, led to the arrest of a man later called the “largest child porn facilitator on the planet,” and was a resounding victory for law enforcement in the deep web. But the question remains: What part did the NSA play? The malicious code used to take down the site exploited a security vulnerability in the open-source version of Firefox that the Tor network is based on — a program essentially identical to EGOTISTICALGIRAFFE from the NSA. The administrator of the Tor Project posted on the project’s blog, stating, “The current news indicates that someone has exploited the software behind Freedom Hosting.” This exploitation was likely the product of the NSA’s attack on the Tor browser through the Firefox bundle.

The government’s secrecy surrounding the NSA is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, a certain amount of secrecy is necessary to protect the agency’s missions and chance of success. On the other hand, the secrecy makes it hard to judge the extent to which the NSA fulfills the mission it claims justifies breaches of Americans’ right to privacy: the protection of national security. If these busts really did involve the NSA, then the Agency has had a part in some incredibly important dark net busts. However, these isolated achievements in no way signify that the NSA has made significant advancements in the realm of identifying terrorist activity lurking within the deep web. Furthermore, it does little to justify the mass collection of Americans’ phone records, emails and Internet searches, since those who use terrorist forums rarely make use of the surface web. The users erase their social media accounts and consider the expression of their ideals on such “kuffa” (infidel) sites to be unacceptable and unsafe. One forum member stated, “Your talk on YouTube can be monitored by the Kuffar. Many a brother was arrested based on intelligence from YouTube; they will not hesitate to handover your IP details to Kuffar. Therefore, it is NOT the place you should be social networking.”

Monitoring the surface web in the hopes of occasionally identifying Tor users through their activities will not suffice to ensure the security of Americans against real threats existing within the deep web. Instead of immense bulk collections of data, other means focusing on the dark net need to be developed. As Bershidsky advises, “[the deep web] must be infiltrated by more traditional intelligence means, such as using agents posing as jihadists or by informants within terrorist organizations.” The NSA needs to be focusing on this sphere of the Internet by stepping up deep web surveillance, especially concerning terrorist activity, either in conjunction with surface web surveillance or largely in place of it. These changes would not only make the agency more effective at protecting the security of the nation, but would also prove to the public that the surveillance isn’t going to waste, allowing the NSA to justify its data collection and improve its public image. To the NSA agent reading this article: You’re welcome for all of the advice…now, please, stop tracking me.