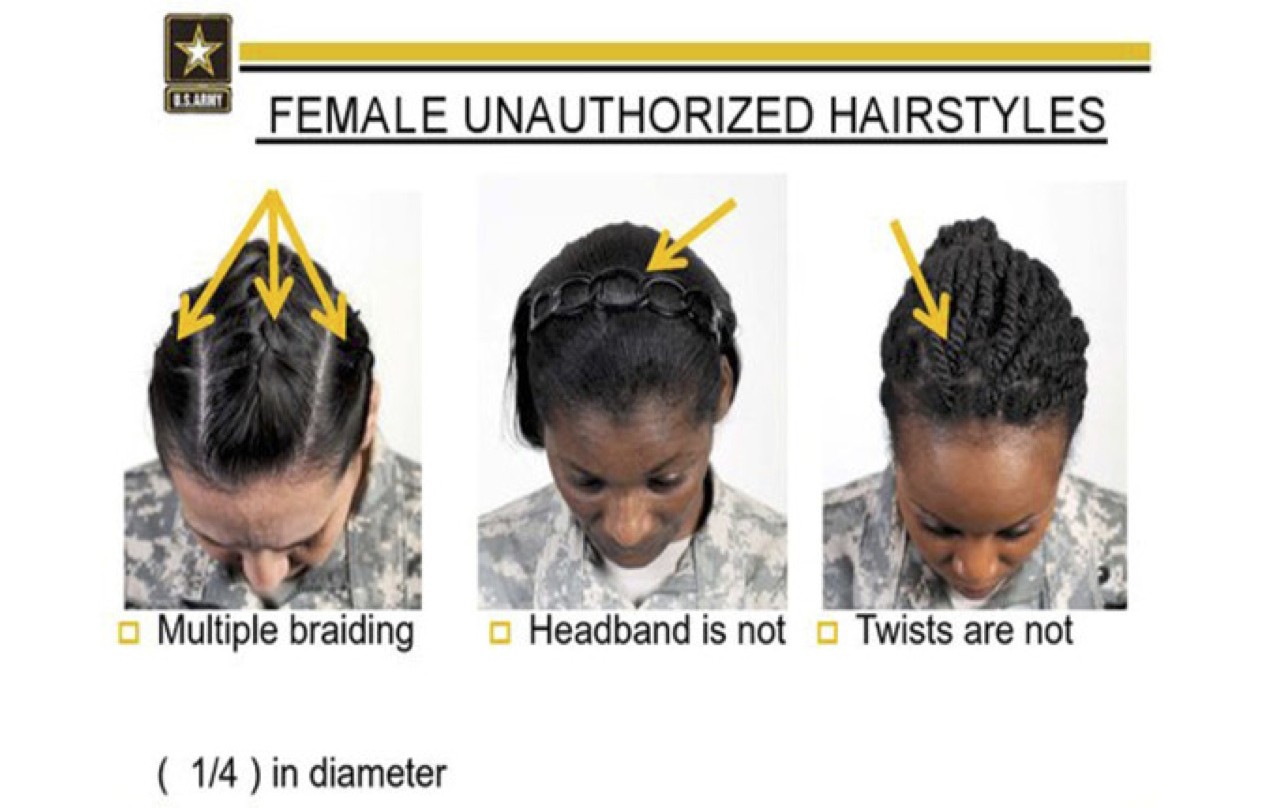

This April, the US military authorized new hair regulations that prohibited several natural black hairstyles, including dreadlocks, cornrows and hair that extends more than two inches from the scalp. Public outrage over the decision and allegations that the new policy was racist pressured the Army, Navy and Air Force to change their dress codes to be more inclusive of popular African American hairstyles in August. Regardless, the military’s initial implementation of this code reflects an attitude towards nonwhite physical characteristics — in this instance, specifically traditional black hairstyles — that is still very pervasive in American society. Although legislation has addressed some of the discrimination towards women with nonwhite characteristics in the work place, other instances demonstrate lines too elusive or complex to be effectively drawn and accounted for. Many company dress codes and personal anecdotes from women in the workplace illustrate that in modern American society, traditionally white characteristics are often equated with professionalism.

Many African American women are torn in the natural-versus-straightened hair debate, a decision that can often very well cost them their jobs. The dearth of women of color in positions of power in the United States often forces nonwhite women who want to enjoy successful careers to make a difficult choice.

In many workplaces, company policy makes that decision for them. Even though Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 makes it illegal for a professional dress code to discriminate based on race, many big companies such as Six Flags and FedEx have been challenged in the past few years for having policies that ban dreadlocks. Many argue that dreadlocks carry deep significance in African American culture. To ban dreadlocks in company dress codes is to correlate a part of black culture with unprofessionalism, and limit the ways that black employees can wear their without chemically processing it or wearing a wig.

After receiving much criticism for its policies, FedEx began monitoring managers to make sure employees with dreadlocks were being treated appropriately, but other companies have resisted changing policies, sometimes in spite of public criticism and even court cases. In the 1981 case Rogers v. American Airlines, the Southern District of New York court ruled that American Airlines was entitled to prohibit employees dealing directly with customers to wear their hair in braids against allegations from the plaintiff that the policies prohibited African American women from wearing their hair in a style that has deep cultural significance. The court ruled in this way under the logic that since the law does not target only black women, but anyone who might want to wear his or her hair this way, it does not discriminate based on race. This decision does not take into account the cultural significance that braided hairstyles have for many black women. It also set the precedent for courts to continue ruling in favor of companies that choose to adhere to such discriminatory codes, as exemplified in the more recent case of Pitts vs. Wild Adventures, Inc.

Not all appearance-based cultural discrimination is explicitly coded. While it is somewhat straightforward to notice codes that discriminate against certain racially rooted hairstyles, often the discrimination is not so tangible. When bias against individuals based on hairstyles exists in attitudes and not codes, they are harder to point out and confront.

Jamia Wilson, for example, is a successful feminist media activist who used to aspire to be a television journalist until she was pulled into the office of one of her professors during college and told that due to her effective skill as a speaker she could have a successful career in broadcast news, but only if she straightened her braided hair. Unless she chemically altered her hair from its natural state, she would not look “professional” enough to report televised news. This discouraged Wilson so much that she ended up changing majors and ultimately her career path.

In order to succeed in high-profile professional careers, some ethnic women are willing to change their appearance by more invasive means. From 2005 to 2013, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons estimates that the number of procedures performed on Caucasians increased by 35 percent, the number performed on Asian Americans, Hispanics and African Americans increased by 125 percent, 85 percent and 56 percent respectively. Analysts plaudit that the divergence is in part due to the prevalence ethnic plastic surgery, or surgery performed with the intention of making a client’s features resemble those of another race. The procedures give recipients features typically associated with whiteness, such as creased eyelids and slender noses with prominent bridges. Individual conceptions of beauty aside, the prevalence of ethnic surgery has demonstrated the options women have resorted to in order to supersede obstacles in the workplace due to racial conceptions of beauty.

In 2013, television personality Julie Chen revealed on her program The Talk that at the beginning of her career she had undergone blepharoplasty: a surgical procedure that creates the double eyelid crease that 50 percent of Asians, including Chen, are born without. She decided to get the surgery when, after her boss told her that her eyes made her look “disinterested” and “bored,” a sought-after agent told her that he would not represent her unless she received the surgery. Her argument that she did not get the procedure to look “less Chinese,” but rather got it because her eyes hindered her from appearing professional further leads to questions about what it means to look “professional” in the US workplace.

The drastic measures many women of color take in order to succeed in the workplace is reflective of how gender and ethnicity discrimination remain entrenched in the workplace. Many are aware of the commonly quoted statistic that women averagely make 78 cents for every man’s dollar, but those numbers are only true when comparing white women to white men. The average African American woman makes 64 percent of what the average white man makes, and the average Hispanic or Latina woman only makes 54 percent. Women have been making recent strides in terms of closing the gender gap in representation of professional success. For example, women held 16.9 percent of fortune 500 board seats in 2013 compared to the 9.6 percent they held in 1995. However, not all women have advanced at the same speed. In 2012, while white women held 14 percent of Fortune 500 board seats, Asian, African American and Latina women held only a combined 3.2 percent of them.

Company policies that ban hairstyles traditional to African American culture and the increasing number of blepharoplasties performed in the United States demonstrate that a perceived correlation between whiteness and professionalism still exists in American culture. When a person is told that her natural hair or natural eye shape makes her appear less professional, whether the message is conveyed through company policy or a boss’s comment, the meaning is clear. As long as characteristics traditionally associated with nonwhite races remain the yardstick to which professionalism is measured, women of color will remain at an unfair disadvantage in the American workplace.