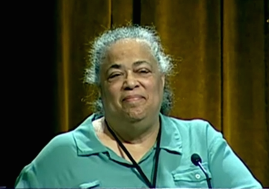

Dawn K. Smith is an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In May, the CDC began recommending that men who have sex with men (MSM), intravenous drug users and other high-risk groups take Truvada, a drug that can reduce the risk of contracting HIV by as much as 92 percent. Smith spearheaded the development of the CDC’s guidelines for the use of Truvada. Brown students and community members interested in this medication can contact the Division of Infectious Diseases at The Miriam Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island.

Brown Political Review: When did scientific literature first indicate that using Truvada before infection as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) might be effective, and when did the CDC first consider issuing this recommendation?

Dawn Smith: There were animal studies indicating that Truvada might reduce the risk of the monkey version of HIV called SIV in the mid- to late 2000s. At the end of 2010, the first large clinical trial testing Truvada in MSM published its results. Those were the first results that were definitive concerning how effective Truvada could be for MSM…The FDA [Food and Drug Administration] then looked at the results from that and other trials and made a recommendation that PrEP be added to the list of Truvada’s uses in the United States. At that point, we began finalizing a guidance document for the clinical practice of prescribing Truvada as PrEP. In 2011, we had issued interim guidelines for Truvada use by MSM and heterosexual adults. We did that because the drug was already available for treatment of HIV, and we knew that providers would prescribe it [as PrEP] in an off-label use. While we were working on the final guidelines, another trial presented its results in 2013, showing Truvada’s effectiveness with injection drug users in Thailand. Each time a new trial came out, it was necessary to update the draft guidelines. At the end of 2013, we went ahead with final approval and issued the 2014 guidelines.

BPR: What should public health charities and agencies in the United States be doing to inform sex workers, drug users and other hard-to-reach, vulnerable populations about access to Truvada?

DS: We think that a variety of stakeholders will be involved in informing key groups about the availability of PrEP, what it is used for, its effectiveness, what requirements there are for patients and how they can acquire it. These stakeholders can include state health departments, city and county health departments and community-based organizations that work with those populations. The effort can include the CDC insofar as it works with those organizations and public campaigns. I don’t think any one entity will drive the effort. We need all hands on deck.

BPR: In deciding to make this recommendation, how did you weigh Truvada’s public health benefits against the concern that it might encourage more individuals to practice unprotected sex?

DS: We issued clinical guidelines that are focused on safely delivering a drug to its intended population. We were not writing public health impact guidelines, rather guidelines for practitioners who have patients that may be right for PrEP. In the guidelines, we did emphasize that it is important to provide ongoing support for the use of other prevention tools while taking PrEP…We would like people taking PrEP to continue using condoms, if they are willing…Neither PrEP nor condoms are 100 percent effective, but when used together, you have even higher levels of protection from HIV.

BPR: The term “Truvada whores” was coined to stigmatize PrEP patients. What can be done to reduce stigmatization of the drug?

DS: The people who have used that term are a minority. It is my sense that reporting on the term’s use is more common than people actually using it. I think that as PrEP becomes mainstream, stigmatization will become less of an issue. There are people who disapprove of PrEP because they don’t think it’s a good idea, but that’s not the same as stigma.

BPR: Does any of the scientific literature indicate a risk that using Truvada as PrEP will lead to the development of drug-resistant strains of HIV?

DS: No. None of the trials showed any impact on drug resistance. The people who are taking PrEP are not infected with HIV, and without the virus present it can’t develop resistance. The only risk of resistance is for those few people who become infected with HIV while on PrEP. In the trials, what they saw was that people who accidentally started on PrEP while they were in the very earliest stages of HIV infection — the first week or two when the antibody tests were not yet positive — did develop [drug-resistant forms of HIV]. Amongst truly HIV-negative patients, however, who started PrEP and later became infected, there were only a couple of patients out of thousands who had very low levels of resistance to one of the components of PrEP…It seems likely from the models we are looking at that most of the drug resistance will develop in people who are being treated for their existing HIV infection, not in the few people who contract HIV while taking PrEP.

BPR: Are you optimistic that this new recommendation will lead to significantly reduced rates of HIV infection in the United States?

DS: If it is scaled up effectively, and if it is targeted at people who have a high risk of HIV, then yes, it will have an impact. Right now many of the people who need it the most don’t know about it…But [if used correctly], it will have a high level of impact on the epidemic…There are clear indications that if we do this right, we can drive down the incidence of HIV infection.