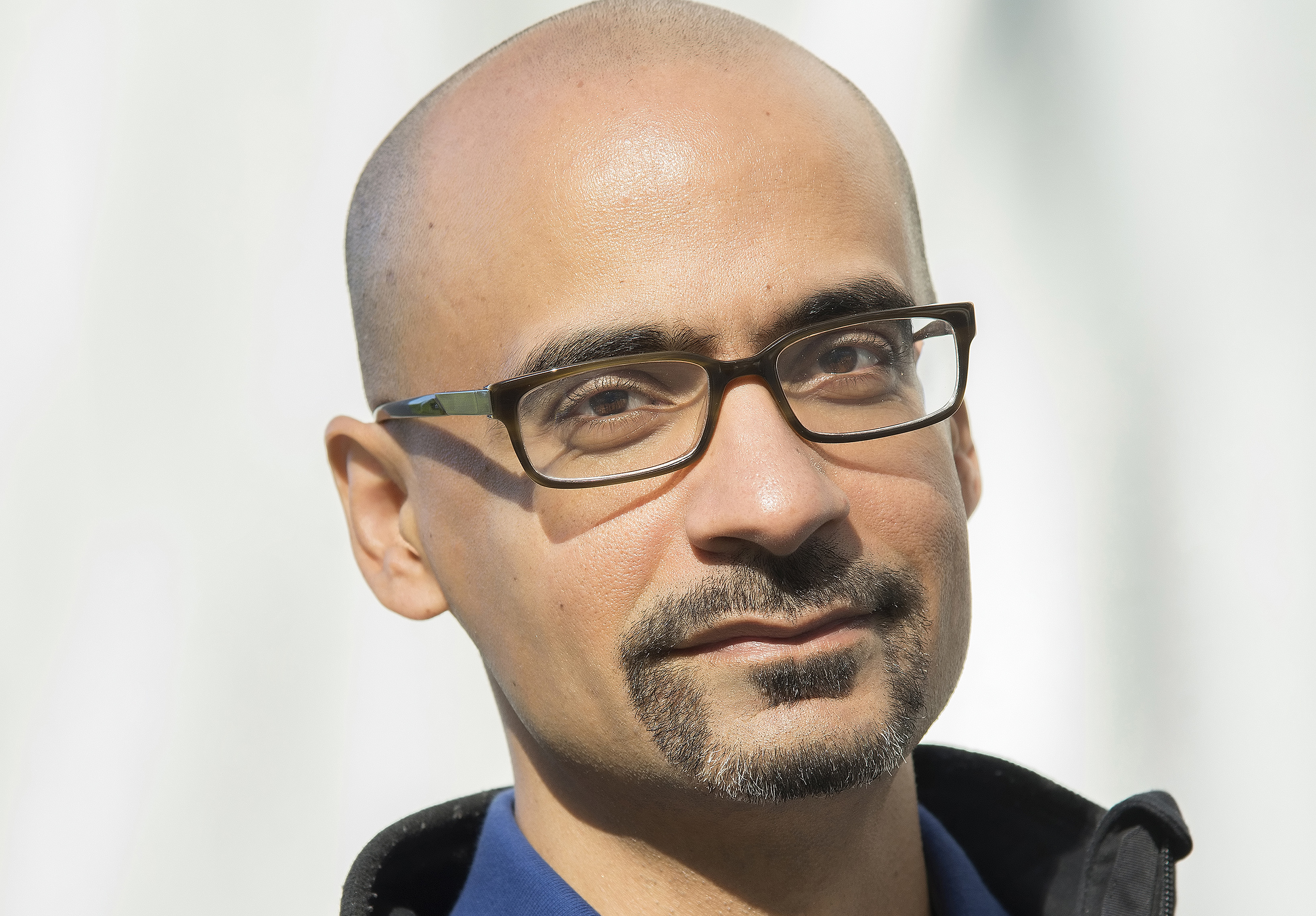

Junot Díaz, the 2008 winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for his novel “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” is a professor of writing at the Massachusetts Institutes of Technology. A fiction editor at Boston Review and a 2012 MacArthur “Genius” Fellow, Díaz was born in the Dominican Republic, and his most recent work of fiction, “This Is How You Lose Her,” was a National Book Award finalist and New York Times bestseller.

Brown Political Review: Obama recently announced that he will take executive action on immigration before the end of the year. Do you believe him, and how do you think he should approach this issue?

Junot Díaz: Well, he’s been promising for quite some time to enact or to move on immigration policy. It’s sort of like the coming of Jesus Christ: all foretold, never arrived, so we’ll have to wait and see. All I can say is that no matter what he does, his time as president is almost finished and he has been miserable when it comes to immigration policy.

BPR: Do you regard writing as an art form that is also an inherently political act? As a writer, and as a writer of fiction, how do you envision your role in relation to politics?

JD: Well, all art is politically charged. Everything that we consider the default or commonplace is framed by political ideology. So even people who claim that they are apolitical artists are deeply political. That’s just freshman art class 101. As far as the work is concerned, I understand my art to be a little distinct from my civic engagement. Sure, I do my art, and I hope that my art breaks all sorts of silences. And I hope that my art raises all sorts of critical questions. I hope that my art opens people’s minds to certain realities, but I, myself, am not convinced that’s ever enough. I think we have to do civic work ourselves; we have to be engaged ourselves. My art can’t help hand out fliers and certainly can’t help give out food in a soup kitchen. But those are things that I can do on my own time. So while I have great dreams and hopes that my art produces progressive effects, I also think that, in the end, I have to be in there doing the work myself. It’s not enough to just outsource it to the art.

BPR: Your stories deal a lot with relationships between men and women, and they often feature some pretty misogynistic characters. But at the same time, your next book — a science fiction work work of science fiction — will feature a 14-year old female protagonist with superpowers. Do you think your work reinforces popular cultural tropes about gender roles and gender relations?

JD: I guess the question would be “does representation of reality reinforce reality?” We can’t answer your question without first understanding what the baseline for that question is. In other words, what is a priori here? What is the understanding? Is the understanding here that representations of sexism reify the patriarchy? It really depends on whether it is one’s belief that representation equals affirmation. Any representation somehow approves and reinforces, endorses and works to reify the ideologies that are supposedly representative. But I’m not sure that’s exactly how representations work. I don’t think that’s the nature of representation. My question would always be: “What percentage of males that you’ve encountered are misogynists?”

BPR: A non-trivial percentage.

JD: Exactly, so why would the representation of male misogyny be so striking, since it’s basically the default? Again, I think that the question for me is: “What exactly is the work that these representations are doing? What is the ideological work that these representations are doing?” And it’s not up to me to say, or to make that decision. That is the work of the reader. Again, I think that we’re already starting from perhaps a profoundly confused place, if the problems are the representations themselves. What is interesting for me is that I’m rarely asked about the sexual violence and the rape that I represent. I wouldn’t say rarely — I am never, never asked. No one ever says: “Junot, Mr. Díaz, Professor Díaz, you represent a lot of sexual violence and rape against women. Don’t you think you’re enforcing rape and sexual violence against women?” And the reason they don’t ask such absurd questions is because it’s pretty patent in the text that that’s not what’s happening. I think that encountering unvarnished traditional masculinity, encountering those kinds of discursive masculinities — like the ways that boys talk when there are no women in the room — is shocking for many folks. That is very striking to a lot of people and often very off-putting. Most folks like their misogyny well lacquered, well contained. They will endure the endless misogyny of Game of Thrones, but not read a book where a character’s interiority reflects their masculine assumptions and culturally accepted patriarchal assumptions. Folks will have Marie Claire, Vogue and Elle lying around. They don’t mind that commodification and objectification of women, but they’ll be troubled by a dumb-ass boy talking about a woman’s ass. I get asked this question a lot, and I like to point out that someone like Yunior, the character [featured in both “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” and “This is How You Lose Her”], certainly has a lot in common with an issue of Vogue or Marie Claire, which is to say that what’s the matter with Yunior is not about my representations but the larger framing ideology called patriarchy.

BPR: As a professor of writing at a top American university, what are your views on affirmative action?

JD: Recently there have been polls released where you see a large percentage of whites claiming that anti-white discrimination is as present and as toxic as discrimination against blacks. When you’re dealing with such counter-factual delusions, it is hard to have a conversation about something like affirmative action. When all sociological studies and all models show pervasive and deep inequalities across race, when scholarship again, and again and again underscores how racism deforms and limits the opportunities of people of color in this country. There’s this constant drumbeat of information that racism is not only pervasive, that racism is not only alive and well, that racism not only is embedded in many of our institutions — but also that it is a daily force in all of our lives. When you have all that stuff spread before you, it’s hard to say that we belong to a society that is completely just and requires no strategies to deal with these kinds of inequalities and profound structural racism. If folks really believe that we’re post-racial, that there’s nothing happening, you can imagine that something like affirmative action would seem like this unnecessary give away, like a free handout. But I think that if you understand and live in what I would consider the real world, you see how fucked up and omnipresent and disastrous racism is and how it impacts people’s lives. And then I think you might be more favorably disposed to some kind of legislative remedy. I, myself, predicate my support for affirmative action on a critical understanding of the role that white supremacy and white supremacist racism play in our national outcomes.

BPR: If you were a college student now, what do you think your biggest political concern would be going forward?

JD: There’s stuff that changes. We’re not static; there are things that are dynamic. For one, certainly the environment and climate change. While these issues were present when I was in college, they were not anywhere nearly as salient when I was in college. Unfortunately, there are some perennials, some evils that persist: patriarchy, white supremacy and the ravages of capitalism. These things have not diminished. In many areas, they have increased their dominion. As a young person, as a student, I was a more intersectional person than a single-issue person. If I could presume to imagine what my alternative self would be doing in college now, he would be engaged in issues surrounding increasing people’s access to and the presence of justice. If anything, the aspiration of justice has driven a lot of my civic interests. It’s also tough to be a student now. I’m seeing it from one end at the faculty level. This is a moment in our university system where privatization and the market logic dominate everything. Students [are] treated more as consumers every day and less like students. They’re being forced to live in a climate of competitive fear, versus a climate of wonder and inquiry and openness — those are the cornerstones of education and of a learner’s stance. In my dream world with my dream self, I would be engaged around the issue of how one learns, becomes a student and transforms oneself inside of a university institution that has become hyper-saturated by the logic of cash. How can we roll this back a little bit?

The “remedial” justification for affirmative action offered here — based on societal discrimination — is a nonstarter legally, since it has long been rejected by the Supreme Court. And rightly so: Why should race be used as a proxy for social disadvantage, when there are many whites and Asians who are poor (and are discriminated against in university admissions) and many blacks and Latinos who are well-off (including the overwhelming majority of those given admissions preference by universities)?