This week, Slovaks voted on a referendum that would have banned same-sex marriage in the country as well as adoption by same-sex couples. A sizable majority approved of the legislation, but it failed because more than half of the population did not turn out, nullifying the proposed bill. Given that just this June the Slovak government amended the constitution to define marriage as between a man and a woman, the referendum probably did not elicit much enthusiasm from the voting populace. However, it did receive substantial enthusiasm and support from Pope Francis, who holds significant sway in the overwhelmingly Catholic country.

Pope Francis’s campaign for the referendum may seem anomalous amidst the backdrop of his non-judgmental, liberal reputation. However, despite a significantly softer tone than his predecessors, Francis has begun to use his popularity to promote his, and by extension the Catholic Church’s, more illiberal views. Francis may be relatively more liberal than his predecessors, but the conservative Curia—the Church’s ruling body that has to sign off on changes to Church teaching and was shaped by the previous Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI—and relatively non-negotiable canon law may be stagnating any progressive doctrinal changes he supports. Nevertheless, Francis enjoys widespread popularity among Catholics and non-Catholics, especially in Europe and the United States, two of the Catholic Church’s least conservative constituencies.

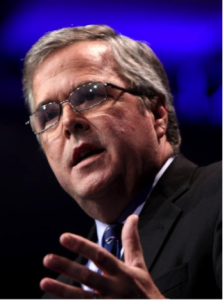

Domestically, Jeb Bush, though far less popular than the Holy Father, is revered by moderate factions and portrayed by the media in a similarly progressive light. He’s constantly referred to as the better Bush, the more enlightened brother and the voice of reason among a gaggle of ultra-conservatives vying to be the least liberal presidential candidate in the hopes of winning primaries. He’s the candidate of the establishment and of the moderates, a compassionate conservative.

So how does a Pope with little real progressive reform credit to his name earn the favor of Catholics yearning for the Church to veer in a more modern direction? Analyzing the “potential” candidacy of Jeb Bush as an unconventional parallel, the intentions of the Vatican’s successful public relations campaign propagating Francis become clear, and his resulting popularity understandable.

Early in his papacy, Francis made headlines throughout the world by claiming that the church needed to be more open and less judgmental, specifically of women and the LGBTQ community. The novelty of the new “Vicar of Christ” who had seemingly decided to reject the orthodoxy and conservatism of the papacies before him excited even the most ardent liberals, from Rachel Maddow to Bill Maher, who routinely praise his more progressive stances and remarks. Jeb Bush, similarly, is touted as the thoughtful alternative to more inflammatory, extreme GOP candidates, such as the likes of Ted Cruz.

Both men have used tone softening as a strategy to win over moderates and bolster their moderate credentials, separating themselves from their more extreme colleagues. Same-sex marriage is a particularly poignant example of how both men have used less inflammatory rhetoric to build a kindly persona of themselves. Francis shocked the world and pleased liberals by decrying judgment of gays, while Bush claimed recently that the flurry of judicial rulings legalizing same-sex marriages in the United States ought to be respected. They both struck a distinctly less controversial tone than their respective counterparts. Pope Benedict XVI called gay marriage an “attack” on traditional families and a “manipulation of nature.” Similarly, potential GOP Presidential candidate Mike Huckabee recently compared homosexuality to drinking and cursing.

Unfortunately, little substance has come from their increasingly compassionate rhetoric. Francis convened a council to discuss matters of the family last year, which would have been the time to announce any legitimate, even minor, changes in Catholic teaching on divorce, homosexuality, or the like. No such changes have occurred. In Slovakia, the Pope’s softer rhetoric evidently means little to sexual minorities in a country where the Vatican exerts significant influence. Jeb Bush, similarly, may claim that his respect for court rulings makes him a moderate, but his position is essentially as conservative as Marco Rubio’s, Scott Walker’s, and Ted Cruz’s. Of course, none of them support same-sex marriage, but none of them have authority over court rulings. They may act more infuriated than Jeb Bush does publicly, but they will obviously respect the rulings as well. Semantically, Bush strikes a less radical tone, but in terms of action, GOP contenders—whether it be Cruz or Bush—can do nothing.

Furthermore, their soft liberal rhetoric is incongruent with their blatantly conservative actions in recent years. As governor of Florida, Bush was radically pro-life, even forcing the reinsertion of a feeding tube keeping Terri Schiavo, who was in a “persistent vegetative state” from dying despite her husband’s wishes. He referred to LGBTQ and feminist movements as “modern victim movements,” and opposed designating anti-gay violence as hate crime. He sped up the process of executions in Florida, allowing for fewer appeals, and advocated for harsher sentences for drug abuse. He even opposed government-mandated safety belt legislation. Clearly, Bush, as governor, was neither liberal nor moderate. Nevertheless, he is touted as the candidate of the “moderate” Republican establishment. In fact, some claim he may be too liberal to even win the nomination.

Similarly, and contrary to popular belief, Francis’s recent actions have followed an illiberal trajectory. When asked about the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, Francis’s response was, “You cannot insult the faith of others,” abandoning a more balanced and nuanced position. Instead of criticizing the magazine’s offensive racial content while upholding free speech rights, he argued for a preservation of all forms of religious orthodoxy. Earlier in the week, he blasted those who abstain from having children as “selfish” people who contribute to a “depressed” society, sharply qualifying previous statements he made claiming it is not a Catholic’s duty to constantly reproduce. His staunch conservatism of the past weeks culminated in his calling the anti-gay Slovakian referendum, which would have banned same-sex couples from forming families with parentless children, ironically, a “defense of the family.”

The implicit conservatism of the two public figures begs the question: how do Pope Francis and Jeb Bush still elicit praise from the left, and how did they become the faces of their respective moderate factions? Part of the answer is that along with a tonal contrast to their predecessors and counterparts, they’ve both championed certain pet liberal issues. For Bush, he is a supporter of Common Core, a set of national education standards and guidelines, which were once praised by the Republican party. However, even its foremost advocates, namely Governor Bobby Jindal, are distancing themselves from the Core as they hope to win primaries with a Republican base that largely opposes it. On immigration, too, Bush is far more progressive than his potential primary opponents, supporting comprehensive immigration reform that includes a path to citizenship and amnesty.

Pope Francis’s pet liberal causes also make a convincing case to his moderate support base. While tackling sex abuse is not overtly liberal, it oddly is not a priority of the Curia’s most conservative members. On that front, he has certainly taken a determined stance to fix what he calls the “leprosy” that is sex abuse perpetrated by Catholic leaders. He’s also championed a more resolute liberal position on climate change. Prior to the UN Paris Summit this year, he will release an encyclical calling on those attending to act swiftly. This sharply contrasts the last encyclical of his predecessor, Benedict XVI, which was more of an elementary Catholic Sunday school lecture than a call to action from the one whom Catholics believe is in closest contact to God. Francis’s integral role in reestablishing diplomatic ties between the United States and Cuba infuriated conservatives so much so that even Cuban Republican Catholic Marco Rubio criticized him.

Pope Francis and Jeb Bush have similar problems. They both must deal with extremely conservative elements of their respective parties while looking to the future. As the youth become less religious and less conservative, these two men will be tasked with cementing the relevance of their respective institutions as their most conservative elements die off. Bush seems to be playing both sides ideologically, and while he champions a few liberal causes, he still panders more to the most extreme in his party than he does to the moderates. His views remain incongruent with younger generations, especially on social issues, which degrades the “thoughtfulness” of his credentials. Francis, on the other hand, seems keen on leading Catholicism into a new era, perhaps even a more thoughtful, open-minded and liberal one. But as of yet, nothing has changed. If Francis’s recent statements in support of antiquated ideas of civil marriage and the necessity of procreation mean anything and the rigid, stubborn nature of canon law and its interpreters persists, nothing will come of the these moderate public figures’ rhetoric. The future of the GOP and the Vatican, regardless of the thoughtfulness and pragmatism of their respective leaders, still seems like an incredibly conservative, outdated and exclusionary one.