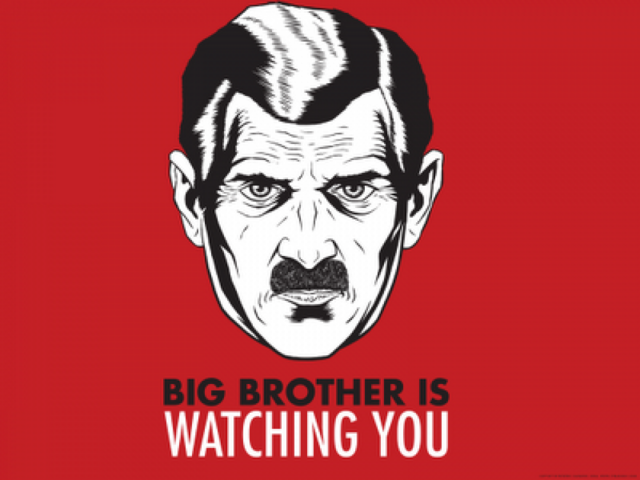

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen….” So begins George Orwell’s dystopian classic, 1984, originally published in 1949. In 2017, nearly 70 years after being written, the novel has resurged to the top of several bestseller lists. Set in Oceania, a totalitarian police superstate controlled and heavily surveilled by the Inner Party and its odious leader known as ‘Big Brother,’ 1984 is a stark condemnation and cautionary tale of blind hyper-nationalism and governmental overreach. Readers across the United States seem to be turning to Orwell’s literary masterpiece in an attempt to find some explanation, some prophetic elucidation, of the current state of the nation and our world. As one reads the day’s news, plastered with alarming headlines of antithetical governmental action and the constant repetition of that name, there is certainly an aura of peculiarity — a total aberrancy and almost a perversion of reality; the thirteenth bell of the clock might not surprise any of us. This is why 1984 has succeeded in attracting readers almost seven decades after its publication; although on paper it appears far-fetched and somewhat apocalyptic, Orwell masterfully pinpoints human behavioral and ideological strains which evoke the possibility of a future in the United States not too distant from that of Oceania. Yet, as entrancing and captivating as the dystopian narrative of 1984 is, Orwell offers us arguably even greater meaning through his own life and in some of his other literary work.

Eric Arthur Blair, best known by his pen name “George Orwell,” was born in Motihari, British India, in 1903. When he was quite young, he joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma; his experiences there inspired him to write his first novel, Burmese Days, in which he explores the dark nature of imperial and colonial society. This work marked the beginning of Orwell’s deep exposition and denunciation of oppressive governmental apparatus. In 1936, however, Orwell decided to take direct action. Deeply concerned with Francisco Franco’s uprising in Spain and the rise of fascism throughout Europe, he flew to Barcelona to join the Republican cause. In Spain, Orwell encountered a highly fractured and complex political situation; the legitimately elected Republican government was backed by an army composed of numerous factions with opposing strategic and theoretical views, the main ones being the anarchist-leaning POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification) and the PSUC (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia), the official wing of the Communist Party in Spain, which was backed by Soviet arms.

Having spent several weeks on the military front — although witnessing little action — Orwell was injured by a bullet to the throat, which narrowly missed his arterial vein, and was prompted to return to Barcelona. Tensions between the opposing factions had been high in the city and fighting eventually broke out in an episode that became known as the Barcelona May Days. This is when Orwell came into firsthand contact with the Communist propaganda machine, an encounter which would have profound, lasting effects on the writer. The Communist press had undertaken a campaign of lies and distortion against the POUM, the party which Orwell had fought for. They labeled the anarchist-leaning party as Trotskyists and accused them of collaborating with the fascists; seeing the propagation of falsehoods against those fighting for the same, supposedly revolutionary cause profoundly disturbed Orwell. As the situation deteriorated, the Communists tightening their grip on the Republican cause and banning the POUM, Orwell escaped Spain by train, eventually returning to England.

His entire experience during the War is recounted in one of his best and most underrated works, Homage to Catalonia. The book received little attention and was largely neglected upon publication, being released in the United States only in 1952. At a time when the Stalinist — and Communist — status quo monopolized much of the revolutionary narrative across the globe, criticisms of the mainstream machine were automatically deemed counterrevolutionary. Nevertheless, Orwell unflinchingly proceeded to push his criticisms toward the machine. Herein lies one of his greatest qualities as a writer and literary figure: Orwell always writes his conscience. His prose flows out of his internal vision of the world and moral compass, regardless of partisanship or ideology, as especially evinced in Homage to Catalonia. He never writes for us, or attempts to impose on us a specific moral outlook on the world; rather, he simply writes what he sees, and how sees it, with brutal honesty. We are left to think for ourselves, to make our own conclusions about the world: all Orwell does is point the direction. Through this, Orwell provides us a powerful antidote for our own times. The increasing proliferation of polarizing partisanship consists heavily of imposing and adhering to certain pre-conceived moral narratives. In Orwell, however, it is essential for the individual to see the truth for himself and derive his own conclusions — a practice deeply lacking in our current political sphere, and one which might go a long way in combating the toxic dichotomous polarization that plagues us. Orwell’s experience in Spain would also inspire him to write another of his most celebrated novels, Animal Farm, which retains and emphasizes all his aforementioned qualities.

Animal Farm, released in 1945, is an allegorical story of the Stalinist era, and a hard-hitting criticism of its machinations. In the novella, Orwell depicts the popular, romantic uprising of oppressed farmhouse animals against their human owners, and then the complete distortion of the cause by its leaders, the pigs, once they attain power. Here, Orwell exposes his greatest qualities as a writer. He cuts deep into the Stalinist system and the false promises made at the expense of the hopeless through brilliant satire. He does not need to tell us how and why Stalinism is wrong, he does not need to pontificate; all Orwell does is lay bare and clear that which to him seemed obviously absurd, but that which to many was not. This is a sign of true genius; being able to see as obvious that which eludes so many others. Animal Farm, along with 1984, remains as one of the most relevant pieces of literature of our times. It reminds us of the power of rhetoric, and the enormous distance that can exist between it and the truth. It teaches us to be wary of those who promise, but provide little substance, and thus prey upon the hopes of the hopeless. Above all, Orwell teaches us to never take our eyes off those in power, even if we ourselves have given it to them; a pertinent lesson for our times, if there ever was one.

If 1984 is to be revived and brought into the popular cultural sphere once more, Orwell — his logic, being, and implications — should come with it. He, more than any other, reminds us of the power of literature and its capability to reflect and explore humanity’s relations to power. We should read Orwell’s masterpiece not because it fuels our cynicism of the current state of things, as grim as they may be, but because it provides us with the powerful tools to resist and overcome it. In times of vitriolic nationalism, undying allegiances to ideology and narratives, and the blurring of the line between truth and falsehood, Orwell is nothing short of essential. Although political action is of course pragmatically important, especially in these times, it is enduring works such as that of Orwell’s that help formulate a resistance much more profound in nature: a true, deep-seated, emancipation of the mind. It is this art that reminds us of the invisible foundation upon which power rests, the one rooted in our own individual minds; it reminds us that we are essentially in control, but that we surrender it much too quickly. Yet, our times, possibly some of the most tumultuous and volatile of human history, are almost completely drained of this type of art. We should continue to read Orwell, to propel his work, in order to inspire individuals to realize the capabilities that exist within themselves and thus do away with chains before they can ever manifest themselves and cut oppression from its deepest roots.