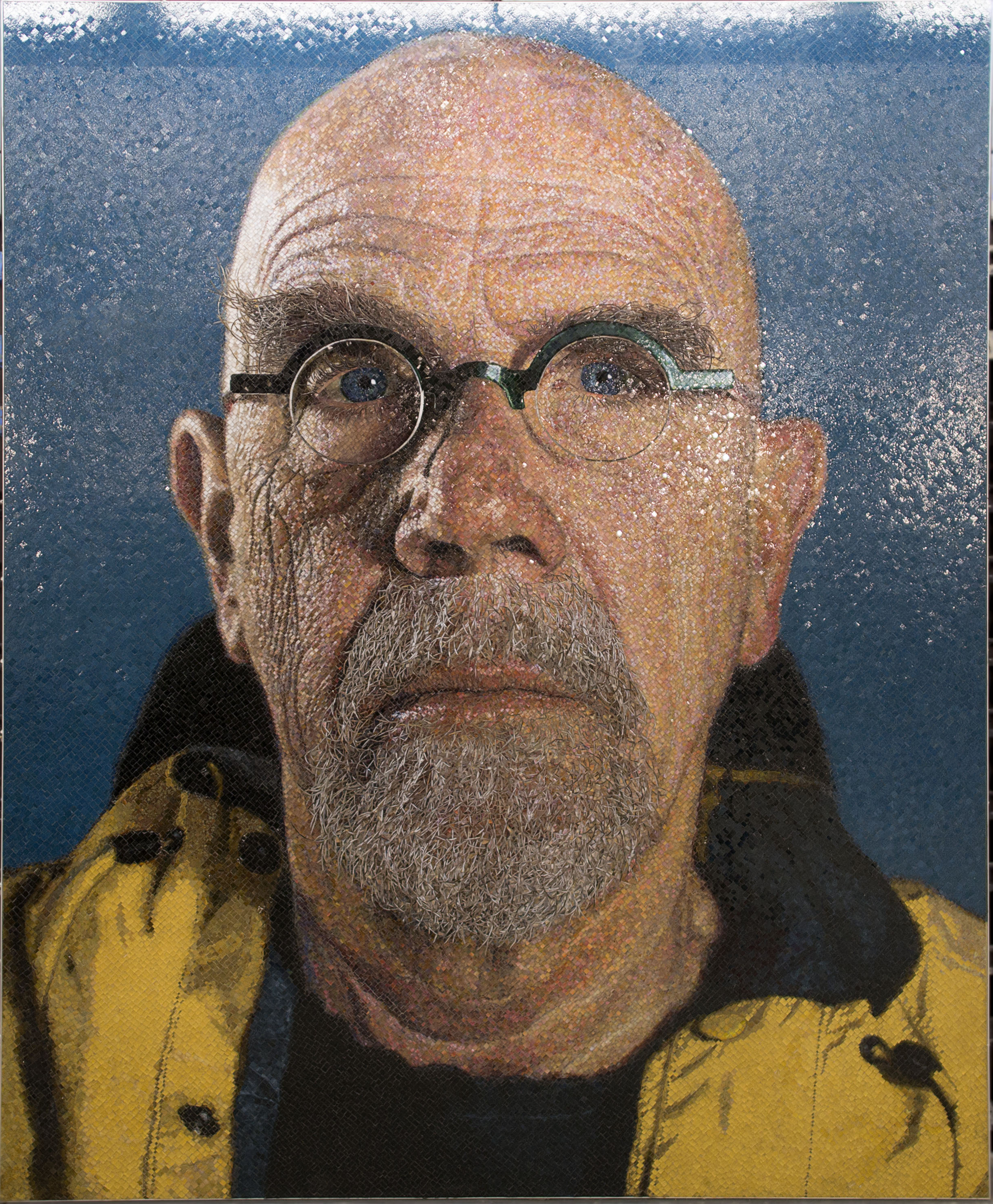

Amidst a flurry of sexual misconduct accusations against famous portrait artist Chuck Close, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. has decided to indefinitely postpone a Chuck Close exhibition that was in the books, while Seattle University has removed a Close self-portrait from its permanent collection. Both institutions have come under fire for their decisions regarding Close’s artworks, but museums should have the autonomy and freedom to discontinue their exhibitions if their decision is to stop funding a sexual harasser. Moreover, Close’s acts of sexual harassment are inextricably linked to his art itself; portrait art relies upon the individual relationship between model and artist, a relationship that Close allegedly abused for his personal benefit.

In the past few months, various high-profile cultural figures have been accused of sexual misconduct and artists have been no exception. Chuck Close, who has photographed a long list of famous subjects including Bill Clinton, Brad Pitt, and Kate Moss, is among the latest artists to come under scrutiny regarding sexual assault. Julia Fox, an artist invited to Close’s studio, claimed that Close insisted she take her clothes off before telling her that her “pussy looks delicious.” Langdon Graves, another artist invited to Close’s studio, stated that Close asked her to take her clothes off before recounting “sexual acts that he and a local waitress perform on each other.” Close, also known for his ‘Nudes 1967 – 2014’ series, a set of photographs and paintings of the human body compiled over five decades, did not deny any of the allegations. In fact, he stated that “last time I looked, discomfort was not a major offense. I never reduced anyone to tears, no one ever ran out of the place. If I embarrassed anyone or made them feel uncomfortable, I am truly sorry, I didn’t mean to. I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but we’re all adults.”

It would be a mistake to view Close’s actions as isolated incidents rather than as pieces of a larger, more reprehensible power structure that allows artists like Close to abuse and harass their employees. Bruce Weber and Mario Testino, two of the world’s most famous fashion photographers, have also been accused of sexually harassing several male models. In response, magazine publisher Condé Nast stated that they would no longer commission work from Weber or Testino and that any nudity or sexually suggestive poses must be agreed upon beforehand with the model. When an artist asks a model to take off their clothes or make sexually suggestive poses, it is not an innocent request or question, it is an attempt to pressure and persuade. Refusing to comply with the artist’s request would likely put an end to the relationship between the model and artist. We must be able to differentiate between sexual harassment and normal business operations, despite the fact that seduction and nudity are such integral elements of modern art. Portrait art, photography, and modeling are all fully-fledged professions. As such, the nature of their work should be treated like that of any other business: Contractually agreed upon nudity is acceptable, but it is inappropriate to ask for, or expect, nudity if it is not included in the business agreement.

Historically, acts of sexual harassment perpetrated by famous artists have been non-factors in the treatment of their work. In other words, artwork and an artist’s sexual misconduct have been treated as separate entities. Pablo Picasso, for example, notoriously committed acts of sexual abuse and harassment on several occasions; he threatened to throw one woman off of a bridge for seeming “ungrateful,” he branded a woman with a cigarette on her cheek for threatening to leave him, and he beat another woman into unconsciousness. Picasso’s work, though, has rarely been questioned, and not just because he is one of the most influential artists of all time: Picasso’s paintings do not depict the models he was accused of harassing; the images portrayed in his work are easily separable from his personal history as a sexual abuser. Another argument for the anonymity of his actions is that Picasso, who passed away several decades ago, cannot use the revenue that his artwork generates to fund an ongoing operation of sexual harassment.

Chuck Close’s work, on the other hand, is inextricably linked to the accusations of sexual misconduct against him in the public arena. As a portrait artist, Close’s canon of work has stemmed from his individual interactions with models. There is no point in speculating about the role that Close’s behavior towards models has had in shaping his previous works: Close’s work, which led him to win the National Medal of Arts in 2000 before being appointed to the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities in 2010, is so influential and engrained within art history that any attempt to editorialize his previous work would likely miss the mark. In Close’s 50 year career as a portrait artist, the first public accusation of sexual misconduct against him occurred in 2017. As a result, it would be purely speculative to assume that sexual misconduct has sullied his entire body of work.

Picasso’s artwork and his sexually abusive history can be separated because his misconduct never infringed upon his art itself. In the same vein, we have no evidence that Close’s works were influenced by sexual harassment until 2017 and, as a result, his older works should be separated from his current and future portraits that could be compromised by allegations of recent sexual misconduct. Now, when a museum chooses to display new exhibitions of Close’s work, they are aware that they are funding an artist who will continue to use sexual harassment as a professional tool. Every dollar that Close receives for his work is another dollar that will be used to fund sexually abusive practices and another dollar that will validate decisions to sexually harass models for the sake of creating art.

Museums should have the freedom and autonomy to choose what work they display. Some have said that the choice to indefinitely postpone the National Gallery of Art’s Close exhibition is a case of the #MeToo movement gone too far. Some say that Close’s work must be featured to create a dialogue about sexual harassment in the art industry. Some say that the closure of Close exhibitions could be a slippery slope that leads to mass censorship of artwork. First, a museum’s exhibition selections are not a form of censorship. Freedom from censorship means that people are able to express their ideas and opinions; it does not mean, however, that every idea has to be respected and featured for all the world to see. Second, we must not underestimate the power of the current national dialogue surrounding sexual harassment, but the discussion must be coupled with concrete repercussions. Third, and finally, museums retain the right, through freedom of expression, to fund the projects that will positively add to the narrative they are creating. Chuck Close’s older works, which are not linked with accusations of sexual misconduct, should not be removed from the annals of history. Close’s newer works, though, which are clouded with allegations of sexual harassment, should not be displayed in order to set the precedent that sexual harassment will no longer be tolerated within the artistic process.

Choosing to withhold funding and reduce the exposure of someone who uses sexual misconduct as an integral piece of his artistic process should not be controversial. Simply accepting Close’s work as a tool to continue dialogue about sexual harassment is not enough. Choosing to label each of Close’s paintings with an asterisk signifying his history of sexual harassment is not enough. The only way to prevent sexual harassment from artists like Close, Weber, and Testino is by refusing to create a market for their work. Without a place for them to show their art, art that is a byproduct of sexual misconduct, they will be forced to adapt or simply shut up shop. Anything less than a rejection of Close’s new artwork would be a fairly transparent approval of sexual harassment in the art industry.

Chuck Close is in a wheelchair. A wheelchair! How can any woman feel he has power over them? The women were hired to be nude models. Hired to remove their clothes. And they are offended by a remark? Get the fainting couch. Women need to stop acting like helpless Cassandras and take responsibility for their choices.