The 2020 Presidential campaigns have thus far been characterized by lofty, idealistic promises for change. These types of simplistic and grandiose proposals tend to galvanize voters and garner support. They do not, however, serve to inform the American public about the candidates — one of whom is to become the next leader of the free world. As candidates compete for limited airtime and we approach election crunch-time, we should expect that these idealistic, often unsubstantiated plans will only increase in quantity — and in eccentricity. The costs of these plans will likely go undiscussed.

To temper national skepticism regarding the viability of bolder proposals, some candidates appear to be obfuscating the true costs and requirements of their plans. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), for example, has already proven to be less than forthcoming about the costs of his Medicaid-for-all proposal, which has received widespread democratic support, even though the feasibility of instituting such a healthcare plan is tenuous. Both North Carolina and Vermont considered implementing medicaid-for-all, ultimately nixing the plan because of its prohibitively high cost.

The dissemination of accurate information regarding the cost, feasibility, and consequences of various political proposals is necessary for American citizens to cast well-informed ballots. This rings especially true right now: In the 2020 presidential primaries, voters must select one out of twenty four Democratic candidates. If voters are not provided with consistently honest and clear information about candidates’ platforms, it will be nearly impossible for the Democratic Party to nominate a candidate whose platform aligns with public opinion.

The presidential primary debates are the most direct source through which voters learn about candidates’ platforms and begin to discern between them. However, a debate’s effectiveness at providing voters with the tools to make well-informed choices is largely dependent upon the moderator. As John Hudak of Brookings points out, a debate’s efficacy in giving voters new information depends on the moderator’s willingness to assert themselves. A moderator who fails to ask effective follow-up questions, for example, allows the debate to become nothing but a platform to repeat candidates’ signatures promises. The 2020 presidential campaign, which will pit an idealistic Democratic Party against an incumbent president who has a tenuous relationship with the truth, needs debate moderators comfortable with challenging candidates on both factual claims and policy feasibility.

During the Democratic primary debates, moderators must be comfortable pushing candidates to consider the political realities that impact their ability to enact policy. When Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) references her ambitious higher education plan, for example, moderators should ask her how she would prioritize the components of the plan if not everything can get passed, what sorts of compromise plans she would support, and other detail-oriented questions. It is important that “voters know not simply the ideal policy a candidate supports, but what that candidate could tolerate to advance the cause for change,” as Hudak writes. Not only do these questions provide voters with information about the candidates’ stances on policies that are more likely to be passed, it also gives candidates an opportunity to demonstrate their policy knowledge.

In both the Democratic primary debates and during the general election debates, moderators need to be careful with how they fact check candidates. During the third Republican primary debate in 2016, moderators Carl Quintanilla, Becky Quick, and John Harwood aggressively questioned the feasibility of flat tax proposals, debt ceiling stability, and other promises, and the candidates on stage attacked them for it. Even when candidates are not directly antagonistic, it can be very difficult for moderators to effectively fact check. Politifact editor Angie Holan explains that “fact-checking in real-time is incredibly hard—you really need to know the material.” This explains why Candy Crowley’s effort to correct the record in a factual dispute between President Obama and Governor Romney in a 2012 general election debate “only added confusion to the exchange, making the moderator the story.” This is one of the reasons why Jim Lehrer and Bob Schieffer, who have moderated fifteen presidential debates between the two of them, both agree that moderators should not intrude on the debate in order to correct the record. Stories of failed fact-checking in the past contributes to the unwillingness to fact check candidates today.

What moderators can do, however, is a more indirect form of fact checking. David Uberti, writing for the Columbia Journalism Review, suggests that a “moderator could alert the audience that the issue has been thoroughly fact-checked at a news site listed at the bottom of the screen.” By flagging that others have researched the claim at question, the moderator encourages interested voters to determine the truth of the matter at hand. Additionally, highlighting the fact-checking website as the mechanism to resolve a fact dispute protects the moderator from appearing to be taking sides in the debate, helping them signal neutrality. Journalist Alan Schroeder summarizes that “all of this fact-checking at a very thorough level by journalists is going to be better than what a live moderator can do off the top of his head.” Neutral fact checking sites can cite transcripts, show video, and include other evidence to support the fact check in a way that a debate moderator simply cannot. It is essential that candidates cannot lie their way to the presidency, and indirect fact checking through a neutral group is the best mechanism to prevent that.

Presidential debates have the potential to provide voters with a set of information that they cannot find anywhere else, but this requires effective moderating. Moderators must focus on the political realities constraining candidates when they ask follow up questions so that voters are not disillusioned when progressive proposals from the Democratic primary debates cannot get through Congress. Additionally, while it is impossible for moderators to make sure that everything said during the debate is true, indirect fact-checking allows interested voters to determine for themselves whether the statements are true or not. This incentivizes candidates to tell the truth. Idealism can get candidates elected, but pragmatism gets policy passed; voters should have access to information about how candidates will react in both arenas.

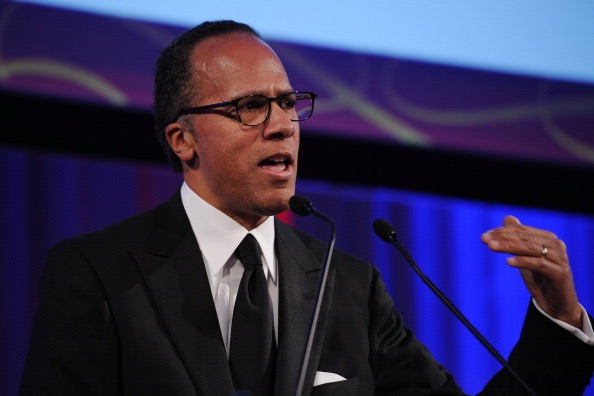

Photo: Lester Holt