‘Enemy’ of the State, ‘bonehead’ and ‘pathetic’ sit among many other pleasant terms that President Trump has used to describe Jerome Powell, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. While many view such aggressive comments as a departure from precedent, presidents have repeatedly clashed with the Fed since its founding in 1913. Recently, given rate cuts and hints of an impending recession, the world has been paying more attention to these attacks. Now more than ever should be the time to interrogate the exact relationship between these two figures, the President and the Chairman of the Fed. Unfortunately, there exists a deep-rooted power imbalance that falls far in the President’s favor.

The US government coordinates fiscal policy while the Federal Reserve has jurisdiction over monetary policy. Fiscal policy regards decisions over government spending and federal tax rates. Monetary policy involves methods of changing the interest rates to affect the money supply. Both can impact economic growth and inflation. So why let the Fed, an independent group who doesn’t answer to the government, control our money supply? Well, it turns out that leaving both monetary and fiscal policy in the hands of the President would be a very bad idea. And not just with our current President.

Short-term growth is almost always augmented by a decrease in interest rates. If the Fed cuts the Federal Funds Rate, it will reduce the interest rate at which banks lend to each other. Therefore, it would be easier to borrow; more businesses would invest in capital, and the average consumer would be more willing to buy, leading to economic expansion. This effect is more or less instantaneous: when the Fed meets every six weeks, they make a decision to hold, cut, or hike. Then after the meeting, the Fed publishes its target and starts buying or selling securities. Fiscal policy changes don’t materialize as quickly. Herein lies the problem. Any President looking for re-election wants a strong economy during election years, and the simplest mechanism for bringing about this change is a rate cut about a year or two before the ballots are cast. This is exactly where Trump is right now. Serving the political needs of the President, however, is precisely not the point of monetary policy.

In 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson wanted a rate cut so much that he “invited” the Chair of the Fed, William Martin, to his ranch and proceeded to “physically shove him around the room” while screaming at him for not caring about the soldiers in Vietnam. This came a few weeks after Martin had raised short-term interest rates. Next year Martin hiked the rates again. He didn’t do this because he hated Johnson or the soldiers in Vietnam. He did it because Johnson had been cutting tax rates, and enacting massive wartime spending. Had he not increased the rates, excessive inflation could have crippled the American economy – an effect that could far outlive Johnson’s presidency. Former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, in his memoir, also recalls Reagan’s chief of staff, James Baker, demanding outright that he not raise interest rates ahead of the 1984 election.

The most controversial of these encounters must be President Nixon and Fed Chairman Arthur Burns. Preceding his re-election in 1972, Nixon coerced Burns into lowering rates to help with the war effort. This was one of the many fascinating revelations of the Nixon Tapes. A while later, Burns called Nixon and said, “I wanted you to know that we lowered the discount rate… got it down to 4.5 percent”. Nixon replied, “Good, good, good”. It doesn’t take a lot of intuition to understand the cause for concern over this dialogue – the President should not be coercing an independent official for his political gain. Economists largely agreed that the conditions warranted rate hikes, rather than cuts: the US had just come out of a year of recession in which interest rates had been lowered dramatically, spending in Vietnam was still huge, and Nixon was facing dangerous levels of inflation. The American economy suffered from the inflationary effects of these cuts for another decade. Inflation crushes the middle class as nominal wage increases don’t keep up with the rising price of goods, cripples international trust in the dollar that appears to be unstable, and makes consumers hesitant to purchase out of fear of price changes.

Clearly, there is substantial discourse between President and Chairman that goes on behind closed doors. However, there are a few legitimate interactions between the two figures; most importantly, it is the President who nominates the Fed board members, who are then confirmed by a simple majority of the senate. It is incredibly rare that presidential nominees get rejected. Once elected, board members remain for fourteen years.

This arrangement leaves large loopholes of political abuse. If the President nominates the Fed members, they inherently ‘owe’ something to him. Not in a legal sense but definitely in a practical sense. Additionally, the President will likely nominate board members who sympathize with him. A lot of the criticism that surrounded Chairman Burns was that he was an avid Republican loyalist, and may care more about keeping a conservative ‘in town’ than possible fluctuations in the American economy.

Then there’s the most potent question of incentive and repercussion. Trump has repeatedly alluded to firing Powell if he doesn’t “get his act together,” or in other words, cut rates. The Federal Reserve Act denotes that the President may remove the Chairman “for cause”. This leaves the issue perfectly ambiguous. When Lyndon B. Johnson asked the Department of Justice if he could remove Martin, he was told that disagreements over policy were not a sufficient cause for removal, but different political conditions exist today. Extreme partisanship has prompted Congress to yield to the demands of their leader, rather than act as the representatives of their states and electorates. Even when Congress does stand up to the President, Trump hasn’t been afraid to ignore them. When he declared a national emergency for his great Southern wall, he illegally bypassed Congress. What’s to say he won’t do this again?

As I write, and as you read, Trump’s lawyers are working on the double to figure out a way to demote Powell without firing him. It seems unlikely that whatever plan his team conjures up will be truly in accordance with the law.

Americans should consider themselves very lucky if this current administration is not able to bludgeon the Fed into submission. More importantly, this issue’s recent attention must be harnessed to expedite legislative reform. Once nominated and confirmed, these Chairmen should be at the behest of Congress, not the President. Dismissal should be a matter of House and Senate majority. While members of Congress may share similar concerns for their re-election, this link is far more detached than that of a President who alone cares for his/her re-election and alone has the power of dismissal.

A more robust system under congressional jurisdiction would have two benefits. Firstly, it would inhibit the instability that we have witnessed under President Trump. Our current administration has ripped itself apart countless times as the President continues to exile officials who he appointed in the first place.

Secondly, it would reinstall the legitimacy of these roles, which are often roles intended to be removed from the central limelight of politics, but now feel subject to it from above. The end goal of government should be to serve the people who elected it, not those who constitute it.

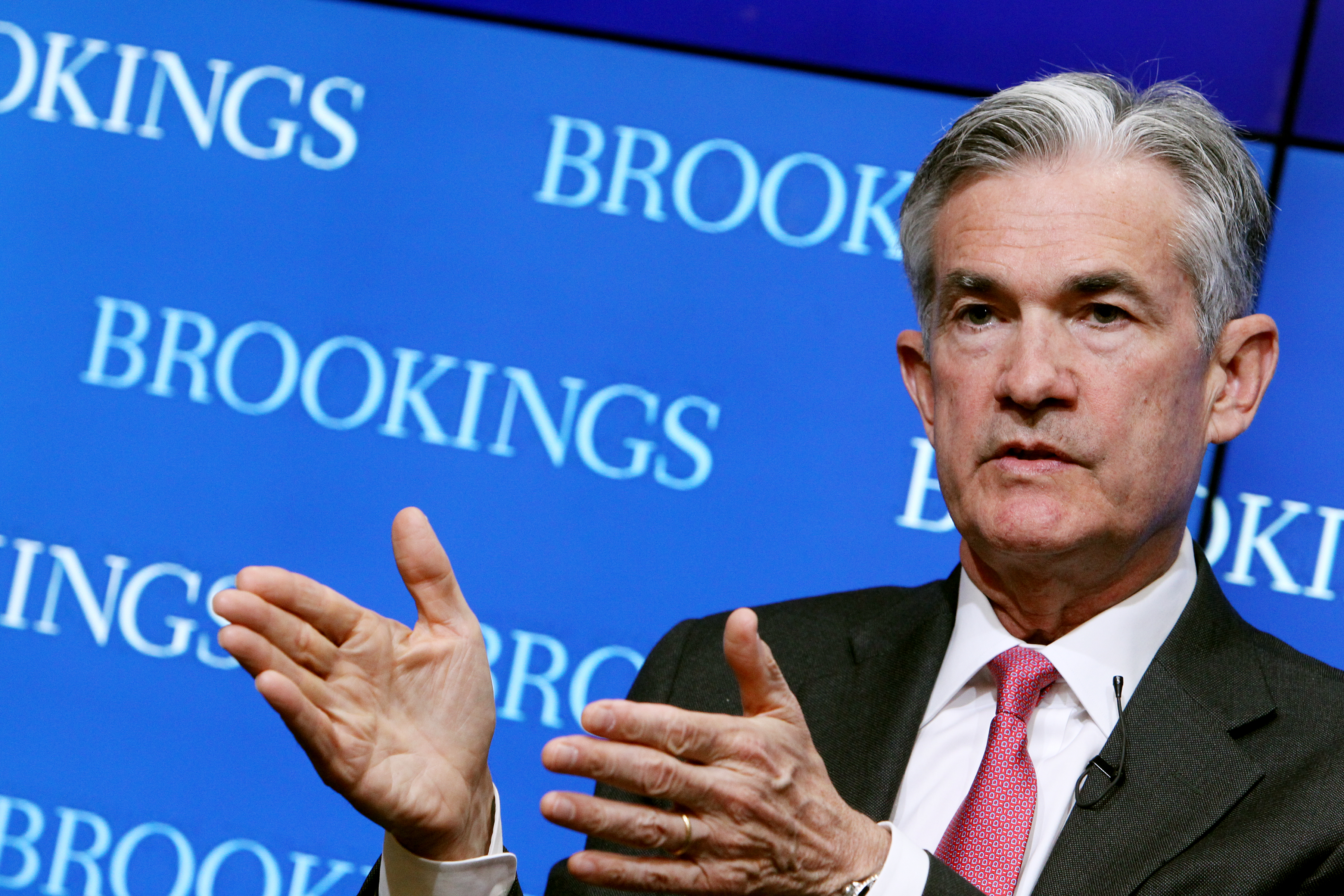

Photo: Image via Brookings (Flickr)