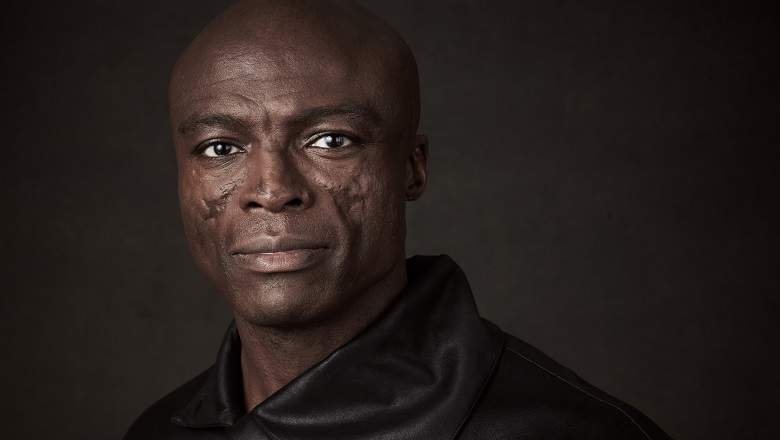

Seal Henry Olusegun Olumide Adeola Samuel, best known by his mononym Seal, is a singer and songwriter. Born in the United Kingdom and of Nigerian and Afro-Brazilian descent, Seal was raised by a foster family in Westminster, London until the age of four, was then returned to his biological family, and eventually left at 15. He obtained an associate degree in architecture then worked at various engineering and design jobs until leaving the field to pursue music full time in the mid 1980s. The multiplatinum and diamond artist has won four Grammys and been nominated for 14. In 1995 he won an MTV Video Music Award for his critically acclaimed single “Kiss From a Rose,” which spent 26 weeks on the charts, was featured in the motion picture Batman Forever, topped out at #1 on Billboard Hot 100, and won Grammys for Record of the Year and Song of the Year in 1996. Seal coached on The Voice AU in 2012, 2013 and 2017 and was a guest judge on America’s Got Talent season 12. In 2016 he performed in Tyler Perry’s live musical event The Passion on Fox. His most recent album, Standards, was nominated for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album at the 2019 Grammys. Seal is the father of four children with former wife Heidi Klum and currently lives in California.

Amelia Spalter: I hear you didn’t shake hands even before the pandemic. Did you know something we didn’t?

Seal: It was this meaningless, extremely unhygienic, pleasantry that I started to see as certainly a waste of my time. My initial reason for doing it was slightly different, though. I went through a period of self-realization two and a half to three years back. I felt that I was becoming more and more — I wouldn’t necessarily say reclusive — but certainly disconnected from people. Consequently, I was becoming disconnected from within, from myself. So I did this 180 as a retaliation to that. I decided I was the one who was going to instigate connections. One of the first steps to doing this was to just eliminate handshaking from my life and replace it with hugging.

It turned out to be quite disarming for people, but eventually they warmed to it. I said, “Look, I don’t shake hands, but I’ll hug all day.” If I’m spending time with someone, I want to connect. That is my agenda, even if it’s for ten seconds, I want to have a dialogue with you. I want to see you and I want you to see me. Let me be clear, it’s not like I all of a sudden turned into Mother Teresa or Florence Nightingale and was like, “You’ve got to hug the whole world.” It wasn’t that. Someone actually just perfectly summed up my reasons for hugging in a recent TED talk: “It’s much harder to hate someone up close.”

AS: You don’t text either, right? How do you pull that off as a professional musician, or as anyone living in 2020?

S: I detest texting on a social level. If it’s a work-related thing, then texting is fine. But socially, immediately the conversation starts with, “How are you,” right? You text back, “I’m great.” But I don’t give a shit about how you are. Because if I really cared how you are, I would call you up, right? Then it’s, “How are you doing, Amelia?” “Oh, I’m great, Seal! I had a great day at Brown today. I was crushing it and it was awesome,” and I go, “Chances are Amelia’s great,” right? Or if you go, “I’m great” [with a melancholy inflection], I go, “Really?” and you go, “Yeah, you know, honestly, Seal, on my way into school this morning I was at an intersection, and this person across from me almost caused an accident and then said something really offensive. It pissed me off and sent me on a bad trip. But in the grand scheme of things I’m okay, I guess.” Have I solved your problem? No, but what has happened is we have had real dialogue. I actually gave a shit about how you were doing. A problem aired is a problem halved. But what happens on a text? “Hey, Amelia, how you doing?” “Oh, I’m great.” “You’re great? Great.” I’m really already onto my agenda.

I’ve become known as the chronic FaceTimer — to the point where friends of mine have found it annoying. Do you know what my pet peeve is, above everything else? It’s somebody will text me, and I call them back, and they don’t pick up. It’s like, dude you just texted me, you obviously have time. But you don’t have time to actually engage in real dialogue, that’s what it is. The irony of it is, during this pandemic, guess what? Everyone’s available all of a sudden. You FaceTime someone and they’re like, “Yes, human life! Yes, hi! I’m here!” Suddenly everyone’s available for FaceTime all the time. I love it.

AS: What do you think the most profound impact of COVID-19 will be on the music industry?

S: Where music is concerned, our tolerance threshold will come way down. Because a lot of the misogynistic bullshit only works within a certain kind of arena, when you can be out and about in the clubs, or maybe at a festival, where the artist can generate a level of frenzy and get people all hyped up on what my producer calls whizzbangness. A lot of that stuff’s existence is predicated on it.

Putting it bluntly, now shit’s just got real. More people will be asking, “What are you saying?” You know, “Yeah, yeah, I heard what you said, but what are you saying? What are you trying to say? What are you telling me that is going to make my life better? Is it going to be bling this and bang that, or are you actually saying something that is relevant to me? What are you singing about? Why should I be listening to your music?” I saw an artist who shall remain nameless post a new video yesterday, and it was just more… much of a muchness. It was more of the same thing. Honestly, the video just made me go, “Has anyone actually watched the news about what’s going on at the moment, or am I dreaming?” I just don’t see how anyone is not sensitive to the social climate. People are hurting right now. There are people losing their jobs, losing their loved ones, people whose lives are in tatters.

Historically, whenever there’s been a period like this, it is the arts, painting, filmmaking, and music most specifically, that have always been the great communicators. The arts are the fabric that draws everyone together, the great medium that brings about solidarity and gives people the hope and ability to transcend difficult times. So people are going to be questioning what you create more so now. Those people who have been affected, who want relief, are not trying to hear about, “My gold watch this and my car that and my ass this and this bullshit that.” They’re going to want to hear that it’s going to be okay, that it’s going to be tough, but you are not alone. And by the way, you’re not alone. I see you. We will get through this together. We have been through worse, and ultimately, we will prevail.

AS: Where does music for escapism fit into that?

S: I’m not saying that everything has to be its own I Have a Dream speech. I’m not saying that everything has to be deep and meaningful. It just has to not be misogynistic or reckless. Take an artist like Ed Sheeran, for example. There’s a reason why Ed Sheeran can stand on a stage with an acoustic guitar and play Wembley Stadium, which has a capacity of about 80,000 people, three nights in a row. Is Ed Sheeran my favorite artist? No, I don’t own a single Ed Sheeran record. But he’s a hell of a songwriter. He touches millions of people. Why? Because you can strip everything away from Ed Sheeran, it wouldn’t matter, all he needs to do what he does is a guitar and his voice. He deals in the constant.

I divide music up into two groups, the variables and the constants. There are lots of the variables, lots of them. There are things like genre, the beat, the other sounds that are used, whether they’re machines or whether they’re instruments, the fashion that goes along with all that. Those are the variables. There are lots more of them. The constants, there are only two, and they don’t change by definition of their name: the song and the voice. They do not change throughout history. Ed Sheeran stands up there and is able to fill Wembley Stadium to capacity on multiple consecutive nights. Why? Because he writes great songs, and he sings his ass off, and he’s convincing. One of the things to come [from the pandemic], it will filter out a lot of the noise. People are going to be much more prudent with the ways they invest their time. They will be looking more towards the things which communicate with them in ways that make a difference in their lives.

AS: You’ve talked about performing as existing in an almost incorporeal state. Has it always been that way?

S: Music has always been a spiritual experience for me. The first time I ever performed was at a PTA [Parent-Teacher Association] event when I was 11 years old. My parents had never heard me. My teacher was a singer, and I wanted to be just like him. He called me on the stage to sing a Johnny Nash song, and I remember it being the scariest moment of my life. I closed my eyes, sang the song, and at the end of it everyone clapped. My parents were just shocked. And it turned from the scariest place in the world to the most welcoming place. I never forgot that feeling. It was a spiritual feeling. It was healing. It transcended the physical and became more of a cathartic balm or elixir for my spirit, for my soul. Music has always had that. I think that’s been my MO, because I don’t know any other way, for better or worse.

AS: Does it ever feel as pure as it did that very first time?

S: Yes. I always know when I’m on the right track. When I’m writing something and I well up with tears, that’s when I know.

AS: You’ve studied Christianity, Buddhism, and astrology. Do you see music as the fourth line item in that list, or something separate?

S: I’ve often described music as being the one thing that saved me. Having come from a fairly traumatic childhood, music has always been my salvation. It’s always been that friend. You know, we just talked about the perils of loneliness and the ensuing tragedy of being alone. Well, I have been lucky in that ever since I discovered music, I’ve always had that to turn to. She’s always been that friend, that ear that has listened, always. I’ve never felt that I was completely abandoned. Well that’s not entirely true, but for the intents and purposes of this conversation, I haven’t, because music has been so cathartic for me. I just assumed at an early age that that was the “why” behind music. Not necessarily what it would do, but why it would do. Why do I sing? Why do I have a voice? Why does it connect with people? And I always assumed that that was why. That one was meant to offer that same relief, give that same compassion, and make that same connection available for everyone else. I guess my songs reflect that. They have been less religious and more allegorical, offering an account of life as I’ve been experiencing it. The older I get, I’ve come to understand it’s not all that different from anyone else’s, to be honest.

AS: You just talked about music as a she. Do you feel music, as a concept, skews more feminine?

S: It feels more feminine, music, because it’s so sympathetic and so nurturing and so maternal and so loving. Not adjectives I would generally use to describe a man.

AS: What are some of your most unexpected sources of inspiration?

S: I find myself doing things that stop me from focusing on music, because I have to be so engaged, like snowboarding. I’m a huge snowboarding junkie and have been for many years. Specifically, heliboarding, being dropped on a summit [out of a helicopter], things like that. The reason I love those things is because I don’t hear music when I’m doing them. I’m so focused on trying not to die that I don’t hear music. I hear music all the time. Sounds that are just sounds to other people tend to have a cadence and a rhythm to me. I have a bicycle bell that is tuned to E, so I think, “Oh, it’s E,” rather than it just being a bell. When I’m engaged in cycling, or something extreme like heliboarding, those are times when I don’t think of music. I find times when I don’t hear music are actually are quite inspiring, because they tend to have a residual effect. When I have not been concentrating on music, it allows me a kind of objectivity to a particular song or awareness to a particular subject that then finds its way into a melody.

AS: When did you first notice that you heard music all the time?

S: It’s just for as long as I can remember. It’s like, when did you realize that you breathe all the time? I can’t imagine life not like this.

AS: As someone who has been very open about his own struggles with anxiety in the past, what advice do you have for people dealing with similar mental health conditions now?

S: We cannot do this alone. We cannot get, nor are we meant to get, through this alone. Trauma is generally caused by more than one person, and therefore you need more than one person to heal it. There is no shame in, and it is not a sign of weakness to talk with people and ask for help. It’s the opposite, it’s a sign of courage and it’s a sign of strength. Understand that although you are special, you are not unique. This is a common experience and a shared one. I’m not saying that everyone suffers from anxiety or panic, but what I am saying is that next time you’re in the street looking at people, take a close look, and you’ll see that we all have our shit. Everyone is going through something. The key to all of this is solidarity and communication, and the way we do that is through connection. Over the course of dealing with my own demons, I have had to go get help. So reach out to someone and ask for help. The worst they can say is no, and I have a feeling they won’t say that. But if that person doesn’t help you, reach out to somebody else. Show them strength through vulnerability. It is not a weakness to be vulnerable, it is extremely courageous.

AS: Frankly, I’m happy to hear you got some help, because in 1991 you had major success with the release of your first album, which went quadruple platinum… but immediately afterwards you got double pneumonia, were in a car crash, and then had a friend shot and killed directly next to you. How did you keep from fearing success at that point, let alone sustain the energy to further the momentum of your career?

S: I’ve always tried to look at things in perspective. Everything is always changing and no condition is permanent. Look at all the good things that come with success, however challenging it has been from time to time. Look at all the things that I am able to do. And yeah, sometimes it is difficult to see it that way. Even though I kind of sing about looking at things in isolation by staying in the moment. Songs like “Prayer for the Dying,” there’s always an air of optimism. I always look towards a brighter day. I do think it’s important to have that, but it’s not something I do consciously. Maybe it’s a result of my childhood. Maybe I had no option as a child, maybe I kind of kept trying to get back to the garden, or I kept trying to get back home, so to speak. Maybe that’s why.

AS: Did the trauma of being surrendered to foster care in early childhood make the constant rejection of the music industry seem trivial by comparison?

S: No, no, no, quite the opposite. Being placed with a foster family was my saving grace because they were very loving. Very, very, very loving. For all intents and purposes in the formative years, they were my family. And I had nothing but wonderful memories. Those were actually the best memories of my childhood. Everything after [I was returned to my birth family] sort of got real, from the age of four to around 15 when I ran away from home. There were nice moments in it, but speaking honestly, those formative first four years, those were wonderful. If it hadn’t been for my foster family, I think I could have repeated the cycle of abuse and doom and destruction, because I wouldn’t have known any better. My years with my foster parents served as my salvation because in the ensuing challenges that came after leaving them, they were like my barometer. They were almost more like my home. It was always, “Okay, I went from this situation where it was all nice and fluffy to this situation where it’s shitty, and I’ve got to somehow get back to where I was before.” That guided my moral compass.

AS: As countries begin to open up, do you think things are actually returning back to normal?

S: There will be those who will emerge from this and see it all as a kind of a bad dream, but the vast majority of us are changing as we speak, for the better. I’m not by any chance meaning to come off as insensitive to those people who have suffered loss and are hurting right now. I can best speak from my perspective, though, and I think the vast majority will emerge from this better, brighter, stronger, more compassionate and more awake. Why do I say that? Other than the fact that I’m an optimist, I say that because I think we’re going to be here for a minute. In fact, I think we’re going to be here for a while. I don’t believe all of a sudden this is going to be over and within a couple of months stadiums are going to be packed or anything like that.

Because of that, we will have the time to really get deep into it and go address some of the issues that lie within. We will each have the opportunity to go and look for the person that we’ve abandoned. When we find that person, we will have to figure out whether we like that person. Chances are we don’t, if we abandoned them. And those of us who don’t like that person will have to figure out how we can get back to liking them again. By “that person,” of course, I am talking about the self. Those of us who have abandoned that inner child and reinvented ourselves for a better life in a better world will have to go looking for that person and figure out how we can love them again. That’s ultimately where the change, the rebirth, will come from. Because we have been forced to sit down and go inward. I hasten to add, as I said before, the key is that we don’t have to do this alone. We mustn’t do it alone even if we could. I certainly can’t. So I think we’ll be here for a minute, and ultimately, it will be a good thing.

AS: What do you sing in the shower?

S: I was just singing a tune that I was going to do something with. I came up with a melody in the shower today and I forgot it, but my theory is that if it is any good, it will re-emerge.

AS: You are known for surprising fans with songs, but I have a feeling you don’t need a camera present to compel you. What’s your favorite spontaneous performance that not as many people know about?

S: I do like doing that. I remember one time, when my second album came out, I was in a hotel in New York with a friend. We were walking down a corridor and somebody was blaring my album in one of the hotel rooms. They were just going at it, having some kind of party. I knocked on the door and started singing along with my album. And they were really stoned. The guy was going, “Hey Jessica, come to the door!” She was like, “What? No, you come here.” He’s going, “No! No! Come to the door!” They were so high that I mostly did it to mess with them, so then when the song finished, I just walked away. I just left. The look on their faces… That was funny.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.