In a recent message addressing an organizing drive at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, President Joe Biden came out strongly in favor of the right of workers to organize, stating emphatically that “unions built the middle class” and warning employers that there should be “no coercion.” Biden’s statement was one of the strongest pro-union statements ever given by a sitting president and signaled a 180 in the White House position on labor relations from the Trump administration. Trump appointees to the National Labor Relations Board notably launched a sustained offensive against the right to organize. However, even accounting for the Biden administration’s support, the labor movement has reached its lowest point in decades. As union membership continues to decline and employers develop increasingly sophisticated methods to suppress organizing drives, it is important to consider the policy changes that can reverse the trend of declining worker power. Sectoral bargaining is one of these changes, with broad implications for pay, benefits, and the dignity of workers.

In 2020, only 12.1 percent of workers were represented by a union, a number which drops to 6.3 percent when only workers in the private sector are considered. It is not a coincidence that this decline in union membership has coincided with rising income inequality and stagnating real wages, as studies have indeed found that unionized workers receive higher wages, known as the “union wage premium.” However, the United States’ system of labor relations, as established by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), exacerbates the problems that lead to declining union membership. The NLRA establishes a system of “enterprise-level bargaining,” in which the entity with which the union negotiates is the “employer unit, craft unit, plant unit, or subdivision thereof.” This system is the form of collective bargaining that Americans are most familiar with: a union organizes the workers at a particular factory, workplace, or business, and then bargains with the management of that business for a contract.

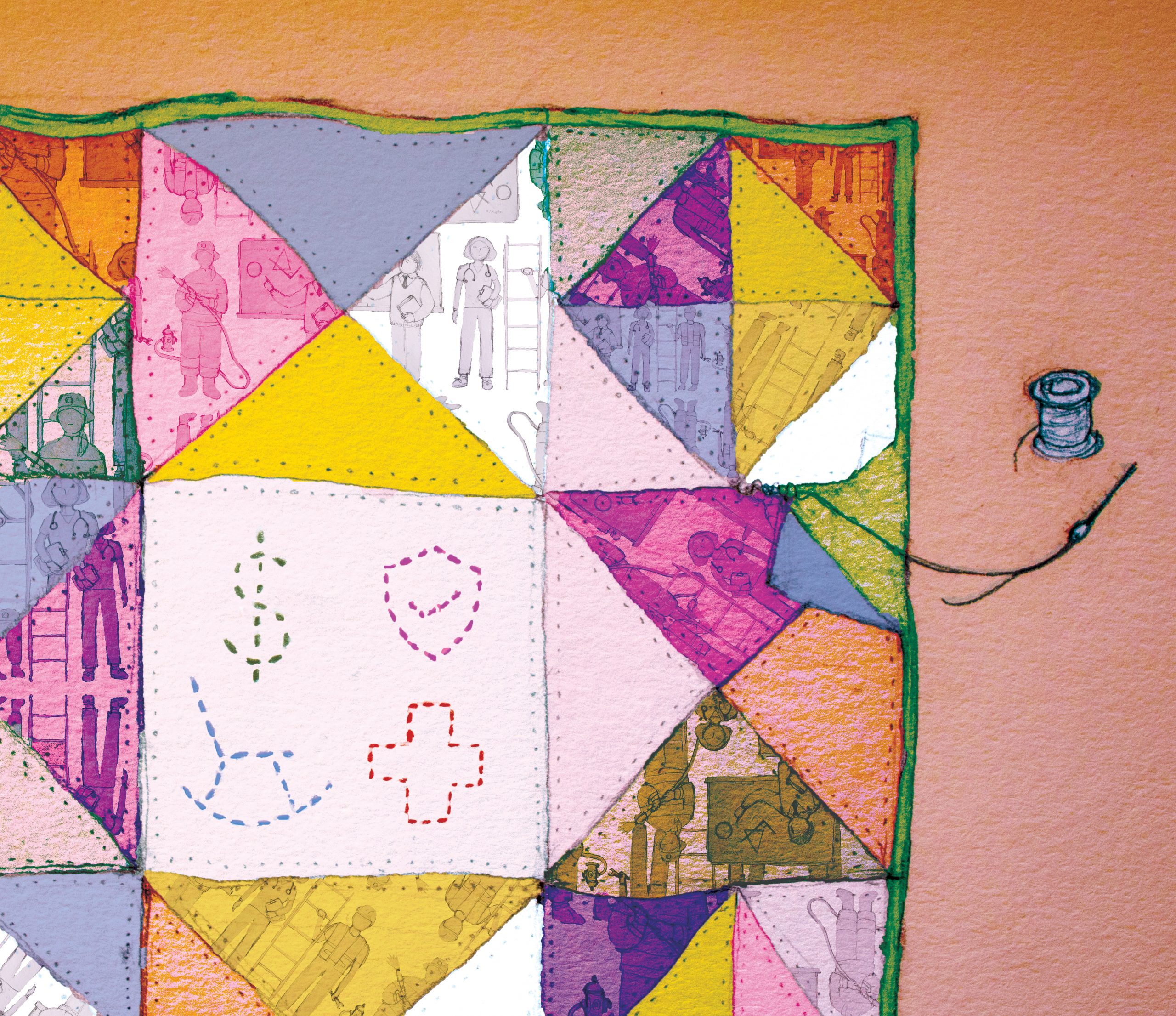

The NLRA and the enterprise model of union organization it inspired create a patchwork of union coverage in which employees who perform identical tasks receive wildly different pay and benefits. Depending on their employer, workers at unionized workplaces receive the full benefits of union membership while those at non-unionized workplaces do not. In addition, the enterprise-based model incentivizes firms to fight unionization tooth and nail. The reason is simple: if employers expect unionization to raise their labor costs relative to their non-unionized competitors, they will attempt to prevent unionization drives through any means, including by violating labor laws. One report found that employers are charged with violating federal law in an astonishing 41.5 percent of union election campaigns, and that 20 percent of union election campaigns include a charge that a worker was illegally fired for organizing. Even when employers do not violate the law, anti-union campaigns are common, with companies such as Amazon using surveillance algorithms to predict and suppress organizing drives. These anti-union tendencies further suppress union membership, exacerbating the existing downward trend. Breaking the cycle of declining union participation and employer subversion will require a rethinking of the systems that govern American labor relations.

Sectoral collective bargaining stands in sharp contrast to the enterprise-based system described above. Under sectoral bargaining, workers do not form unions and negotiate contracts with individual firms. Instead, unions negotiate contracts with employer representatives and local governments, whose terms then apply to all workers within a given sector. Instead of workers at one restaurant receiving the benefits of union representation while the others do not, all restaurant workers within the area will receive the same benefits from this contract, regardless of the union status of their workplace. The idea is not a new one: Sweden, Denmark, and France all implement some form of sectoral bargaining. Denmark in particular is notable: its famous $22 an hour wage for McDonald’s workers is the result of a sectoral bargaining agreement between employers and unions. These countries are also notable for their high levels of union participation: in Denmark approximately 67 percent of workers are in a labor union.

While some may resist sectoral bargaining as forcing workers into union-bargained contracts, sectoral bargaining empowers workers by ensuring pay and benefits for workers in the sector who are not union members. In Denmark, while only 67 percent of workers are in a union, 83 percent of workers are covered by a collective bargaining agreement due to sectoral bargaining. By implementing sectoral bargaining, Denmark extends the benefits of unionization to a wider swath of the workforce than would be possible under enterprise-level bargaining alone. Sectoral bargaining also removes many of the incentives for firms to fight unionization: if all of the workers at a firm’s competitors receive the same benefits and pay due to a sector-wide collective bargaining agreement, the firm has less reason to prohibit workers from organizing. One paper finds that more centralized collective bargaining systems, such as sectoral systems, result in lower employer opposition to unions, confirming this idea. In these ways, sectoral bargaining can both extend the benefits of unionization to large groups of workers and check the anti-union activities of employers, potentially revitalizing the American labor movement. This feature of sectoral bargaining can make it more palatable to conservatives, as they prefer cooperative labor relations to the adversarial model promoted by enterprise-based bargaining. Notably, along with prominent Democrats Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, sectoral bargaining has been endorsed by conservatives Oren Cass and Marco Rubio as promoting good relations between workers and employers.

Implementing sectoral bargaining will not be easy. The American system has functioned on an enterprise-based model for decades since the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, and switching to a nationwide sectoral bargaining model will require significant new legislation. However, local governments can and should experiment with establishing regional wage boards, which set wage standards based on input from union representatives, employer representatives, and local government officials and can function similarly to true sectoral bargaining. These wage boards are already possible under existing law in California, Colorado, and New Jersey, and these states could potentially lead the way in bringing sectoral bargaining to America. Doing so would prove the viability of sectoral bargaining, and perhaps finally begin to reverse decades of declining labor power and bring about a new era of strong unions and secure workers.

Original illustration: Sophie Foulkes