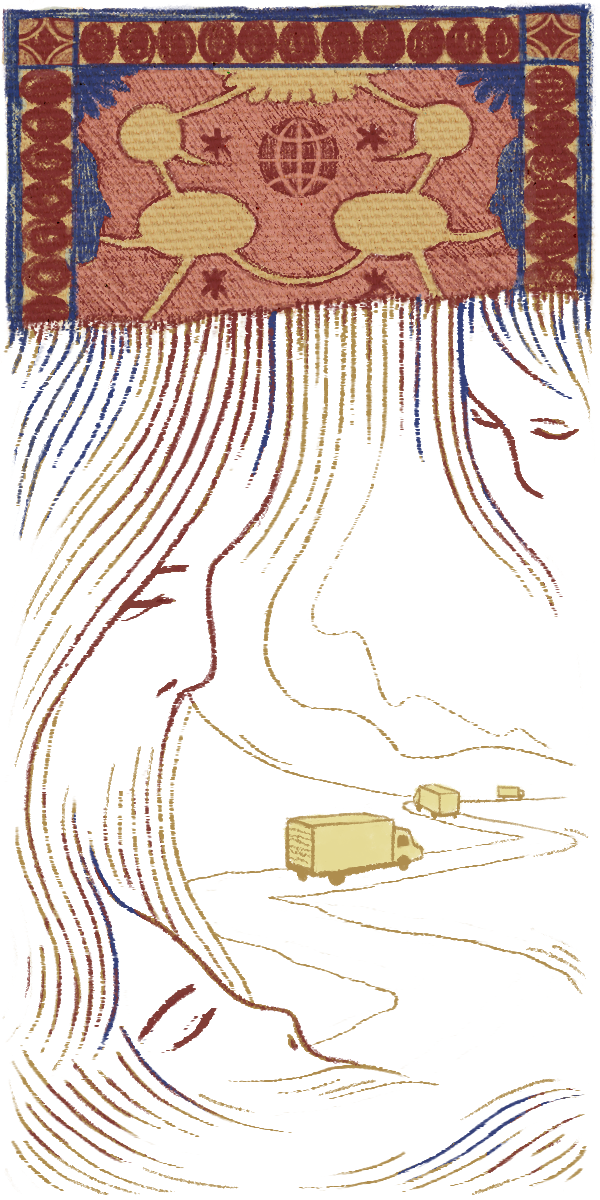

Persian rugs have long been seen as an international symbol of luxury, beauty, and ancient culture. In fact, the earliest-known Persian carpet dates back to the fifth century BC, but the process of their creation has remained relatively unchanged over time. Even today, traditional hand-woven carpets require months—sometimes years—of back-breaking labor over looms, and the preparation of materials required for the process is just as meticulous. In fact, nomadic shepherds from the Qashqai tribe and the Bakhtiari tribe herd over a million sheep to source the raw material. The subsequent dyeing process has been lauded as sustainable and natural; the yarns are colored using pigment from insects and plants, such as eucalyptus leaves, indigo, turmeric, and pomegranate peels. Still using no machinery, the wool is then boiled for several days and left to air dry in the cool Iranian winds. Only a select group of nomadic tribal peoples retain the rare skills required in the next step: turning the tough, fibrous wool into thread that will eventually form the thousands of knots needed to weave a traditional Persian rug.

This complex and labor-intensive practice of Persian rug-making is mainly performed by tribal women, oftentimes in their own homes. However, the money that comes out of this lucrative industry often falls into the hands of middle-men instead of those of the original artists. These Persian rug-makers are not simply farmers or factory workers easily replaced with machines; rather, they are artists with intergenerational indigenous knowledge and creativity. They must be compensated as such.

Though the immoral practice of underpaying rural workers is common around the world, initiatives to protect farmers and factory-workers have been on the rise in recent years. Consumers are increasingly turning away from fast fashion, looking for “Fair Trade Certified” produce, and valuing the “conflict-free” verification in diamonds and gemstones. Yet movements like these do not include Iranian indigenous women, despite the intensive labor and creative skill required to produce their product. Traditional Gabbeh rugs from the Fars province of Iran are often designed without any premeditated specifications, as the rug-makers are trusted to improvise new versions of traditional motifs.

Only those growing up with the art form can develop the keen eye and skilled hands needed for this practice. Nonetheless, market forces allow these artists to be treated as unskilled workers, and rug prices are determined according to the size and material of a rug, rather than the complexity of its design or the hours of labor required to make it. In other fields, like the gemstone or food industries, this logic makes sense; the bigger the diamond, or the larger net weight of produce picked, the higher the price. With rug-making, however, it is not the size or material of the carpet, but the artist’s time, creative intuition, and expert hand that are most special. An analogous situation would be pricing the Mona Lisa based on its materials or the size of its canvas, rather than by the value of the time and expertise that da Vinci dedicated to the piece. Though clearly unjust, this devaluation of artisanship is a real, pressing issue for Iranian rug-makers.

If artisanal skills continue to be undervalued and rugs continue to be priced based on this flawed metric, the industry may soon die out. The Persian rug industry is already dwindling as younger generations, having witnessed the low returns of such high-cost labor, are deterred from learning the art. Moreover, the demand for handmade rugs is decreasing as buyers turn to purchasing cheaper, factory-made rugs from China and India. Demand has also decreased because of the crippling sanctions introduced following the Trump administration’s withdrawal from Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran. Now, with international financial transactions limited by banks, tourists who visit hoping to purchase a fine rug are required to pay only in cash, making them less likely to buy at all. This issue is only exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has halted most leisure-related travel and makes relying on in-person purchases from tourists all the more risky.

An estimated five million Iranians are connected to the production and distribution of the some 400 tons of homemade rugs produced per year in Iran, around 80 percent of which are exported. Given the importance of the rug industry to Iran’s economy and the timeless beauty of the art form, the rug-makers at the center of production should be protected with a measure similar to the aforementioned “Fair Trade” and “conflict-free” movements. Due to the rug-makers’ special position as artists, they can leverage their work in a way that farmers and factory-workers in other industries cannot: Their creative intuition and artistic eye is irreplicable by a machine. Instead of allowing middle-men to arbitrarily mark up the prices of rugs and hold onto the profits, a new protection should guarantee that the creator is recognized for her labor and for her artistic ability. A new metric must be introduced to accomplish this goal, wherein the time and artistic complexity required of the worker is what counts, rather than only the material or size of the rug. If the artists are allowed to indicate how long their piece took them and how difficult the design was to make, they can begin to receive fair compensation for their labor and skill.