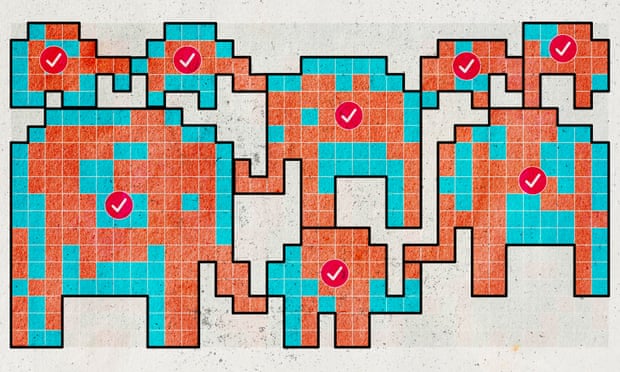

A decade ago, Republicans swept the 2010 midterm elections, flipping 63 House seats and a staggering 720 state legislative seats across the country. Using their newfound power, the GOP enacted ruthless gerrymanders—congressional and legislative district maps drawn to favor their party—with scientific precision, cementing their control over national and state legislative bodies for the next 10 years. As the post-2020 redistricting process began, Democrats braced themselves for another decade in the political wilderness. A vigorous effort to win control of key state legislatures in the 2020 election had fallen short, leaving the GOP in complete control of redistricting in 21 states. Democrats only controlled eight.

All but four states have now approved new congressional maps, and the cartographic doomsday that Democrats so anxiously anticipated has largely failed to materialize. New maps created 10 additional Democratic-leaning districts, nearly eroding Republicans’ structural advantage in the House of Representatives. For Democrats, this begs the question: What went right? Luck certainly had something to do with it. Courts intervened in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina to stymie state Republicans from pursuing their most grotesque attempts to gerrymander district maps. But Democrats were proactive too. In Illinois, Nevada, Oregon, New Mexico, and New York—though New York’s maps are currently facing litigation—Democratic-controlled legislatures eliminated a total of 12 Republican districts, enacting aggressive gerrymandering campaigns of their own. The political calculus was simple: Take the Republican playbook and use it against them. And—at least in the short run—it worked.

This marks, at the very least, a shift in tone for the party. In the wake of the post-2010 redistricting process, most Democratic leaders spent the better part of a decade railing against gerrymandering as undemocratic and unconstitutional. After flipping the House of Representatives in 2018, the first bill Democratic lawmakers introduced was an election reform package that would—among other things—ban partisan gerrymandering. In many states, Democrats advocated for creating independent redistricting commissions, which would redraw constituency boundaries without political motive. But that was then, and this is now. In the face of escalating illiberalism and authoritarianism within the Republican Party, many Democrats have forsaken high-minded good-governance for a new approach—proportionate response. Gone are the days of Michelle Obama’s lofty axiom “when they go low, we go high.” Today’s Democratic Party has, by and large, embraced Eric Holder’s caustic transposition: “When they go low, we kick them.”

Though Holder’s rhetoric is extreme—and in many ways runs counter to the kind of messaging Democrats have historically embraced—it underscores a fundamental truth in modern American politics: The Republican Party has abandoned any pretense of commitment to democratic governance. The stakes of partisan politics now transcend ideology. If Democrats hope to preserve American democracy, they cannot sit idly while it is undone.

Critics have been quick to point out the apparent hypocrisy of this rhetorical and strategic reversal. And they are not wrong. The savage gerrymanders enacted by New York and Illinois’s Democratic legislators completely contradict the values the party espoused just a few years ago. Many party officials are well aware of this but remain unfazed. The chair of the Colorado Democratic Party, Morgan Carroll explained why to The Atlantic: “As a matter of policy, I think we should pursue [independent commissions]…. But as a matter of politics, if across the country every Dem. is for independent commissions and every Republican is aggressively gerrymandering maps, then the outcome is still a Republican takeover of the United States of America with a modern Republican Party that is fundamentally authoritarian and antidemocratic. And that’s not good for the country.”

The antidemocratic turn of the Republican Party has been long in the making. In 2013, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder. In the following years, Republicans have imposed draconian voting restrictions, specifically targeting minority communities. Congressional Republicans have unanimously blocked any Democratic efforts to protect the right to vote or end the practice of partisan gerrymandering. And in 2020, the GOP engaged in a concerted effort to overturn the results of the presidential election, culminating in the seditious and deadly January 6 Capitol riot. In the wake of the insurrection, the party has only plunged further into authoritarianism.

Democrats face a stark reality, with no good options. While responding with gerrymandered maps in their favor might be politically advantageous, this response further erodes democratic norms. But should they stick to their purported values by pursuing independent commissions and fair maps, they will effectively allow an unabashedly illiberal Republican Party to win power.

This debate is not confined to redistricting as questions over abolition of the Senate filibuster and expansion of the Supreme Court have become central to the Democratic Party’s internal discourse. Opponents of such measures cite the possibility of a cycle of escalation. As Senator Angus King (I-ME) explained, “I’m skeptical of [court expansion] because I don’t know where it stops. You could end up with a 100-person Supreme Court that changes every four years.” Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) argued that these drastic reforms would cause irreparable harm to US institutions, leaving them more vulnerable to political volatility. Others, like freshman Representative Mondaire Jones, have pushed back, contending that institutions, including the Court, have already been ensnared by the winds of political turbulence.

At its core, this is not a debate about whether the Democratic Party should veer in a more moderate or progressive direction, but rather a question of how seriously it is willing to take the genuine threat the Republican Party poses to American democracy and if it will come to accept that the institutions we are taught to revere are fundamentally broken. Senator King’s fears of a cycle of continuing escalation are already a reality. It is simply a one-sided cycle, as one party hurdles toward authoritarianism, while the other maintains the illusion of a now-vanished status quo.

Democrats’ pursuit of their own aggressive gerrymanders this year has produced something of a political anomaly: a national congressional map that is, in essence, fair. A nearly equal number of seats lean toward Democrats and Republicans, leaving neither party with an inherent advantage. At the state level, each party has effectively disenfranchised the other’s voters, denying individual communities representation; nationally, each party is fairly represented.

There is no way for Democrats to actively defuse the fraught polarization that has engulfed American politics. But entrée into the realm of proportionate response has thus far yielded a more democratic electoral landscape than the United States has seen in decades. Filibuster abolition and court packing, though they may later be used against Democratic priorities, would undoubtedly produce political outcomes that better represent the will of the electorate.

The reluctance to engage in such tactics is understandable: It means coming to terms with the failures of the institutions we are taught to venerate. But what we value in our institutions is the ideals they purport to represent—and our institutions are a means of actualizing those values.

For a decade, Democrats tried to “go high” as Republicans “went low.” It failed. If Democrats hope to preserve American democracy—and maintain any hope of winning power again—they need to try something new.