According to the Migrants’ Files, over 23,000 migrants died trying to reach Europe between 2000 and 2013 — a number so staggering that Russia Today called the Mediterranean an “underwater graveyard.” Illegal entry into the continent, especially through Italy, has long been a contentious issue on a national and European level, but civil unrest in the Middle East and ongoing instability in many North African nations have recently led thousands more to leave their homes in search of safety. More than 100,000 people have landed in Italy this year — a significant increase from just 43,000 in 2013. Among these are immigrants in search of financial security and refugees escaping from the horrors of civil war, persecution and violence.

In response to the increasing number of shipwrecks that have followed this wave of immigration, the Italian Marine Corps created a rescue initiative called Mare Nostrum, or Our Sea. This program was approved under Italy’s left-wing government in October 2013 after the death of over 350 migrants who tried to reach Lampedusa, Italy’s southernmost point, which has become the new symbol of Italian immigration since the incident. The initiative aims to avoid such casualties by intervening in dangerous passages and taking incoming immigrants to detention centers. The government then arrests the people who brought them, making the journey into the country safer for migrants but riskier for traffickers.

As a key entry point into the rest of Europe, Italy is the focus of continental reform efforts, but the country is not braving the waters alone. After a recent summit meeting between Italy’s Minister of the Interior, Angelino Alfano, and the European Union’s Commissioner for Home Affairs, Cecilia Malmström, Italy has finally prompted the EU to take responsibility for the border crisis. The new pact comes after years of mostly unilateral Italian efforts to both stem the tide of immigration and ensure safe passage for those involved. The Italian marines, for example, have been patrolling the Strait of Sicily since 2004 in an attempt to catch traffickers. Since October 2013, the marines have reportedly saved — and subsequently detained — about 100,000 people. They’ve done so not only by surveying the coasts of Italy, but also by navigating past Italy’s own territorial waters to look for vehicles transporting immigrants to the country’s shores. The incursion of Italian forces past their official national boundaries has long suggested the need for more international efforts, but the EU has criticized Italian practices for their ineffectiveness and denounced the disgraceful conditions of Italian detention facilities, which The New York Times described as “inhumane, inefficient and costly.” As a result, European officials have avoided any direct involvement with Italy’s program and have, up until now, mostly left immigration policy and practices to the EU’s member countries.

Given the rapidly expanding number of refugees seeking asylum, the EU has had to reconsider this stance. Following the new pact, the EU will soon deploy Frontex Plus, its border control agency, to monitor the Italian border and devise future immigration policy. But while Frontex Plus is partially modeled after Mare Nostrum — at least in terms of its role in patrolling the seas — Alfano reiterated that the new initiative is not “a photocopy with a name change.” Frontex Plus has very different aims, as it has promised to shift Italy’s priorities from limiting immigrant casualties to protecting Europe’s borders. While the extra help may come as a relief to Italy, which considered Mare Nostrum to be only a temporary, emergency response, it comes at a significant devaluation of the lives of immigrants and refugees.

Founded in 1999 to oversee border protection projects, Frontex Plus has been tasked with protecting Europe’s maritime border on the Mediterranean. But the organization’s goal to secure and protect the border, unlike Mare Nostrum’s goal of protecting and saving immigrants, is worryingly narrow in scope. If there is an emergency outside the border, Frontex Plus will extend no rescue party. While the EU maintains that Frontex Plus strengthens the Italian effort, it will maintain the burden on the Italian government to go outside its territorial waters in emergency situations. As such, Frontex Plus is advantageous only in the sense that it could serve as a first step towards future policy reform in the EU; the way the program is framed today and the aims it has set are disappointing. Cloaked under the rhetoric of a stable initiative, the EU’s decision only superficially addresses the crisis at hand and robs asylum seekers of a consolidated safety net during their crossing.

The ultimate effect of the EU’s policy shift will depend on how Frontex and Mare Nostrum work together — and there already seems to be disagreement about practicalities. Although Malmström has remarked that Frontex Plus will only serve to reinforce Italy’s actions, Alfano has stated that the country will retire Mare Nostrum this November. This uncertainty regarding control of waters and delegation of responsibilities is further proof of the EU’s inability to effectively implement multilateral plans. It also suggests the unwillingness of its members to shoulder the burden of immigration or to even acknowledge it as an issue to be solved by the European community at large.

There is no unified European structure for dealing with the influx of asylum seekers, and countries have no obligation to grant residency — even to people who have successfully applied for legal status in other member states. Meanwhile, the number of individuals seeking asylum has surged in the past year, especially as a result of the Syrian civil war. While it is true that the continent cannot possibly integrate and absorb all the immigrants seeking refuge, the EU member states have extremely inconsistent policies on granting asylum, making the overall process confusing and unreliable for those seeking security. John Dalhuisen of Amnesty International has called European actions against the crisis in the Mediterranean “shameful.” Many members of the EU, including Italy, maintain a quota on refugees that blocks asylum seekers from finding safety on Europe’s shores. Because of the 2003 Dublin III Regulation mandates, which state that the first country in which immigrants request asylum must handle and accommodate the immigrant, there is no way for even those refugees who do receive asylum to move around Europe as other Europeans do. International channels for refugee redistribution simply do not exist — a problem for those who often do not want to remain in debt-stricken Southern Europe, but who also cannot apply for legal status in a different country. The efforts of humanitarian campaigns such as Mare Nostrum, with all its flaws, are seriously hindered if there is no willingness within the EU to create a multilateral agreement on refugees.

Further complicating the potential for a sustainable and enduring policy on immigration is the fact that the entire debate has been framed with alarmist rhetoric: Immigrants are increasingly portrayed as an economic and social threat to stability. In Italy, this has been a fundamental talking point in right-wing politics for years. With the rise of anti-communitarian pessimism, such groups have gained traction in national constituencies and increased their influence in Brussels. In Italy, only a minority actually holds these extreme beliefs on immigration, but the right certainly leans towards isolationism. The Lega Nord, one of Italy’s most conservative right-wing parties, ran a campaign in 2010 depicting a Native American with the caption: “They suffered immigration and now they live in reservations!” Alfano himself has talked about keeping immigrants from stealing Italian jobs.

This line of argument is deeply flawed. Many economists and think tanks agree that immigrants do not drive down wages or jobs, and historical data has often shown that unemployment actually decreases during periods of high migration. More importantly, the moral implications of the EU’s immigration policy on thousands of helpless refugees should take priority. In 2011, illegal immigration and related policies cost Italy only 2.07 percent of national expenditure. The issue is less about how much money is being spent, but rather about how it is being utilized. In the same year, Italy spent approximately €124 million ($156.9 million USD) on immigrant integration projects, but almost double that amount on trying to keep immigrants out. By pouring money into unsustainable prevention measures, Italy will only exacerbate the dire situation for refugees while wasting taxpayer euros.

In Italy, there is a deep-rooted idea that projects such as Mare Nostrum actually incentivize illegal immigration. However, immigrants who choose to make the trip to Italy often do so as a last resort and not necessarily with the expectation of assistance. Radical anti-immigrant movements like Beppe Grillo’s Five Stars Movement and the more moderate right have repeated misinformation. But European inaction, combined with the plight of Middle Eastern immigrants, means that immigration is an issue that is unlikely to go away soon. As a result, these political movements will have to either moderate their views or be ignored — presuming Italy doesn’t want to have death on its doorstep.

Although effective national immigration policy is important, it is only truly viable if EU member states work together on multilateral reforms. As the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has advocated, there needs to be an agreement on mobility for immigrants and refugees similar to the one made for European residents. Although this maneuver will involve ceding some border authority, it would also help redistribute migratory fluxes to all regions of the continent and mitigate any unfair burdens on one nation. Furthermore, there needs to be a shift in policy from the politics of protectionism to one of sympathy and integration. Everyone agrees that Europe cannot shoulder the entire burden of immigration and asylum seekers, but if it intends to be a leader in equitable treatment of civilians, the continent must take concrete steps towards saving immigrants from the immediate danger of their journeys.

Until the EU revisits its responsibility to protect the well-being of immigrants, there will be no effective solution to the immigration issue. Emergency programs and militarized borders will not stop people from fleeing civil wars; they will only inflict further loss of life. It does not make sense to create only reactionary policies, which ultimately permit traffickers to take advantage of human suffering. With Frontex Plus, the EU is choosing to patch up a problem instead of creating the sustainable solution: a continental approach to immigration and internal corridors for integration.

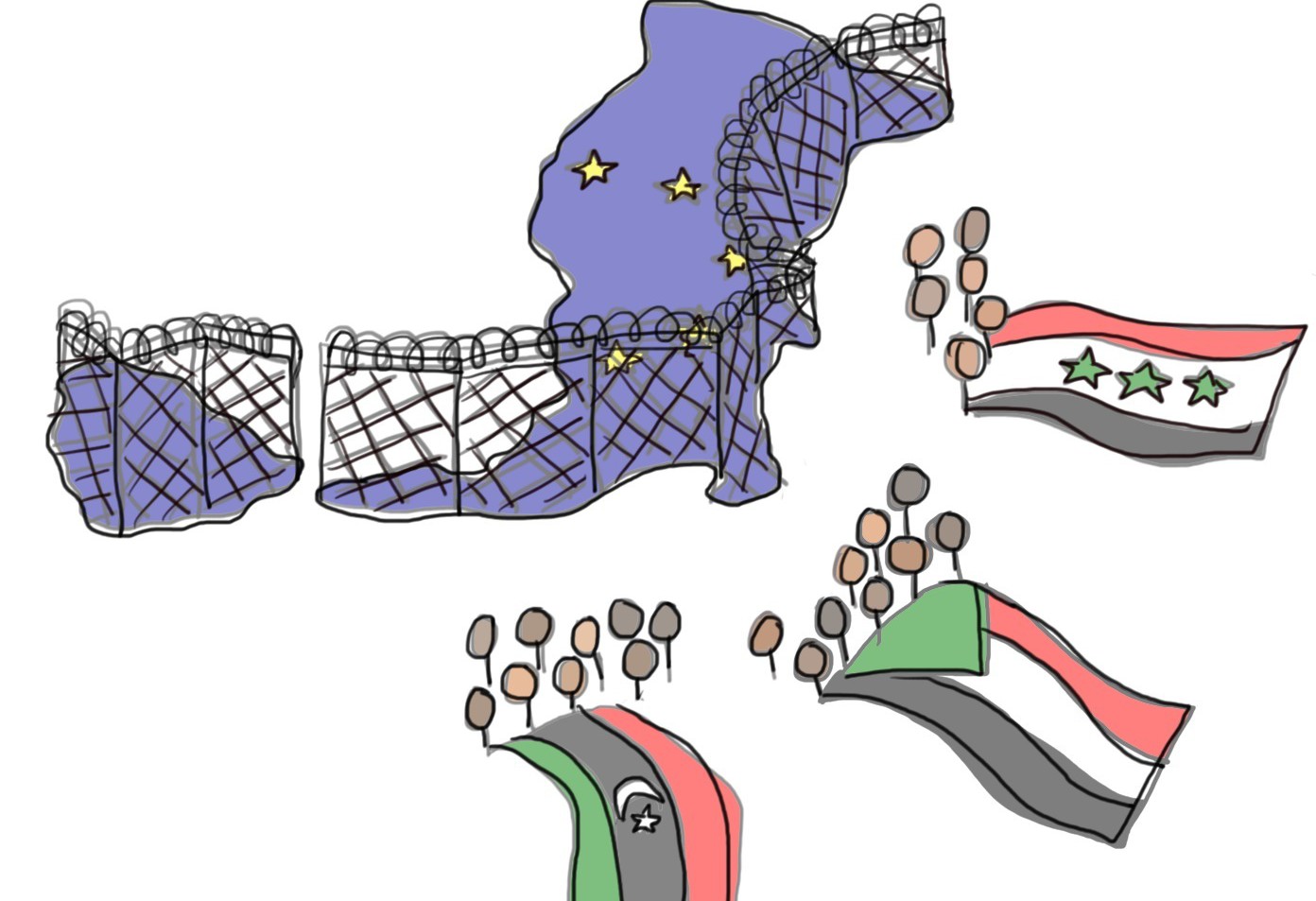

Art by Kristine Mar.