Khabib Nurmagomedov has wrestled and defeated his fair share of bears since his first ursine tussle at age nine. It’s not particularly shocking, then, that he’s also an Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) Lightweight Champion and one of the greatest fighters of his generation. Nurmagomedov comes from a rich martial arts tradition in Russia, where even President Vladimir Putin claims to be a judo expert. But zoom into the vastness of the largest country in the world, and a more interesting trend emerges.

Nurmagomedov hails from the Russian Republic of Dagestan, a predominantly Muslim territory nestled between the Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea. Dagestan is known for its stunning natural beauty and, until very recently, for violent religious and ethnic conflict. The recent de-escalation of conflict can be attributed to the adoption of a novel exercise-based strategy that stresses discipline, recreation, and Dagestani pride. This strategy, which seeks to divert aggression into productive wrestling training, is used to prevent young men from entering “the Forest,” as the Islamic insurgency is known in Dagestan. Today, it has proven effective: Dagestan leads the Caucasus region in driving down religious violence.

Before diving into the implications of such a strategy, it is important to understand how it relates to the region’s historical context. While Dagestan is known for the strength of its UFC fighters, neighboring Chechnya gained international notoriety in the late 1990s for its brutal Islamist terrorist cells. In 1991, Chechen insurgents declared independence from Russia and invaded Dagestan with broad support from the Muslim populations of both Republics, kick-starting the Second Chechen War between the separatists and pro-Russian forces. This conflict was an especially brutal one in the region’s history, taking the lives of tens of thousands of soldiers, insurgents, and civilians.

For Chechnya and Dagestan, the roots of this war trace back all the way to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The Chechen and Dagestani separatists were fighting for their very way of life, an identity independent from the interests of Moscow and Putin. Both territories sought recognition and visibility in a world in which they felt smothered by Eastern Orthodox Russia. Yet when Russian forces finally quelled the

fighting and the separatist movement in 2009, these similarities between Chechnya and Dagestan faded. In fact, to safeguard Russia’s control over Chechnya, Putin installed Ramzan Kadyrov as its president. Since then, Kadyrov has been accused of a variety of human rights abuses associated with the implementation of his ultra-conservative agenda. The imprisonments, assassinations, and oppressive measures that define his brand are not expected to end anytime soon.

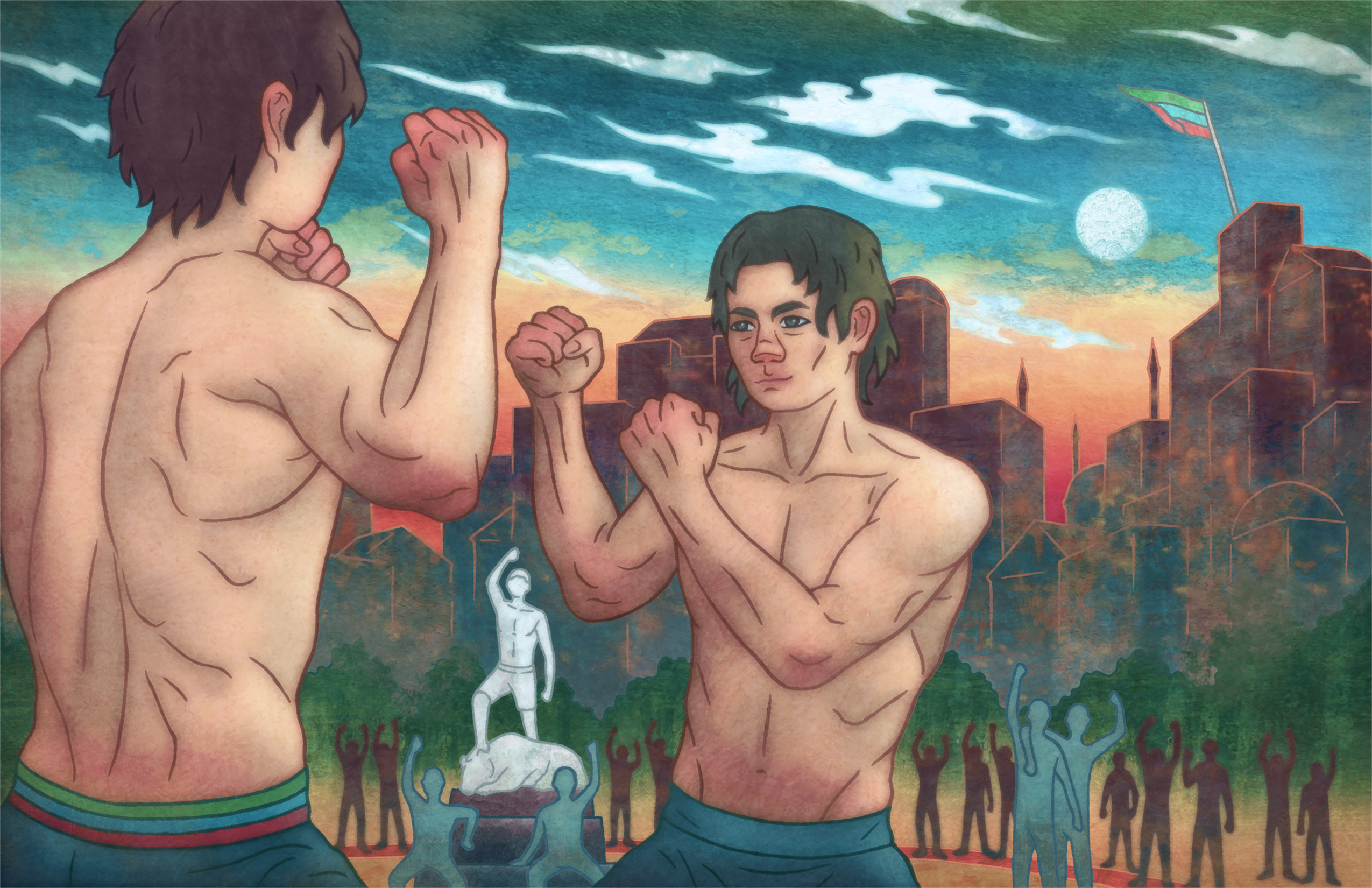

In Dagestan, however, the government and society at large have followed a completely different route. Perhaps due to its status as a more peripheral region in the war, Dagestan was spared from most of the purges and mass arrests that became the norm in Chechnya. Instead, the Republic transformed what it did best—wrestling and fighting—from recreation into an outlet for its young men. A quick walk in the capital city of Makhachkala reveals a huge number of open-air training grounds painted with slogans recommending “the Olympic gold instead of terrorism” or “discipline in the face of extremism.” But these words aren’t just for show. The boys begin and end each school day by grappling and exercising, occupying every square inch of these outdoor gyms.

All that’s required for boys to succeed in the sport is discipline so, naturally, all boys in Dagestan grow up with the dream of becoming like Nurmagomedov. This yearning for recognition was also a key driver of the war. Before the hostilities, Dagestan’s only heroes were the rebellious Cossacks of ages long past, who ultimately became the inspiration for many insurgents, the bulk of whom were poor and rural young men. Now, Dagestani wrestlers and Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters regularly grace the screens of international television. Having collectively accrued more than ten Olympic gold medals, they serve as heroes to the same young men who might have otherwise idolized combat fighters. Thus, martial arts have enabled Dagestanis to strive toward recognition and acceptance—the two desires that precipitated the violence of the past—without going to war.

Strikingly, beyond a few isolated incidents of violence in the past few years, ethnic and religious conflict in Dagestan is conspicuously low. Boys are increasingly choosing the singlet instead of the Kalashnikov. As far as strategies for dissuading boys from engaging in dangerous violence go, this one is particularly constructive. Instead of the secret prisons in Chechnya, maybe adopting a seemingly simple strategy like sports for children could help to redirect anger over ethnic and religious tensions. And what’s the downside? At the very least, they’re getting a good workout.