Fifty-five decibels. That is as loud as the room got when American chess wunderkind Bobby Fischer took on the Soviet chess machine Boris Spassky on July 11, 1972 in Reykjavik, Iceland. Officials began monitoring the hall’s sound levels when Fischer threatened to walk out of the “match of the century” if they did not remove all cameras—with a match this important, there was no room for error. Fischer argued that the cameras were noisy and contained mind-controlling devices aimed at disrupting his play. As ludicrous as this claim may seem now, it was not an unreasonable accusation given the backdrop of high-stakes US-Soviet geopolitical tensions. As the Cold War thawed toward détente, chess became an outlet for competition between the Soviet Union and United States.

Fischer’s claims made clear that these games were not so much about the individual players but about the flags they bore: Spassky and Fischer were nothing more than pawns in a geopolitical battle, and they were acutely aware of it. Fischer took the championship. Though he refused a ticker-tape parade and the key to his native New York City, he was rewarded with a City Hall reception. He also earned the admiration of millions of Americans who swept into hobby shops in droves to buy up chessboards.

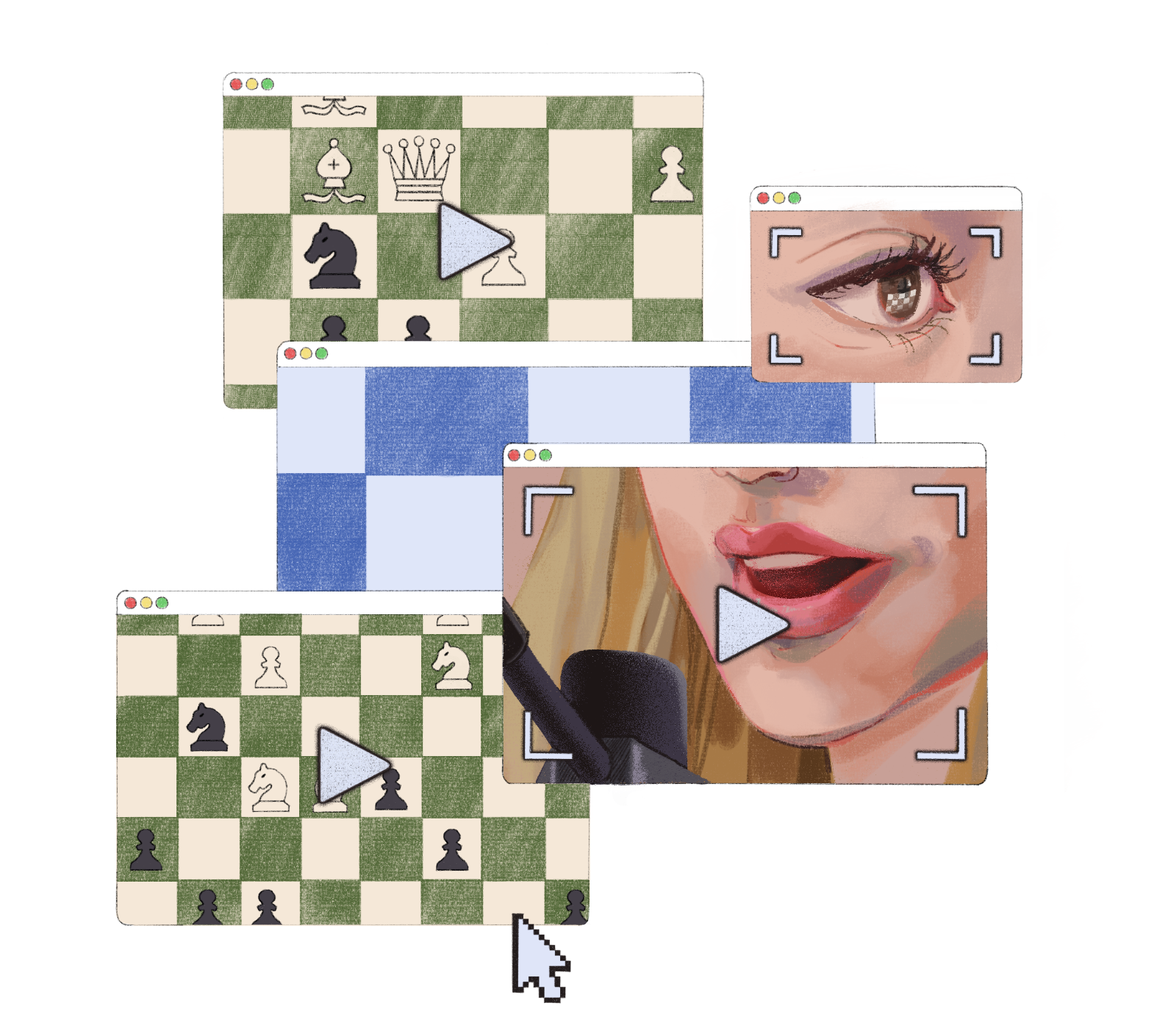

Fast-forward 50 years, the geopolitical chessboard has shifted seismically—along with the game itself. While many players still pore over Sicilian Defenses and Queen’s Gambits, a new crop of masters has taken center stage—and they do not operate like Spassky and Fischer. They are 20-something-year-old YouTubers, Twitch streamers, and TikTokers who also happen to be 2,000+ rated chess experts. Their social media virality, and thus their success, is predicated as much on their personalities as it is on their chess proficiency. These players, and the media they publish, have democratized chess, throwing off its yoke of nationalism. Playing everyone from relative newbies in Kiruna, Sweden to the infamous hustlers in New York City’s Union Square, Gen Z chess masters have literally changed the game. By taking chess out of stuffy hotel halls and meeting people where they are—in public parks, on the streets, or in digital arenas—this generation is creating new openings for anyone, anywhere to play.

When Anna Cramling sits down on the grass just outside the Eiffel Tower, mounts a chessboard on a cardboard box, and holds up a sign offering 20 euros to anyone who can beat her, she is not staging the match of the century. But she will get views—a million of them on YouTube alone. Three opponents take her up on her offer. One is a local fan of her videos, another is a novice tourist from Iowa. Although all three face a swift defeat, they know that the opportunity to play a top-ranked player is itself a coup. But the fact that a million viewers clicked on a thumbnail to find out how Anna checkmated them all—that is a cultural phenomenon. And a game open to anyone, anywhere—watched potentially by everyone, everywhere—has no need for national champions.

This new world order of chess may seem like a game-over for traditional, in-person competition. Shedding their national hero capes, even old-school grandmasters such as Magnus Carlsen, Hikaru Nakamura, and Anish Giri are building a social media presence. They now Twitch stream and post YouTube videos of in-person and digital matches against the likes of Cramling. If state affiliation is losing significance for players and fans at the center of institutional competitive chess, then perhaps what appears to be a radical break from old-school chess is not radical at all. Could it be more evolutionary than revolutionary? The rules remain unchanged from their origins in the 16th century: a zero-sum game between two people, moving with the intention to win, where sacrifices often serve the greater good. Black versus white. And this lends itself to the theater of heroism: Any pawn can become a powerful queen, and any king can fall.

This novel stage is just as suited to content creators angling for a monetizable, girl-beats-world narrative arc as it is to nation-states looking to strut their superiority. One of Cramling’s most viewed videos features the young, blonde Swede taking on trash-talking men who call her “darling” and tell her she’s “too easy” and that they “have to let [her] win.” Of course, most do not even stand a chance: She is too good. With two grandmaster parents and a 2,100+ Elo rating herself, she gives her audience something to celebrate: a young woman with no nationalist ax to grind, checkmating her way to triumphs of girlboss good over evil. Even when Anna plays Magnus Carlsen, she holds her own for six minutes, getting the typically reserved current World Chess Champion to sacrifice a compliment: “You’re doing a little too well for my liking.” With over 10 million views and 9,100 comments (on the Carlsen video alone), audience members have a clear message for Anna: She is their hero.

Chess is consummately mythopoetic, providing the game board on which heroic geopolitical and sociocultural battles alike could be structured and played out within their respective spaces and times. But as much as these narratives may share a common lineage, something is different. In the domain of the digital native where anyone can play, anyone can win, anyone can get a rating (via Chess.com), and any game can be broadcast to millions of people who can watch it anywhere, the center cannot hold. For this reason alone, content displaces country as country decouples from competition.

The geopolitical becomes the egopolitical as content becomes the new king. The era of patriots gathering around the flagpole to support their country and national chess hero may be eroding fast in favor of a new era of fans, followers, and subscribers from around the world all eager to know what their favorite content creator is up to next. Whereas chess as geopolitical sport relied on a fan base grounded in national identity, chess as egopolitical sport is unrestricted: Fans can be found anywhere and can find cultural affinity in their love both of the game and the content creator telling a story about it.

The evolution of chess is certainly not the first cultural phenomenon to test the permeability of national borders, and it will not be the last. Widely considered the “great equalizer,” technology is accelerating globalization and paving the way for people everywhere—regardless of country of origin—to contribute to the global culture and economy. But if the evolution of chess has anything new to say about globalization, it might be this: What breaks down geopolitical barriers and binds us together is not the win or the loss, or even how we play the game, but the stories we tell as we play it. Chess may well be teaching us that, as citizens of a globalizing world, we have more in common than we know; and while that might mean a checkmate for Fischer-Spassky-style rivalry, it is a better game for all of us.