Many say that the United States is in a “new cold war” with China. These two global superpowers exert their influence internationally through their webs of allies and large economies. The dynamics of Sino-American competition are heavily shaped by the relationships both powers have with large regional powers across the globe that make for lucrative trading partners. All eyes are therefore on India, which boasts the world’s largest population and one of its largest economies.

India has toed the line between these two states to its benefit, often opting for neutral policies. Even though India is a democracy, it hasn’t fully bought into the alliance of democratic states that shapes the West. On international political issues that pit the West against Russia and China, like the War in Ukraine or the Uyghur human rights crisis, India has consistently stayed neutral. The United States might appear to be a more appealing partner, given its military reach in the Indian Ocean, but China’s technology exports are vital for India.

By analyzing trade data of India’s imports and exports from 2005 to 2023, we can better understand the dynamics of Sino-American economic competition, as well as how Indo-American and Indo-Chinese relations have changed over time. The data shows that economic competition has increased over the last few years, but that there will be no clear winner or loser. This is because the United States and China fulfill different roles within the Indian economy: The United States is an importer of Indian goods, while China is a significant exporter to India.

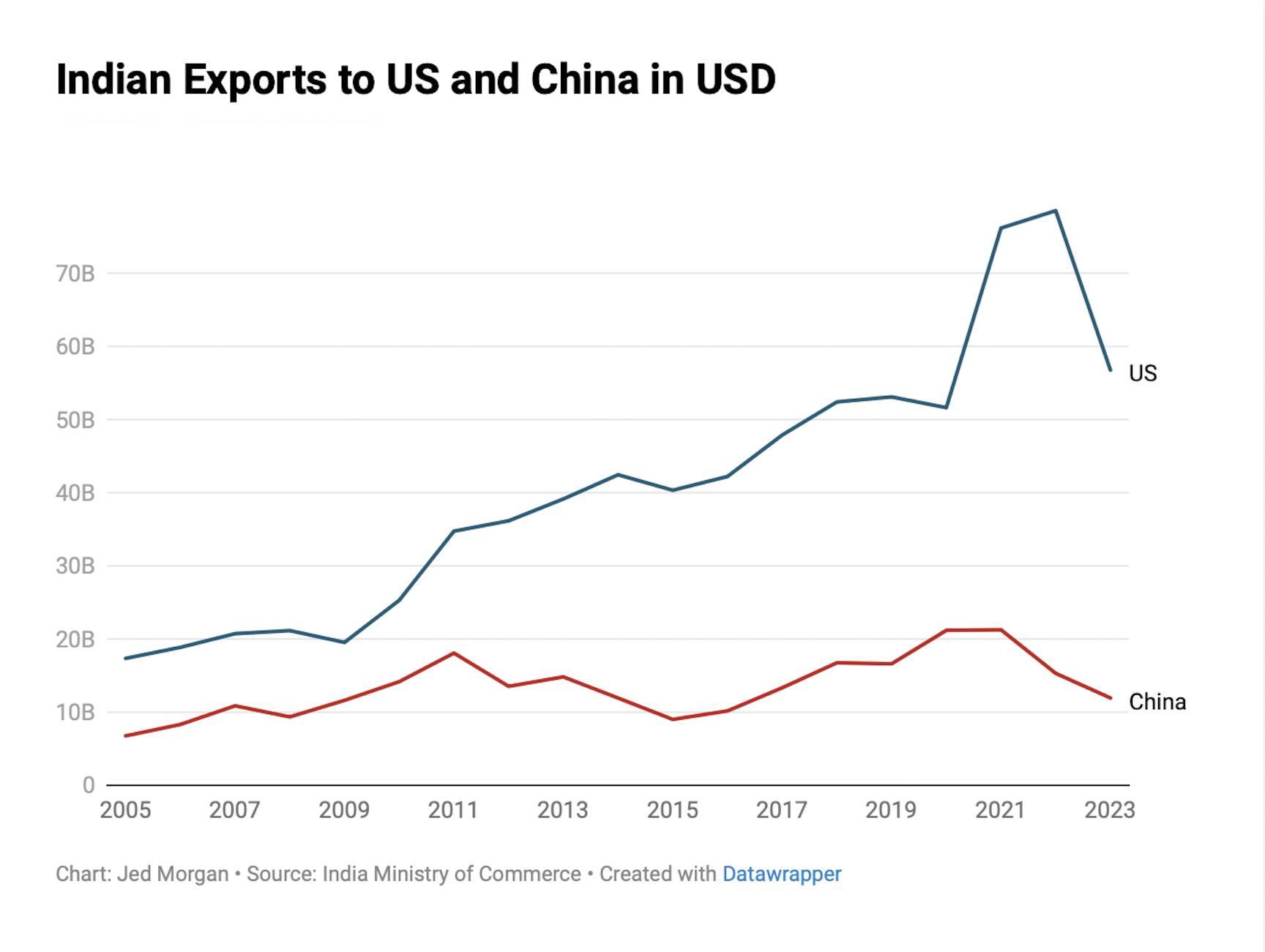

India’s Ministry of Commerce data shows that the 2023 share of Indian exports to the United States and China has remained relatively similar to 2005 levels. Between 2005 and 2010, there was a significant decrease in the share of exports to the United States—largely due to a dramatic increase in Indian exports to the UAE. However, this increase may be partially inflated due to reimportation and reexportation of diamonds and other metals, as an Economic and Weekly Review article found. The United States has dramatically increased its quantity of imports from India, while China’s imports from India have increased slowly over the past 20 years.

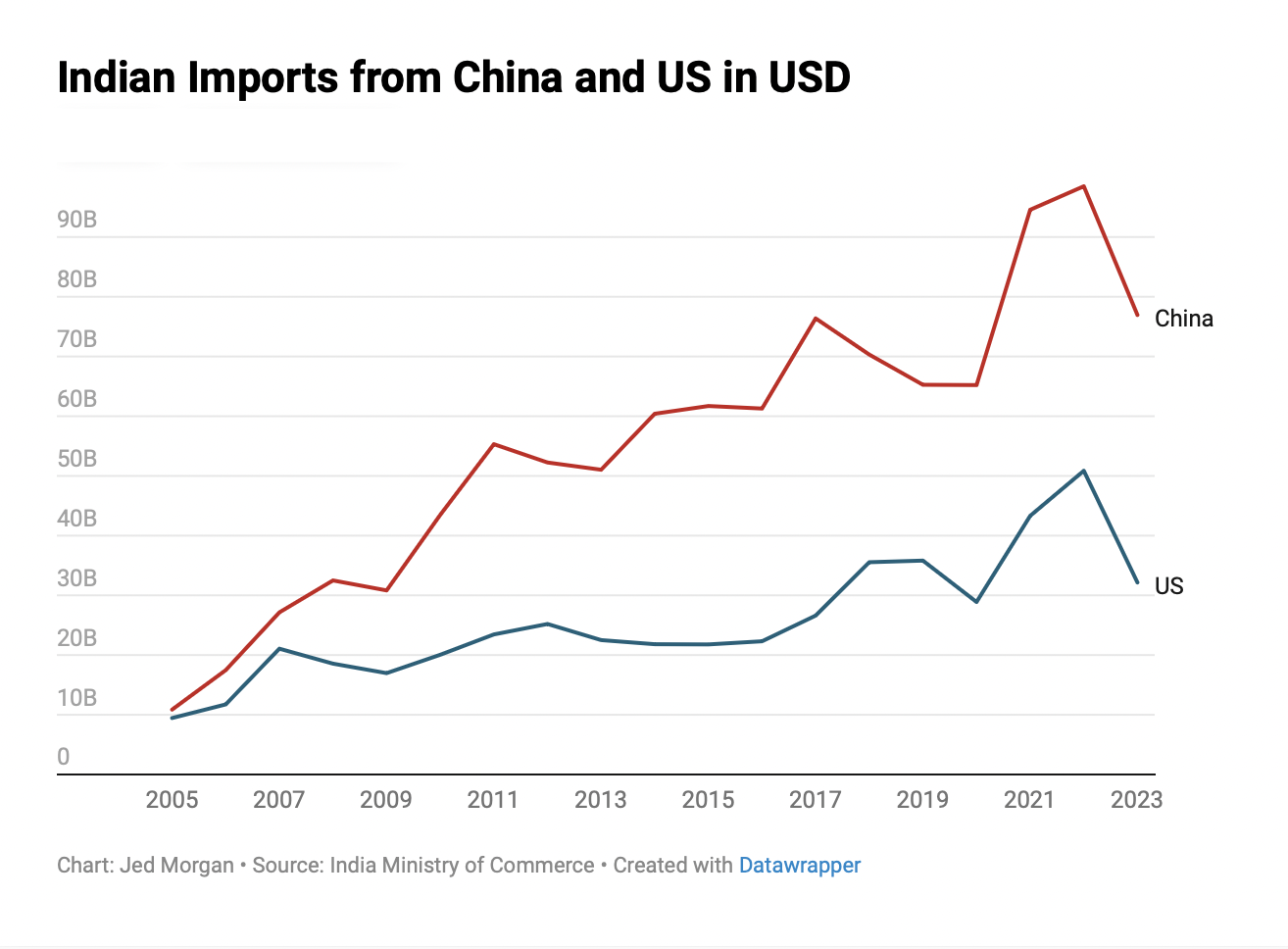

China is an increasingly important exporter to India, as its share of total Indian imports has doubled since 2005. The difference between American and Chinese exports to India grew from just one percentage point in 2005 to nine percentage points in 2023. The quantity of American and Chinese exports followed a similar pattern over the past decade, as the gap between the two has widened.

Notably, the United States has not increased its share of Indian imports, while China has received only a small share of Indian exports since 2005. The United States import share stayed at around six percent of India’s exports. China’s average share of Indian exports, meanwhile, decreased by three percentage points since 2005. This shows that while the United States and China have increased their share of imports and exports, respectively, of Indian goods, they have largely stuck to their niche. That being said, the amount of United States exports to India amounted to roughly $32 billion in 2023, while Chinese imports from India are just shy of $12 billion over the same period. The United States has successfully maintained a higher volume than China in its trade with India so far, but this may not last much longer. While the United States’ share of India’s imports has remained constant since 2005, China’s share of imports has increased dramatically. China could even the playing field in the future by continuing to solidify itself as India’s main exporter.

Since the United States and China fulfill different roles in the Indian economy, India will want to keep both superpowers close and to continue its neutral stance. India is also a beneficiary of economic competition between the United States and China, as it can extract more favorable terms from both states. New Delhi likely hopes to extend this competition into the future as its economy develops.

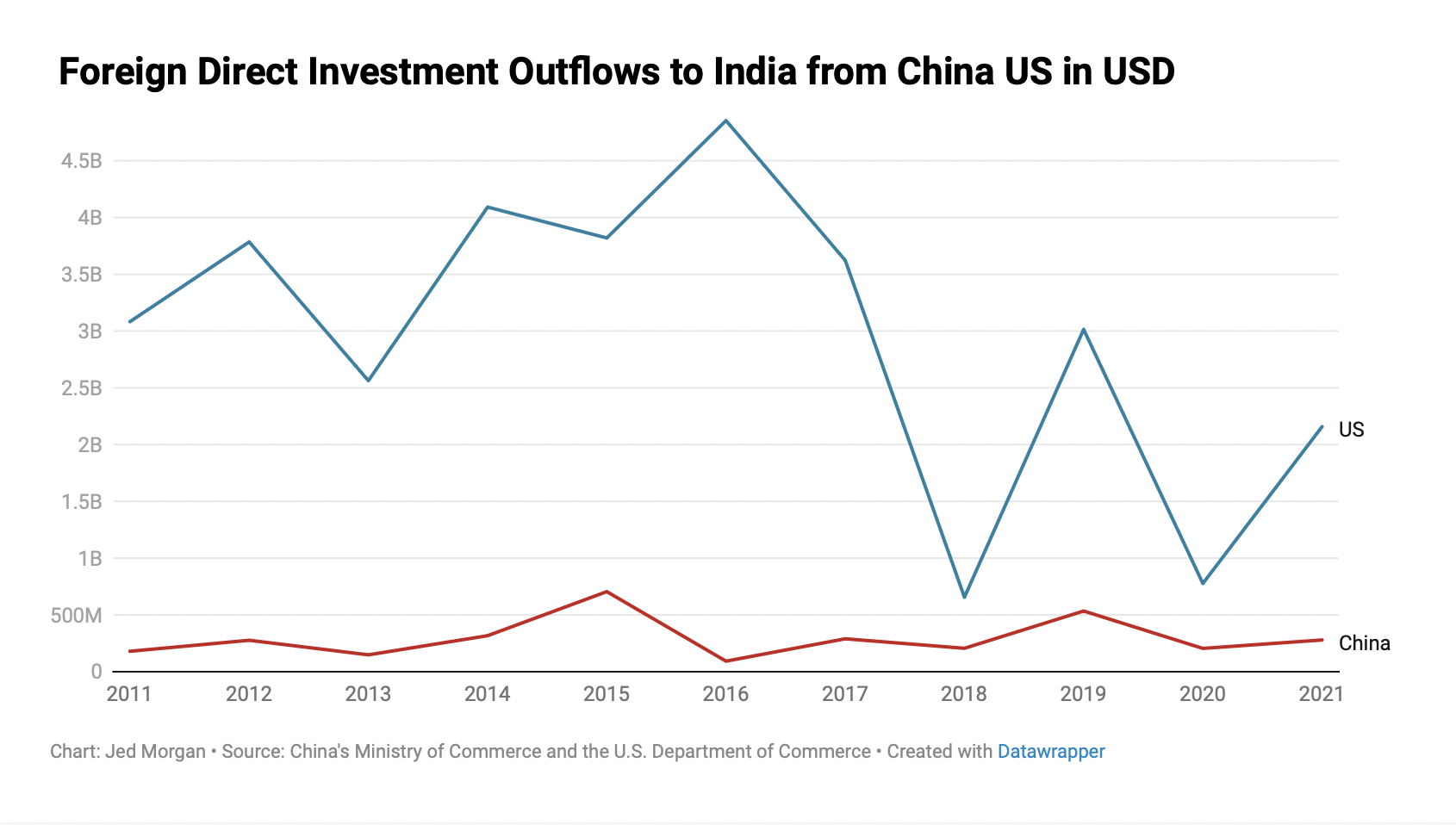

United States foreign direct investment—the quantity of foreign investment by residents of a particular country to external economies—into India is consistently greater than China’s. The large difference in FDI outflows from the United States and China shows either that United States residents or companies are more invested in the Indian economy than their Chinese counterparts, or that United States residents or companies have larger investment portfolios in India. China’s outflows have slowly increased from $180 million in 2011 to $279 million in 2011, while the United States has maintained investments totaling $2 billion despite a decrease in outflows after 2016.

Part of this dramatic decrease in FDI outflows from the United States to India is due to economic protectionism under former President Trump. In 2018, Trump imposed large tariffs on steel and aluminum, which disrupted many multinational steel companies that have ties to India. Trump also removed India from its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) status, removing its tariff-free exemption on exports to the US. It is unclear whether this trend will continue into the current decade, but high inflation rates and fears of a recession have probably kept FDI outflows low.

While the United States in some aspects has dominated the economic competition with China, China has rapidly developed its position as a necessary force in the Indian economy. This competition will only intensify as both superpowers continue to trade and enact new partnerships with the regional power. Looking towards the future, this November could have big implications for the United States-India economic relationship. A Trump victory could come with a retrenchment of economic protectionism and further stagnate United States FDI outflows to India. A second Biden term might facilitate further economic relations between the United States and India through the continued removal of tariffs.

Methodology:

I collected import/export data from India’s Ministry of Commerce and foreign direct investment outflow data from China’s Ministry of Commerce and the United States Department of Commerce. I collected trade data from 2005 to 2023, and FDI outflow data from 2011 to 2021. The data can be found here.