It wouldn’t be surprising if, five years from now, Brown still looks back at 2013 as the year of the Ray Kelly Event. It’s rare for a single moment to affect an entire community, especially ours — spread out as we are across disciplines, nationalities, outlooks and College Hill itself — but this was one of them. Protesters, engaging in what they would have called “constructive irreverence” (a term brought to our campus by President Paxson herself) sparked an intense debate on the nature of free speech and on the University’s long legacy of student activism. The discussion soon expanded beyond Brown’s campus, as news outlets ranging from Huffington Post to Fox News commented on the events of October 29.

Months later, the dust has mostly settled and the heated emotions of those tense days have cooled. The dialogue goes on, though, and the results of an investigation into the protests by a university-appointed committee have yet to be announced. Many questions still remain, and now one of the most central can finally be answered: Had the speech gone on as originally planned, what would Ray Kelly have said?

This article is not another opinion on what happened on October 29, but rather an attempt to analyze and critique the arguments Kelly would have raised had he been permitted to speak. The most immediate (and least exciting) insight from the speech vindicates one of the protesters’ main points: Kelly’s speech reveals no information the commissioner hasn’t shared before. If anything, the defensive tone and predictability of his argument shines a light on the intellectual vacuity of many of NYPD’s so-called proactive policing policies.

For starters, even the idea of “proactive policing” isn’t very consistent throughout Kelly’s speech. The commissioner would have started his presentation by giving an example of what this policy is meant to achieve: helping disadvantaged heads-of-household and community parishes keep their young people safe, educated and out of trouble. His story about Grandmother’s Love Over Violence and the NYPD-Brooklyn Clergy Coalition is indeed a great example of what proactive policing should look like, as it emphasizes peaceful interaction between police officers and civilian organizations based on reciprocity and mutual respect. These sorts of initiatives can and should provide underprivileged communities with much-needed tools of self-empowerment.The problem with this example is that it hardly has anything to do with the rest of the commissioner’s speech — or the reality faced by thousands of civilians every day on the streets of New York. His later comments on proactive policing leave aside any talk of communities, especially minority ones, in favor of a polemical focus on trying to validate NYPD’s more controversial policies. In this context, the introductory story comes off as little more than a vain attempt to gather sympathy before diving into more divisive topics.

Mainly concerned with legitimizing the ramped-up NYPD operations of the last 12 years, Kelly wastes no time getting to the big statistics. He boasts of the 72% overall crime reduction rate over the last two decades. Homicide figures come next, as Kelly cites a decrease of more than 80% since 1990. Shooting incidents also went down by 74% since 1993; by his calculations, NYPD policies implemented since 2002 have saved 9,172 lives.

At first glance, this appears to be the story of one of the most successful law enforcement initiatives in recent history. However, these achievements are not demonstrably the result of better policing.

By the mid 1990’s, New York City was experiencing a major drop in crime rates. The NYPD at that time was under the leadership of Kelly’s predecessor, William Bratton, who also defended the use of stop-and-frisk and proactive policing as crime-prevention tools. Every bit the policy hardliner as Kelly, Bratton also developed the computerized crime-tracking program CompStat, and implemented the “broken windows approach,” which proposes that more stringent enforcement of lower-level crimes can have a deterrent effect on more serious ones. These developments laid much of the groundwork for Kelly’s post-9/11 enhanced law enforcement policies. But in fact, crime was already dropping in New York since before many proactive policing policies such as stop-and-frisk were expanded under Bratton, and later Kelly. The statistics presented in the speech don’t necessarily indicate that the NYPD has become more successful or even more efficient.

The graphs Kelly included in his presentation show how crime rates — particularly homicides — have also gone down since 2002, the year he became Police Commissioner. 2012 ended with just 419 homicides in NYC — a 50-year low — and Kelly states that at the current rate, 2013 will end with about 330. However, this drop coincides with a massive reduction of street stops-and-frisks. The number of stops by police officers decreased dramatically from an all-time high of 200,000 in the first quarter of 2012 to around 21,000 in the third quarter of 2013. In the words of the New York Times editorial board: “If stops alone were holding back a hidden tsunami of crime, the city would have been overwhelmed by now.”

Like much of the discourse in the stop-and-frisk debate, Kelly needs to be reminded that correlation is not causality. A study by sociologist and NYU professor David Greenberg analyzed Bratton’s policies and concluded that they didn’t necessarily lead to lower crime rates. According to Greenberg, a host of other factors could have all played a part in making New York safer, including a growing economy, job creation, minimum wage raises, fluctuations in the illegal drug market, and decreasing crime rates at the national level. Some theories even speculate that an increase in family planning methods could be linked to the drop in crime. Although, as Kelly observes, crime dropped faster in New York City than in other cities, there remains no conclusive proof that revamped law enforcement is the primary cause of the trends.

Kelly goes on to mention two of the operations at the heart of his proactive policing agenda: Operation Impact and Operation Crew Cut, which he points to as sources of the improvements in New York’s crime rates without addressing any of the factors mentioned above.

The first of these policies, Operation Impact, is based on “hot spot policing,” which consists of assigning newly minted cops, fresh out of the academy, to areas with a high incidence of dangerous crimes — areas Kelly calls “designated impact zones.” This sort of crime mapping is, of course, unavoidable for good policing work. Some areas are simply more crime-ridden than others. But Operation Impact’s focus on recruiting new officers has its drawbacks. Because the program places rookies in high-crime areas, mostly populated by minorities, those with little experience may confuse these geographic correlations between race and crime for causation. The misapprehension only reinforces the stereotype of minority communities as naturally more crime-stricken, and could subsequently increase the tendency towards racial profiling by police. Race influences more than just which communities are targeted, or who is profiled and stopped; a recent report by the Office of the Attorney General of New York shows that minorities who are stopped-and-frisked by police are more likely to be arrested and convicted for misdemeanors and non-violent crimes than white citizens. This can both artificially inflate crime rates in disadvantaged communities and lead to insufficient policing in whiter areas of the city.

Another of Kelly’s initiatives, Operation Crew Cut, is based on the premise that gangs, or “crews,” are the perpetrators of a high percentage of violent crimes and should be monitored more aggressively. Part of the operation, according to Kelly’s text, involves identifying gang members who may just be “wannabes” and can still be guided down the right track. In providing resources for families to help their children stay away from illicit activity, this initiative appears closer to the vision of community-engagement projects that Kelly begins his speech with. However, the creation of a “team of investigators dedicated to monitoring social media” to catch any suspicious gang activity seems to justify the worries about invasions of privacy and misinterpretation of messages. Police officers take on false identities online, often posing as young women in order to gain access to suspects’ accounts. The police look for photos, taunts, boasts, threats and gang-specific lexicon, but all of these things are easy to mistake. Idle fights, empty threats and even the wrong slang — or being invited to the wrong party — could cause mistaken arrests. Says Kelly: “Gang members have posted photographs of themselves in front of a rival’s apartment building and surveillance pictures of those who they threaten to kill next.” But who hasn’t posted a picture of themselves in front of a building? Even if mistaken arrests don’t result in conviction, an open arrest can take time and effort to dismiss, and in the meantime can have high costs — financial and otherwise — for the suspect. When violence does occur, the stakes are much higher because the surveillance information allows police to build conspiracy cases.

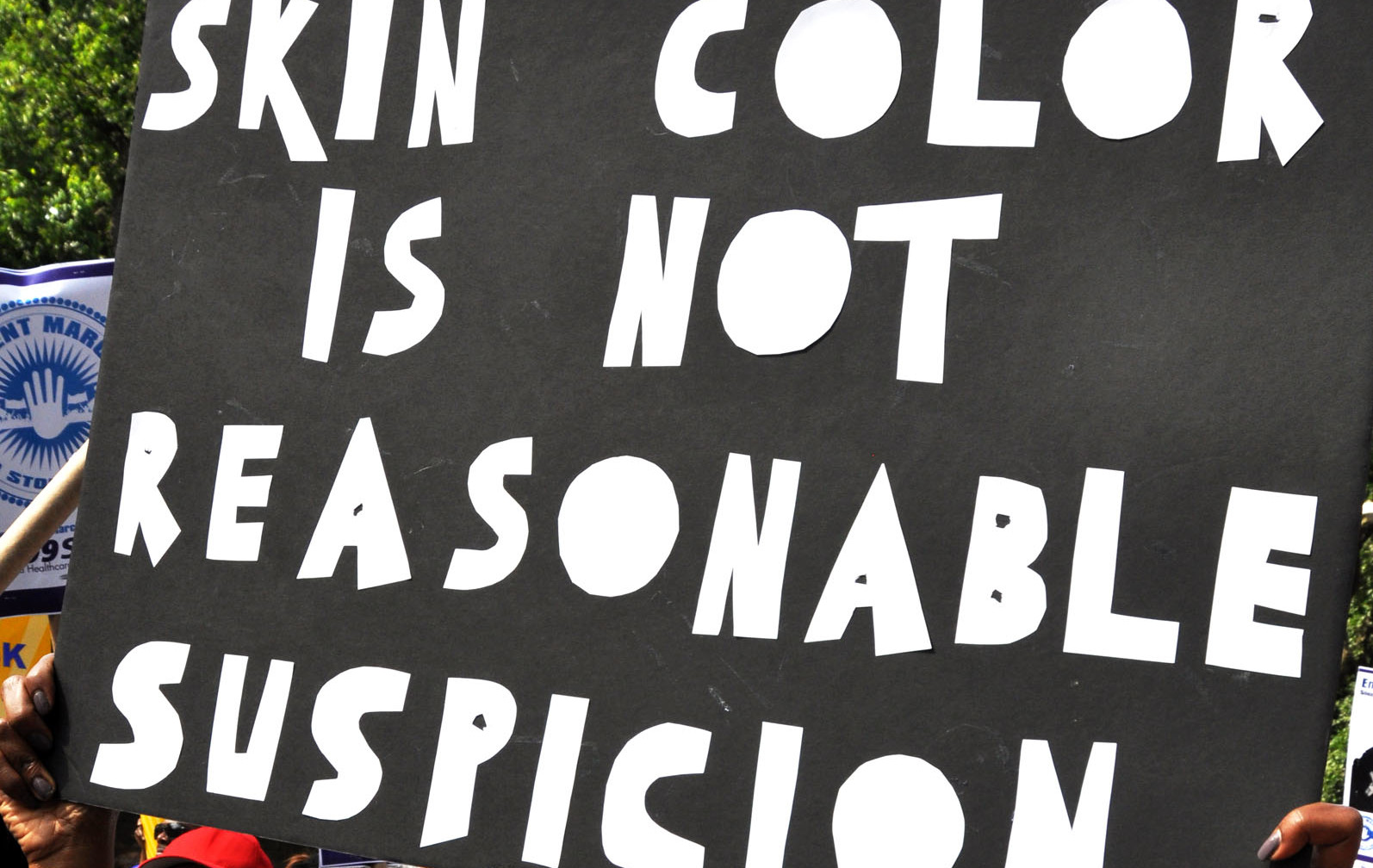

Finally, more than halfway through the speech Kelly brings up the topic of the hour: the NYPD’s so-called policy of “engagement,” otherwise known as stop-and-frisk. He describes the program as an extension of the “long-established right of the police to stop and question individuals about whom we have reasonable suspicion” and calls the practice “as old as policing itself.” It begs an interpretation of what exactly suffices as “reasonable suspicion,” especially given the high correlation between race and the stops.

Kelly begins his defense of stop-and-frisk with one of the most publicly celebrated outcomes of the policy: the seizure of more than 7,000 illegal weapons in 2012. But let’s put this into perspective. According to an Attorney General’s report, only 6% of all stops between 2009 and 2012 resulted in an arrest. Only 2% of these arrests (0.1% of stops) were due to weapons possession. Likewise, crimes involving violence represented only 2% of all stop-and-frisk arrests. The 7,000 weapons seized in 2012 were the result of 533,042 stops that year. That’s one weapon found for every 76 people stopped-and-frisked.

Despite the low percentage of stops that produce arrests, let alone confiscated weapons, Kelly praises them as a life-saving strategy that has primarily benefitted the city’s black and Latino communities. He says in his speech that groups made up 87% of all murder victims and 96% of all shooting victims in 2012, so the logic follows that confiscated weapons — especially guns — statistically contribute more to these groups’ safety than that of white communities.

Of course, Kelly doesn’t pay as much attention to the fact that blacks and Latinos are also stopped-and-frisked more often as well, complicating Kelly’s perception of what it means to be safer. In 2012, African-Americans, who make up 23% of the city’s population, made up 55% of all stops. Latinos, who comprise 27.5% of the city population, were involved in 32% of stops. On the other hand, only 10% of stops in 2012 involved a white suspect. The Attorney General’s report argues that stops of blacks and Latinos are not only “the majority of stops each year, but also the majority of the increase of stops.” Every year that stop-and-frisk keeps operating as it is, the racial disparity between whites and minorities increases.

The case of marijuana arrests resulting from the stops illustrates another key flaw in Kelly’s reasoning. Whites stopped and arrested for marijuana possession are nearly 50% more likely to have their case dismissed and to avoid conviction than blacks and Latinos. Ironically, considering Commissioner Kelly’s comments about making the city safer for minorities, the most common reason for stop-and-frisk arrests isn’t illegal weapons but marijuana possession. This preferential treatment feeds back into the NYPD’s institutional bias. Conviction statistics for marijuana possession are artificially skewed towards minorities and consequently help justify further racial disparity in stops.

These racial disparities were the main reasons Judge Shira Scheindlin declared the current stop-and-frisk policy unconstitutional under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments in the federal class action lawsuit Floyd v. City of New York. In his speech, Kelly says he “disagree[s] strongly” with the ruling and responds to Scheindlin by arguing that minorities are more likely to commit a crime, and therefore more likely to be stopped than white people, much in the same way that men are more likely to be criminals than women. Kelly also argues that “the racial distribution of stops generally reflected the racial distribution of arrestees.” That’s called a tautology: If individuals stopped are also those who get disproportionately arrested, of course that argument is then narrowly true. He also cites a 2007 study by the Rand Corporation indicating that the racial distribution of stops generally reflects the racial distribution of crime suspect descriptions. However, the Attorney General’s report shows police data indicating that only about 15% of stops are made on the basis that an individual fits the description of a crime suspect. Despite the circuitous reasoning and grasping analogies, Kelly’s argument still comes down to this: because crime suspects are more likely to be black and Latino, it is apparently justifiable to disproportionately stop people of these groups, even though the great majority of them will not match a crime suspect description. Simply stopping individuals who do fit a crime suspect description would seem to be a preferable solution.Kelly’s goes on to emphasize that Judge Scheindlin found only 6% of the stops between 2004 and 2012 to be “apparently unjustified.” Even if her judgment was sound, Kelly argues, there is no way that such a small percentage “shows a systematic practice of racialized profiling” or provides evidence of institutionalized racism. It makes one wonder about what Kelly considers a “justified” stop. After all, only 6% of stops lead to arrests. Furthermore, the Attorney General’s report indicates that the percentage of convictions resulting from those stops is half that of the arrests, or 3% of all stops. If the arrest and conviction rates are so low, how can this policy be justified against the other 94% of stop-and-frisk incidents at issue in Floyd?

The answer may just lie in the hands of the officers doing the stopping. According to New York’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, investigations of stop-and-frisk complaints revealed that some officers underreported their stops. In 2012, roughly a fifth of investigated complaints involved cases in which the officer in question had neglected to fill out a UF-250 form, required after every stop. An astonishing 33% of investigations dealt with officers who had not prepared a memo summarizing the details of the stop, also a vital part of the NYPD’s documentation process. Without this information — all of which is written out by the police officer conducting the stop — it is extremely difficult to prove that the stops were unconstitutional. Despite these findings, Commissioner Kelly states in his speech that NYPD has “become more careful about recording each [stop] in detail as required by law,” without elaboration.

Tellingly, one of the immediate reforms mandated in Judge Scheindlin’s ruling is meant to fix exactly this problem. Scheindlin proposed “revision of documentation” of stop-and frisk encounters, as well as a new UF-250 form that will include a detailed explanation as to why a search was performed. Another potential change might include a tear-off form stating the reason for the stop and explaining how to file a complaint, to be handed to the subject of the search afterwards.

Commissioner Kelly does not believe these measures are necessary. He cites a 1968 court decision, Terry v. Ohio, which upheld the use of stops by police departments. To use the commissioner’s phrasing, stops are “one of the tools of the job.” Limiting the efficiency of this tool would, in his opinion, have a negative impact on police officers’ work. But a closer reading of the Terry decision would show Commissioner Kelly that stops must be based on a “reasonable articulable suspicion” that a crime may occur. According to the Center for Constitutional Rights, an officer must be able to “articulate specific facts that give him or her a basis to reasonably suspect that criminal activity may be afoot.” These suspicions are meant to be specific to the individual being stopped, in order to avoid systematic, unjustified searches that could potentially infringe on civil rights. Judge Scheindlin’s ruling does not eliminate stops from the NYPD’s toolbox, but rather establishes accountable measures to ensure that the legal requirements established in Terry v. Ohio are actually followed.

But the NYPD’s active disregard for the “reasonable articulable suspicion” clause also affects NYPD’s counterterrorism and intelligence operations. As Kelly states in his speech, the department follows a set of rules called the Handschu guidelines to avoid violating the civil liberties of the individuals it investigates. The Handschu guidelines are the result of a 1985 case settlement between the NYPD and a group of leftists that sued for being spied upon for political purposes. Originally, the guidelines stipulated that detectives had to have “specific information” about a future crime to justify starting an investigation. Under the guidelines, no person can be subject to investigation because of their “political, religious, sexual or economic preference[s].” Like so many other guidelines, Handschu’s real message went out the window after the events of September 11. In 2003, a judge changed the Handschu rules to allow the NYPD intelligence chief to authorize investigations — both on book and undercover — with just a “reasonable indication” that a future crime was afoot. Kelly notes that the guidelines provide members of the police force the ability to attend public events, prepare reports of potential threats and view public online activities. But the public nature of much of the actions of the NYPD have been at best questionable, although Kelly promises that all operations are “in keeping with Handschu protocol.” The countervailing evidence is considerable: Operation Crew Cut and the attempt to befriend potential suspects online using fake personas, police attendance at “private event[s] organized by a student group,” and “undercover officers and confidential informants” entering mosques are just a few example of how NYPD’s intelligence operations have been increasingly relying on less than transparent methods.

Despite Kelly’s assurance that the department does not target Muslims or political dissidents, substantial complaints make a case for the contrary. From 2010 to 2012, the Associated Press published a Pulitzer Prize-winning series of articles on the NYPD’s secret monitoring of political dissidents and Muslim communities. One of the pieces tells the story of how the department’s intelligence unit went undercover to infiltrate the meetings of “liberal political organizations” in 2008 and kept files on activists and protesters from around the US — despite all of the monitored activities being completely legal.

Several of the AP articles highlight NYPD’s intrusion into the lives of Muslims both within and outside New York. Mosques were monitored and infiltrated, Muslim-owned businesses were cataloged, and any Muslims in New York that had legally changed their name to an Americanized one were automatically investigated. But perhaps most importantly, the AP reports argue that the counterterrorism program has not been as effective as it’s often said to be. Despite its mixed results, Kelly writes about the program as the crowning achievement of his time in office. Citing 16 plots foiled since 9/11, the commissioner makes a strong case for the unit’s efficiency. The AP reports also cite a list of 14 alleged terrorist plots that Congressman Peter King (R-NY) believes were stopped thanks to the NYPD’s counterterrorism efforts under Commissioner Kelly. However, the articles state that the list “includes plans that may never have existed, as well as plots that the NYPD had little or no hand disrupting.” All of this leads to doubts about the purpose and efficiency of Kelly’s prized antiterrorism unit.Beyond all of the quantitative data that’s left unaddressed, Kelly’s arguments completely ignore the physical, emotional and economic consequences that result from the NYPD’s flawed policies. African-Americans, Latinos, Muslims, and other discriminated groups are not receiving the essential social service of security from their state. Instead, they are constantly reminded of how intensely New York sees them as a threat. The alienating effects of this structural violence erode trust in state institutions and, ultimately, the rule of law. Kelly points out that a majority of NYPD officers are themselves minorities, apparently implying that somehow having a racially varied police force delegitimizes charges of racism. This point is one of the weakest in his speech, as it completely disregards the systematic, structural oppression that disadvantaged minorities face from many institutions of power — regardless of the races of their members. To put it bluntly, it doesn’t matter what background police officers come from if they’re required to follow a flawed protocol in order to do their job.

Despite all the criticism directed at policies like stop-and-frisk, Kelly still believes he has public opinion on his side, noting that his approval rating is 63%. However, the Quinnipiac University survey he cites showing 70% approval for the NYPD and an 83% approval rating for counterterrorism programs also contains some facts he neglected to mention. The same survey shows that 66% of those polled expressed support for creating a position of an inspector general to independently monitor the Police Department — one of the remedies proposed in the Floyd v. City of New York decision. More importantly, the survey shows that 51% of voters disapprove of the stop-and-frisk policy, with much wider margins of disapproval among the black and Latino communities.

Kelly holds on to the hope that an appeal against the Floyd decision will pull through and annul all the procedural alterations Judge Scheindlin ordered for the NYPD. He and his supporters — such as outgoing mayor Michael Bloomberg — celebrated when the U.S. Court of Appeals halted Scheindlin’s decision while it considered the city’s appeal. Explaining the decision, the three-judge panel that removed Scheindlin from the case said that they did so because Scheindlin had compromised “the appearance of impartiality,” by allegedly guiding the case to her courtroom in violation of judicial code and granting interviews while a decision was still pending.

While the outgoing commissioner might think that these developments will safeguard his legacy, he will likely be disappointed. The recent landslide victory of Democrat mayoral candidate Bill de Blasio spells certain change for the NYPD and its proactive policing policies. On the campaign trail, de Blasio condemned the current policies as racial profiling and pledged to support Judge Scheindlin’s ruling, as well as a commitment to apply the measures stated in her opinion. The city’s appeal of her decision will almost certainly be dropped as soon as he takes office. Though Kelly’s speech highlights his supposed concern for the wellbeing and rights of minorities, those same people will likely be the ones celebrating the end of his regime. Proactive policing’s greatest advocate will spend the coming years watching much of his policing framework being undone. If the facts are any indication, New York will be better off for it. Grandma’s love might be better directed at the next NYPD commissioner.

Editor’s Note: BPR invites readers to share comments, opinions, experiences, letters and articles in response to our ongoing coverage of Commissioner Ray Kelly. Please send your response to comments@brownpoliticalreview.org, and place “Ray Kelly” in the subject line.