One morning last month, Rhode Islanders woke up to the news that the National Rifle Association had been charged with the second-largest campaign finance ethics violation in state history. In a settlement reached by the Rhode Island Board of Elections, the NRA admitted that it improperly funneled money from its national Political Action Committee (or “PAC”) to the Rhode Island-specific PAC, illegal under state law. The PAC was fined a historic $63,000.

What the stories didn’t reveal? That the NRA’s wrongdoing, the record fine, and the shuttering of the NRA’s Rhode Island PAC was the result of the initial hunch of one person: Brown University student Sam Bell.

Bell’s story is certainly noteworthy for its David-and-Goliath appeal; the plot notes sound like a chilled-out version of “A Civil Action.” It’s also remarkable for the NRA’s astonishingly poor cover-up (their reports defy simple arithmetic) and the even more stunning realization that nobody checked them for ten years. But the real reasons Bell matters — the success of his legal complaint and the clues that led him there — together represent something else entirely: a new model, potentially, for enforcing campaign finance laws in Rhode Island and around the country.

Bell is a Ph.D. candidate in Brown’s geology department — not exactly the campus war room, unless you apply a broad interpretation to “digging.” But it’s the 24-year-old grad student’s other job that supplies his political adrenaline, as State Coordinator of the Rhode Island Progressive Democrats. Tall and ebullient, with a perennial tie and glasses that accentuate a scrutinizing demeanor, Bell sharply resembles the consummate grad student, including a thin, brass voice almost perfectly designed for administering factual correction. His age and background, in a way, are camouflage for political foes that get too casual with the facts, whom Bell can skewer (and I can testify) with an encyclopedic knowledge of state politics and polling data down to the district level.

I visited Bell at one of his monthly statewide meetings. A dozen coat-clad adults, all over 40, sat in a fluorescent conference room and looked on while Bell comfortably wrapped up a PowerPoint on monetary policy. Later, Bell told me that his suspicions in the NRA case began not with fishy numbers or a secret source, but an old-fashioned political ass-whooping. So ass-whoopy, in fact, that something didn’t add up.

“We failed miserably at passing an assault weapons ban,” said Bell, referring to the measure’s failure last spring, and citing a failure to act from the legislative leadership despite their repeated official statements of support. That seemed odd to Bell: after all, constituent support statewide for gun control reliably clocks in at overwhelming levels. Sixty-four percent approve an assault weapons ban, including 86% of Democrats, while the NRA received a toxic 56% “unfavorable” rating, both according to polling data from last year. Bell noted that more Rhode Islanders support gun control than supported Barack Obama in the 2012 election.

Then Bell learned that the speaker of the house, the senate president and both chambers’ majority leaders all had accepted money from the NRA — a lot of money. An independent analysis of public campaign finance reports by BPR confirms that the NRA’s Rhode Island PAC spent over $162,000 on Rhode Island elections since 2002, and the speaker and senate president each took $2,700 and $5,700 in the same time frame, respectively. True, Bell reasoned, the Rhode Island legislature is notoriously conservative on issues of reproductive health and voter I.D. — a fact made even more frustrating by Rhode Island’s misnomer status as the most liberal state in America, but even that didn’t make much sense either, per the same polling data that Bell now knew by heart. The mystery wasn’t the legislature’s willingness to take the money, but the money itself. In other words, if the NRA was so unpopular, who was writing the checks?

“We wondered how this group was able to raise so much money,” said Bell. “We had never seen an NRA fundraiser, never heard about one.”

Then he consulted the public records in the Board of Elections archive (the same source of BPR’s analysis) where Bell noticed the organization hadn’t reported a single donor in ten years. Such a practice is only legal if a donation is less than $100, known as “aggregate individual contributions.” Additionally, Bell said that the NRA’s federally filed expenditures matched dollar-for-dollar those of the NRA’s Rhode Island-specific PAC — again, every year dating back to 2002.

Put another way: the NRA didn’t even attempt to hide what plainly appeared to be suspicious activity. Something was clearly up. And Bell was the first to have checked in over ten years.

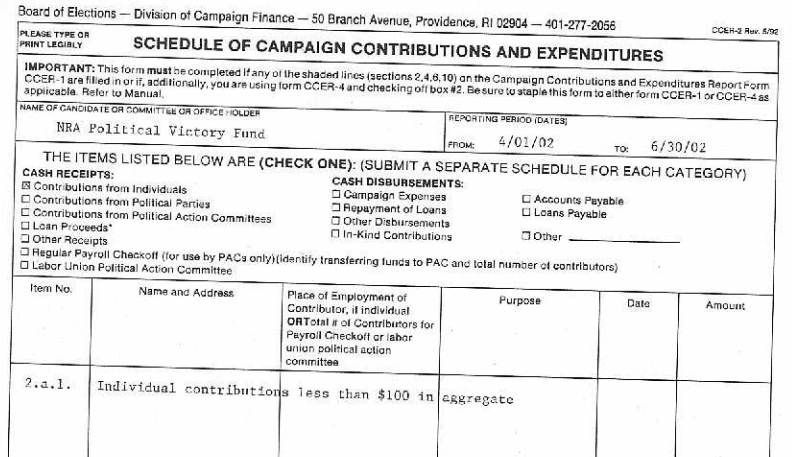

Here’s what Bell saw when he consulted the public records. First, he saw the same pattern repeating over and over again in the NRA Rhode Island PAC’s reports to the state Board of Elections: a large sum listed for “aggregate contributions,” and a long line of goose eggs for every other category:

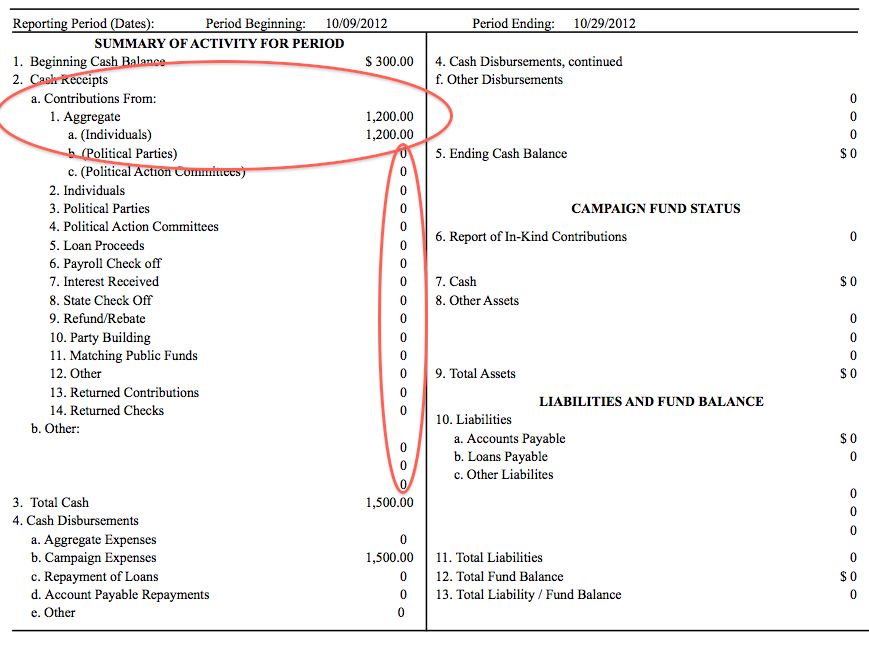

Those many “zeros” coincidentally line up with all the categories for which PACs don’t have to report their donors. The $1,200 in the example above was filed in the seven days before the 2012 election in October. Notice that the NRA quickly spends all of its “aggregate contributions” in the same reporting cycle, ending with a “Cash Balance” of zero. BPR’s analysis of records from the Board of Elections shows that of the 65 reports that the NRA filed with the Board in which they disclosed receiving contributions, 60 followed this identical pattern — listing all receipts as aggregate individual contributions, and spending the exact amount in the same period. The five exceptions in which the NRA reported their receipts were all cases of voided checks.

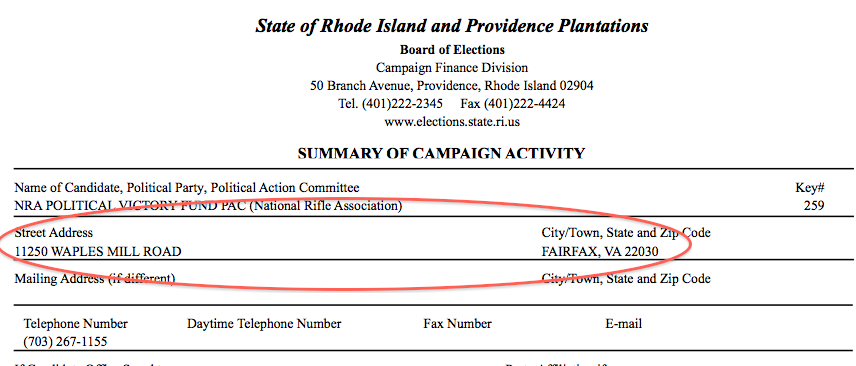

Next, Bell noticed that the addresses listed for the NRA’s national and Rhode Island PACs were identical, and both registered as the “NRA Political Victory Fund.” Below is an example from the NRA’s public reports with the Rhode Island Board of Elections:

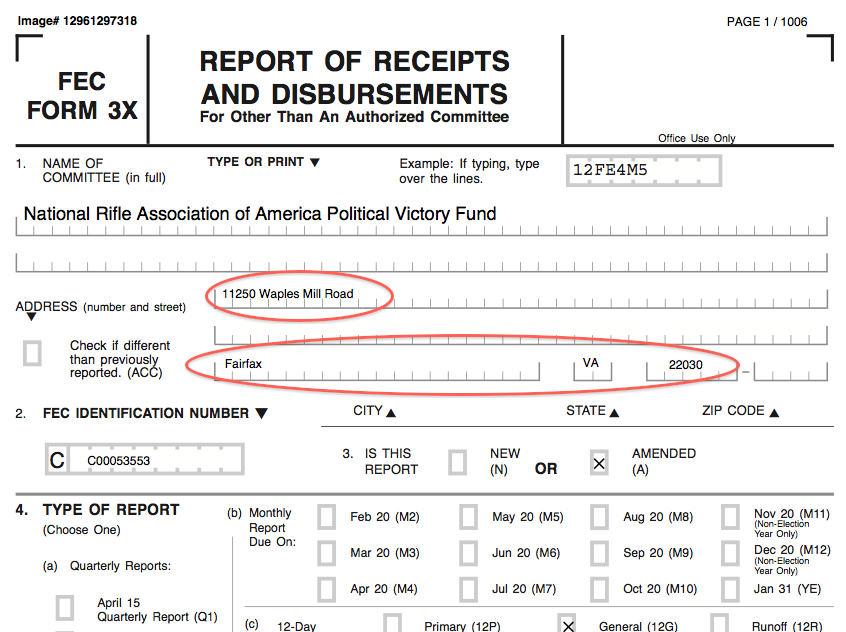

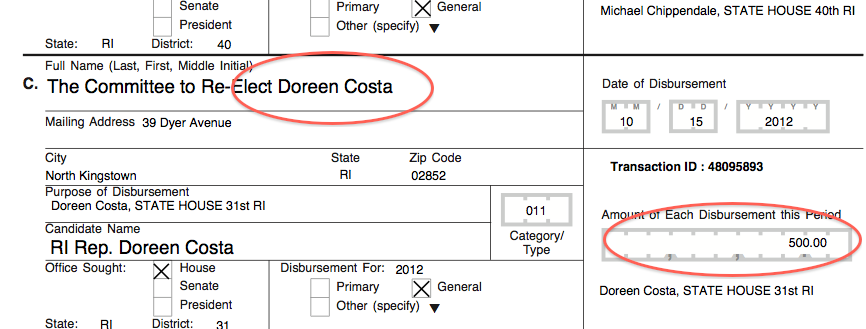

And here is the NRA’s filing in the same month with the FEC:

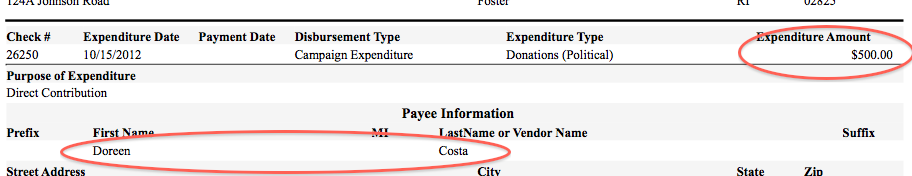

You can see they didn’t exactly try to hide it. Second, and related, the NRA double-listed their campaign contributions, or “disbursements,” in both reports. Here’s one example from the NRA’s Rhode Island PAC, in their October report to the state Board of Elections:

…and the exact same contribution reported in the same month to the FEC:

Again, about as inconspicuous as Justin Bieber at a DMV.

It raises a key question. Campaign finance is a notoriously dense field. The notion of keeping hopelessly opaque and unclear documents “transparent” before the public is often seen as a cruel joke. It takes lawyers to enforce campaign finance laws — and most of the time they get frustrated: see Harvard Law Professor Larry Lessig’s march across the New Hampshire tundra just to get a few people to pay attention to the issue at all. But the NRA-Bell scandal forces us to reduce this sad canard to its core. Does the NRA assume that people care so little — are they so contemptuous of the law and the intellect of those who might enforce it — that they don’t even pretend to comply?

Bell was about to find out. With the pro bono help of the law firm CFO Compliance, and with the crowd-sourcing teamwork of his Progressive Democrats posse, Bell began building a case.

In September of last year, Bell filed a formal complaint on behalf of the Progressive Democrats, alleging three specific violations. Here is the Campaign Finance 101 digest of what Bell alleged:

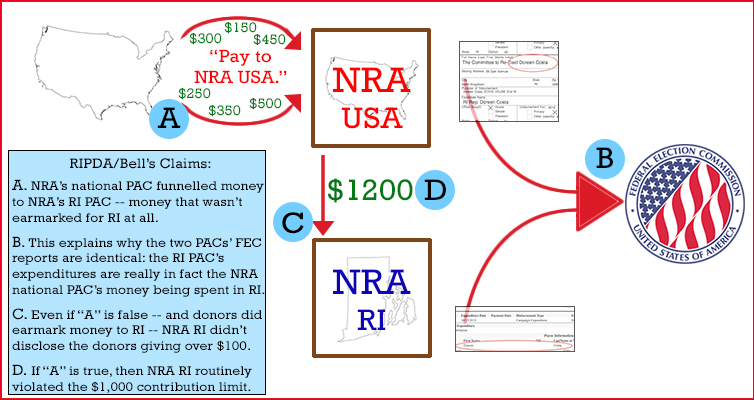

1. A federal-state PAC conspiracy. Rhode Island law says that if a PAC is registered in Rhode Island, it cannot receive money from any federally registered PAC. The first and most obvious complaint alleged that the NRA’s federal PAC was sending money to the Rhode Island state PAC — a violation of Rhode Island law.

2. A failure to report donations. Rhode Island law says that any candidate, campaign or PAC must disclose the name and address of anyone who donates more than $100. The second complaint alleged that there was a high likelihood that many “donors” to the NRA’s Rhode Island PAC (if there were any at all) must have given more than $100, just by sheer odds. According to BPR’s analysis, the NRA Rhode Island PAC’s “aggregated individual” (i.e. undisclosed) contributions amounted to over $160,000. For the NRA to be innocent, that means that not a single donation — once, ever — over a ten-year period and among these hundreds of thousands was ever over $100.

3. A violation of the overall campaign contribution limit. Rhode Island Law limits any candidate, campaign or PAC from receiving more than $1,000. If Bell’s first complaint was true, that would likely mean that the NRA was sloshing it’s money from its national coffers into the RI PAC. Since many of these donations were over $1,000 (in the October 2012 filing above, the contribution is $1,200) — and if that money came from NRA’s national PAC as Bell alleges — that would mean the NRA’s Rhode Island PAC illegally received more than $1,000 from a single source.

Bell’s Progressive Democrats filed the complaint in September, and after that… well, we don’t really know what happened after that. The Board of Elections conducts its investigations under strict confidentiality.

Here’s what we do know. On October 3, the NRA’s Rhode Island PAC formally dissolved. Whether this was part of the negotiations, or a political attempt to save face, no one knows except for the NRA. It seems clear that without the Progressive Democrats’ complaint, the state of Rhode Island would be one NRA Political Action Committee richer.

Then, on January 17, the Board of Elections announced their closed-door settlement with the NRA, fining the organization a historic $63,000. Again, how that number was reached is confidential. But far more intriguing was the rationale used by the Board of Elections. The Board found the NRA guilty of funneling money from its national PAC to its Rhode Island PAC — point #1 in Bell’s three-part complaint. For that, the NRA faced an enormous fine. But the Board found the NRA not in violation of Bell’s complaint #2 and complaint #3: that is, NRA RI was not fined for accepting donations over $100 without disclosure, nor for accepting donations over $1,000.

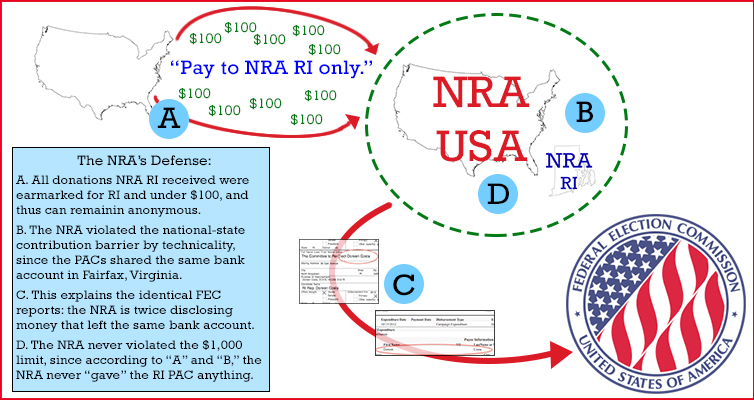

What defense did the NRA use to bring the Board to their side on these latter two points? The NRA argued that its Rhode Island PAC was maintained and operated “within” the NRA national PAC’s finances. In other words, they shared the same bank account.

Think about that for a second.

The spirit of the law — the idea of precluding national PACs from giving money to state PACs — is meant to create separation between national and state money, and to keep state organizations free of outside influence. In response to the allegation that it violated a law meant to keep national and state PACs separate, the NRA argued that the only reason its national and state PACs looked so similar was “only” because the two PACs shared an address, legal liaison and bank account — such that they became indistinguishable from one another. That was their defense.

Yet as counterintuitive as their defense may seem, it offers the brilliant catch-22 of exonerating itself from Bell’s second and third complaints. If the sharing of bank accounts is an acceptable legal explanation, then suddenly there would be no realistic way to know if the NRA’s “Rhode Island PAC” (indistinguishable from the national PAC for financial purposes) ever inappropriately accepted donations of more than $100 or $1,000. Remember, the NRA isn’t required to say if checks or cash were earmarked especially for the Rhode Island PAC. If NRA national and NRA Rhode Island indeed shared the same bank account, we can only take the NRA’s word that every dollar of “aggregate expenditures” was really intended for Rhode Island, and not just sloshed into Rhode Island as needed from the national PAC’s war chest. Why is this, you ask? Because, that’s why. Welcome to the Kafka novel that is American campaign finance.

If you’re confused as hell, that only means you’re paying attention — campaign finance is confusing. To the left are Bell’s claims and the NRA’s defense spelled out graphically. Click on each below for an expanded view.

Notice how conveniently self-referential the NRA’s defense appears — almost too perfectly, it fits the explanation one would expect if we were to cover up the funneling of anonymous national cash into state politics, hand-in-glove. In that scenario, it would appear that the NRA admitted to a lesser offense in order to deny the far more egregious ones, especially the $1,000 limit.

Notice how conveniently self-referential the NRA’s defense appears — almost too perfectly, it fits the explanation one would expect if we were to cover up the funneling of anonymous national cash into state politics, hand-in-glove. In that scenario, it would appear that the NRA admitted to a lesser offense in order to deny the far more egregious ones, especially the $1,000 limit.

“This is why the NRA had to argue they were running the RI PAC inside their national PAC bank account,” Bell said in an email. “If they admitted that they transferred money from the national PAC to the state PAC, nearly all of those contributions would be in violation of the $1000 rule.” The DiCaprio-themed bank-account-within-a-bank-account alibi seems exactly big enough for a $1,000 limit violation to fit into.

All told, the NRA’s alibi might go down in history as a contender for the award given for Most Chutzpah Ever Summoned in a Legal Defense. Meanwhile, Bell says there are still major questions in the case, including strong, emerging evidence that the NRA’s claims are spurious or at least highly doubtful.

“We’re still looking into this,” Bell told me. “We’re still trying to collect data, still trying to figure out exactly what happened. I don’t think that this thing is fully over.”

Next week, BPR will take a close look at Bell’s claims, evaluate the defense that the NRA has offered, and talk to campaign finance experts about how Bell’s example might be followed in other states.