On September 2, in a village outside Chișinău, Moldova, a young woman, known to her associates as Ana Nastas, handed out a stack of anti-EU leaflets rife with misinformation that had been produced by Ilan Shor, a Russophilic Moldovan oligarch and politician. Just six days earlier, Ana had 15,000 Russian rubles (a little over $150) funneled into a Russian bank account recently opened in her name, using only a photograph of a forged identification card. She was one of many Moldovan citizens regularly paid to attend protests and spread pro-Russian electoral propaganda—and one of the 130,000 bribed for their votes. But her name wasn’t really Ana Nastas, and she wasn’t interested in supporting Shor’s political efforts: She was an undercover journalist infiltrating the ranks of his organization.

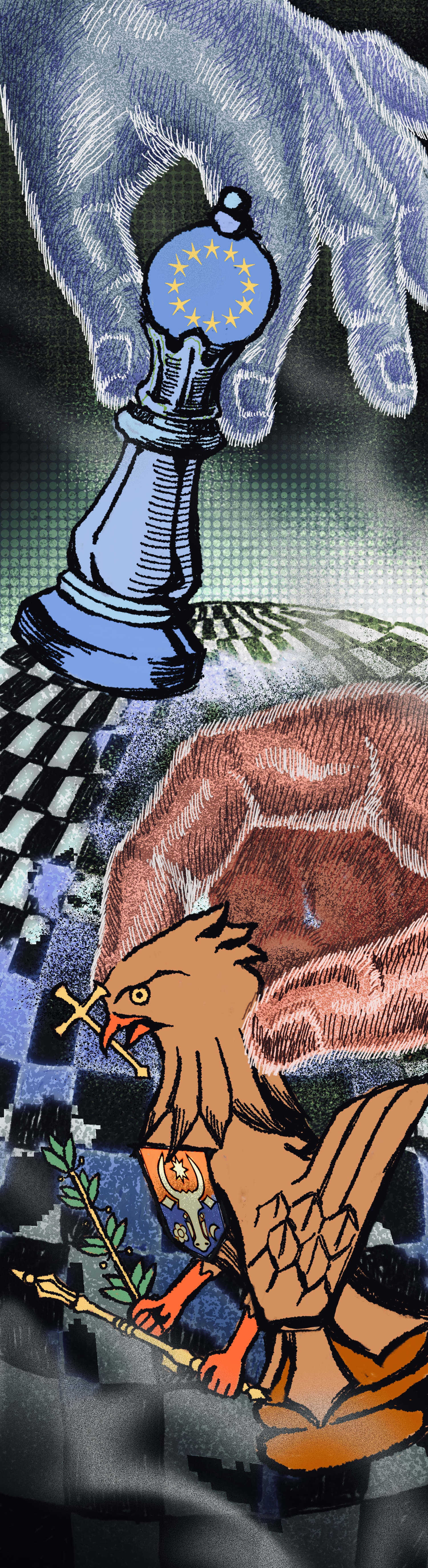

This covert operation, sponsored by the independent newspaper Ziarul de Garda, revealed propaganda distribution, vote-buying, and electoral interference by Russian-backed politicians in Moldova on an unprecedented scale. Its purpose? To sway the October 20 referendum that would decide whether Moldova embarks on a path to EU accession or abandons its European dreams in favor of Russia.

The pivotal October referendum asked citizens whether they supported amending the constitution to enshrine the country’s goal of acceding to the European Union. The results were strikingly close and contested—50.46 percent of voters endorsed the constitutional amendment, while 49.54 percent opposed it. The victory of the “Yes” vote does signal a meaningful commitment to a pro-European trajectory and the goal of EU accession by 2030, but the significant domestic opposition to the referendum implies future resistance to Europeanization. The European Union therefore has a limited-time opportunity to harness the momentum created by the referendum to legitimize Moldova’s European ambitions—even if doing so necessitates concessions on the economic and political structures required for accession. With Russia already invading Ukraine and scuttling hopes of Georgia joining the European Union, it is only a matter of time until Moscow tips the scales back in its favor. The European Union cannot wait for a more economically stable or LGBTQ-friendly Moldova.

The history of Moldova-EU relations is complex, if short. Formal ties began with the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement in 1994, which laid the groundwork for economic collaboration and political dialogue. Two decades later, pro-European president Nicolae Timofti signed the EU-Moldova Association Agreement, which deepened economic links. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in March 2022, Moldova, along with Georgia and Ukraine, formally applied for EU membership in an effort to reorient itself to the West in the face of Russian aggression. Moldova was promptly granted candidate status, with accession conditional on instituting judicial reforms, anticorruption measures, and improved human rights protections. In response, the Moldovan government approved a National Action Plan for EU accession for 2024 to 2027, outlining specific measures to align with the EU acquis across 33 chapters. Accession negotiations opened in June 2024.

Even as Moldova has moved closer to the European Union in policy, its geopolitical and cultural identity has remained shaped by its precarious position between Europe and Russia. Today, the nation is largely divided between pro-European and pro-Russian orientations, often along ethnic and linguistic lines: Ethnic minorities, including Russians, Ukrainians, and the Gagauz, a Turkic-speaking Orthodox Christian group, tend to reject EU membership and support closer ties with Russia. This Russophilic stance is due not only to cultural affinities but also to Moldova’s economic dependence on Moscow.

This concern over economic dependence is not unfounded. Moldova’s economy is propped up by trade with Russia, which Moscow has historically weaponized. In 2006, it embargoed Moldovan produce after Moldova’s government rejected a federalization plan proposed by the Kremlin. Moldova also relies heavily on Russian energy, creating a substantial vulnerability for Russia to exploit. From 2022 to 2023, Russian state-owned Gazprom cut gas deliveries to Moldova by 30 percent—which, in tandem with a bombing campaign of Ukrainian electricity infrastructure, caused a period of electricity blackouts. Dependency on Russia as a trade partner has forestalled economic development and trapped Moldova in a coercive economic relationship. The only remedy is integration into European markets.

Beyond covertly propping up Russophilic parties and politicians, Russia’s economic and information wars in Moldova have a secondary aim of distancing the country’s values from those of the European Union. Opposition parties frequently weaponize widespread anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment to discredit pro-European President Maia Sandu, going as far as creating deepfakes of her speaking in support of the LGBTQ+ community. Anti-EU evangelism frequently features references to the EU’s “homosexual propaganda” and fearmongers about EU integration disrupting cultural and religious norms in Moldova. These disinformation campaigns impede progress toward human rights for LGBTQ+ people, which the European Union has mandated as a condition of accession. As such, Russia’s covert operations not only push Moldovans away from Western values but also simultaneously drive EU leaders away from Moldova. Moldova’s economic dependence, fear about Russian military presence in the breakaway Transnistria region, and inability to defend itself from a disinformation war waged by the Kremlin actively hamper efforts to develop in line with EU demands. Even still, a majority of Moldovans favor EU accession.

The eastward expansion of the European Union is an essential geopolitical move. For Moldova, joining the European Union represents a path toward security, economic growth, and alignment with Western values. EU membership offers a free flow of people, goods, and services across borders, includes smaller states in major geopolitical discussions, and grants access to powerful, stable Western allies. But crucially, for the European Union, supporting Moldova’s accession means fighting back against Russia’s growing influence, strengthening its eastern flank, potentially boosting the future reconstruction of Ukraine, and promoting democratic norms across the continent. Just as EU membership would liberate Moldova from economic dependence on Russia, it would distance the two countries diplomatically. There is historical precedent for accession weakening ties between Russia and candidate states even prior to EU entry. For instance, Bulgaria and Romania introduced visa requirements for Russia in the run-up to their 2007 accession.

The European Union has witnessed the destabilizing effects of Russian interference in states that express pro-Western ambitions. Of the three states that make up the Association Trio—Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia—only Moldova remains relatively unscathed by Moscow. For the latter two, it may be too late. Ukraine is in the throes of a brutal Russian invasion that will leave the country economically and socially devastated, and likely partially annexed. Georgia recently took a hard pro-Russian shift in a dubious election that saw a radically Russophilic party retain power, largely due to popular fears of future Russian aggression. The promise of eventual accession is simply not enough to reassure citizens and states that their futures lie with Europe, not Russia—and crucially, not enough to dissuade the Kremlin from interfering with, coercing, or actively invading candidate countries. We may never know whether more proactive cooperation with Ukraine and Georgia might have impeded or even prevented Russian efforts to pull these states deeper into its sphere of influence. LGBTQ+ rights and economic stability can come later—if the European Union wants to counteract the rapidly encroaching Russian domination of Eastern Europe, it must act now to prevent Moldova from suffering the fate of many of its neighbors.