Following the geopolitical turmoil wreaked by the coronavirus pandemic, leaders in the United States have become acutely aware of a glaring flaw in the neoliberal model of economic globalization that has dominated for much of recent memory: an overdependence on expansive, multinational supply chains. Granted, there is scant bipartisan consensus on exactly how to remedy this problem. Former President Biden signed legislation like the CHIPS and Science Act to gradually increase domestic manufacturing of semiconductors, while President Trump aims to jolt stagnating sectors into prosperity via steep tariffs. Though these agendas differ radically in their approach, they are grounded in a common concern over supply chain vulnerabilities.

This transition in the United States’ economic order will be contingent on the ability to acquire and refine critical mineral resources, which are vital to defense, energy, transportation, and other crucial industries. However, access to these resources—which include Rare Earth Elements (REEs), lithium, and other minerals—is determined by the geographic distribution of deposits, naturally making them susceptible to monopolization. The United States’ control over mineral resources in the coming decades will become an increasingly important factor in its market power and geopolitical leverage.

Despite efforts to strengthen America’s critical mineral capacities, progress has been slow in countering other nations’ long-standing dominance over select resources, particularly adversaries. China, for instance, currently controls around 70 percent of global REE mining and over 90 percent of refinement, significantly outpacing competitors. China’s emphasis on REEs is rooted deeply in its economic legacy—as Deng Xiaoping declared in 1987, “the Middle East has oil. China has rare earths.” China’s 44 million metric tons in reserves highlight the pressing need to bolster the United States’ meager 1.8 million metric tons of reserves. Despite earlier environmental production limitations on REEs, China has moved in recent years to remove such barriers and has increased quotas to maintain its strong position. The CCP has coupled this advantage with export limits, allowing it to wield tremendous power over industries like wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, and military systems. This dynamic has been on prominent display in 2025, as China uses rare earth exports as a bargaining chip in response to American tariffs, sending a wave of concern through US defense and automotive manufacturing executives.

The United States and its allies have undertaken several initiatives in recent years to erode Chinese REE dominance and the refinement bottleneck. The United States, Canada, Japan, Australia, and other partners jointly launched the Mineral Security Partnership in 2022, intended to coordinate investments in critical mineral supply chains. Still, it will be an uphill battle to overcome China’s advantages in cost efficiency and favorable regulatory environment.

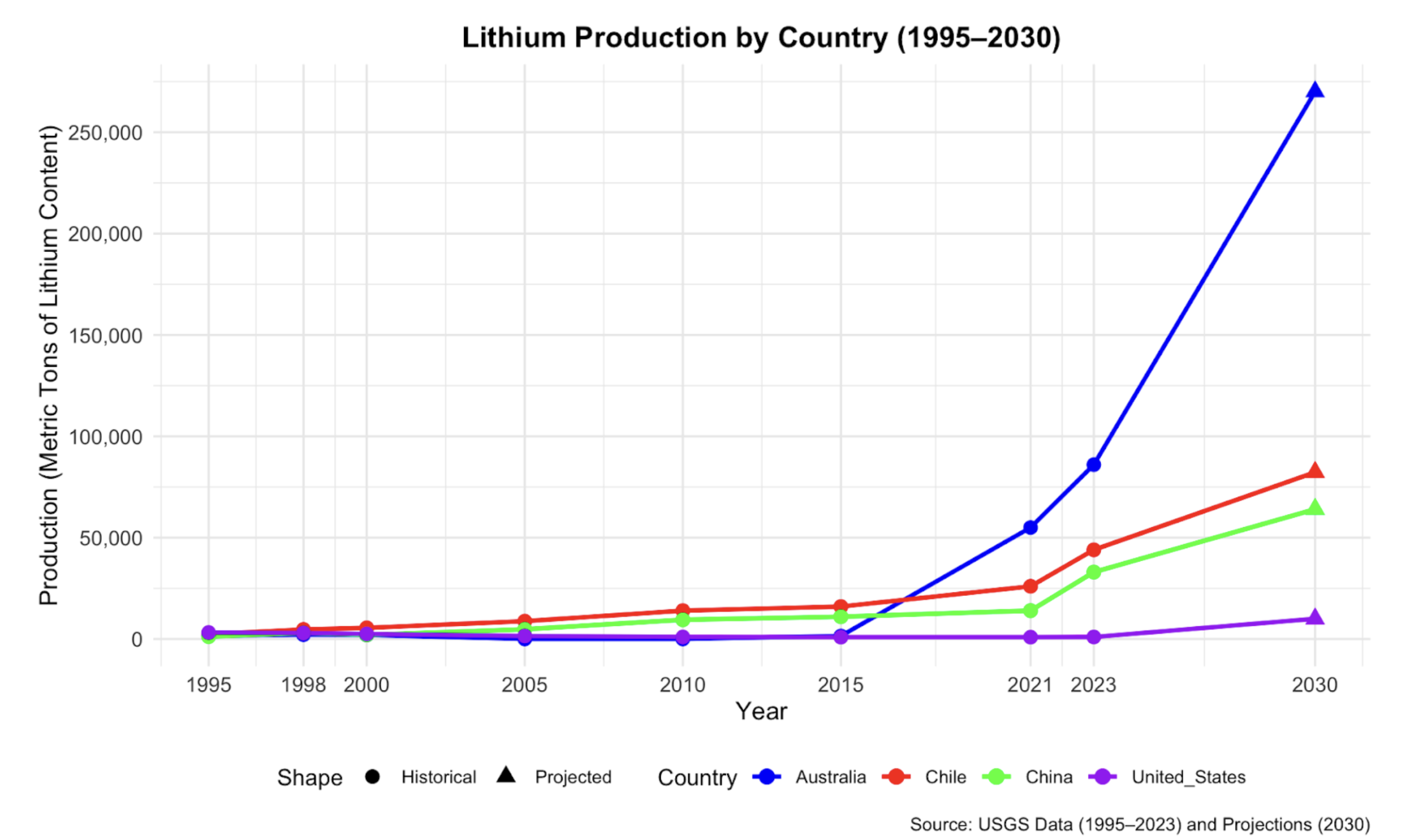

Aside from REEs, another mineral of concern for the United States is lithium, which was designated as “critical” in the Energy Act of 2020. Although the United States once led lithium production, this advantage quickly dissipated in the latter part of the 20th century. The World Economic Forum estimates that US domination over lithium production persisted until the 1990s, when it was swiftly usurped by foreign players. Production today is concentrated almost exclusively in China, Chile, and Australia, with China controlling around 70 percent of total lithium refining. As global demand continues to grow quickly, US control over lithium is poised to remain modest, despite recent investments in domestic production capacity.

In the coming years, the United States will need to strike a delicate balance between eliminating unnecessary supply chain vulnerabilities and forming strategic relationships to strengthen its critical resource capacities. At least in the short term, collaborative initiatives like the Mineral Resource Partnership can reduce the alarming gap between China and the West in production and refinement. The benefits of these multinational resource-sharing projects, however, will only go so far when trying to compete with the sheer scale of China’s operations, and deft policy maneuvering cannot indefinitely outrun geographic destiny. The United States needs to confront complex questions about how to radically overhaul its domestic extraction, production, and refining efforts.

Methodology

Using the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) formula, I analyzed mineral extraction data from select leading nations over certain periods to project long-term growth: R = (Pf/Pi)1/n-1, where R = CAGR, Pf = final production value, Pi = initial production value, and n = length of the period under consideration. Please note that these projections are based on available data that, relative to the history of human mineral extraction, represents a comparatively small sample. The landscape of global mineral extraction could change drastically in a short period (e.g., factors like investment, regulatory developments, new geographic discoveries, etc), rendering these projections inaccurate.

Repository – https://github.com/juice-alt/bprminerals/blob/main/lithium_viz