From an aerial perspective, the City of Providence is distinctively marked by a 20-acre strip of dirt and grass cutting through the city. Interstate 195 used to run across this now-empty path, dividing the city into an awkward horseshoe shape. In 2009, the state moved part of the highway to the city’s outskirts, freeing up the strip for development. The land has since been dubbed the ‘LINK’ land, after the hope that developing it will reunify previously separated parts of the city. However, current plans to develop the land fail to recognize the history of inequities in Providence that continue to separate the city to this day.

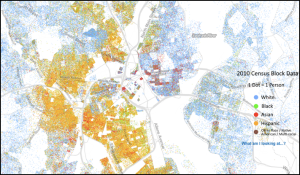

The national highway system was created in the 1950s, and during that period the routes for I-195 and I-95 – the two highways that cut through Providence – were chosen. Many communities within cities across the country did not want noisy, congested roadways running through their neighborhoods, and so, as is often the case, highway routes were often chosen to favor affluent white residents. In Providence, the paths of I-195 and I-95 followed suit, physically dividing the city and isolating already marginalized communities of color. To the west and south of the highway, the neighborhoods are predominantly low-income and Hispanic, and I-195 cut off these parts of the city from the downtown area and the we althier neighborhoods to the east. Thus through city development, Providence used transportation infrastructure to reinforce segregation, and these divisions still remain, preserved by the two strips of highway.

althier neighborhoods to the east. Thus through city development, Providence used transportation infrastructure to reinforce segregation, and these divisions still remain, preserved by the two strips of highway.

In addition to highway construction, discriminatory lending policies have upheld the city’s segregated neighborhoods. Dating back several decades, banks and sometimes the government have limited investment in non-white neighborhoods regardless of credibility ratings, through a process called redlining. The legacy of discriminatory housing policies is still apparent in Providence’s segregated neighborhoods and the low levels of home ownership among residents of color, as pointed out by a 2014 article in the Providence Journal. According to 2010-2014 American Community Survey data, only 24 percent of Hispanic residents and 32 percent of black residents in Providence own homes, compared to 44 percent of white residents. These discriminatory practices continue to this day; in 2014, Santander Bank reached a $1.3 million settlement in a lawsuit alleging that the bank, since 2009, had decreased lending in Providence’s minority neighborhoods while simultaneously expanding loans to white neighborhoods.

This history of discrimination and separation further exacerbates inequalities between Providence neighborhoods. A recent report from the Brookings Institute found that Providence has the fifth-largest income inequality gap among all US cities. People in the 95th percentile for income earn over 15 times more than those in the 20th percentile. Other studies found similar results: An analysis by Bloomberg News ranked Providence as the city with the 9th greatest income inequality in the country. This gap in wealth also has racial dimensions. According to American Community Survey data analyzed by the Providence Journal in 2013, white residents in the city had a median household income of $50,903, compared to $31,377 for black residents and $26,398 for Hispanic residents. Even worse, this disparity is growing. From 2010 to 2013, the median household income of white residents grew by 9.0 percent while that of black and Hispanic residents shrank by 3.1 percent and 10.7 percent, respectively.

After decades of discriminatory practices like redlining and physical separation through infrastructure, combatting inequities within Providence and other cities presents difficulties as they become heavily engrained within certain neighborhoods. However, developing the LINK land with the goal of bridging this divide seems like a good place to start. This sector occupies a unique social and geological position in the city as it abuts the wealthy eastside, the mostly low-income South Providence, and the central downtown. Additionally, most of the land is either undeveloped or vacant, so, in a sense, the land is an open canvas, capable of being shaped into whatever type of neighborhood developers push for.

One way to bring the many facets of the city together through this district is by encouraging the development of mixed-income housing, where developers reserve a certain ratio of apartments specifically for low-income and middle-income families within a residential complex. Designed correctly, mixed-income housing can improve living quality and safety for low-income residents, and can foster community between neighbors from many different backgrounds and occupations. However, studies remain uncertain about the capability of middle-class families to break down class barriers. Still, mixed-income housing in the LINK district could also make the downtown area more accessible to some low-income residents, who are currently cut off by I-195 and are dependent on the bus system to commute downtown.

At the moment, however, developers of the I-195 district don’t seem to be prioritizing the inclusion of low-income residents in the district. Instead, the push is to attract new, high-paying research and medical jobs and the educated, affluent people from outside of Providence who would come with those new openings. The state-run I-195 District Commission, which is in charge of overseeing the development of the LINK land, has a page on its website titled “Residences & Luxury Lofts in Providence,” which speaks to the type of clientele the commission is hoping to attract into the city. Local universities, including Brown, Johnson & Wales, Rhode Island College, and the University of Rhode Island have plans to expand into the district, and Wexford Science + Technology and CV Properties LLC recently announced plans to develop a life sciences complex on five of the available acres.

All of these developments have the potential to generate new jobs and tax revenue for the city, and they will contribute a great deal to the ongoing revitalization of Providence. But at the same time, they will only reinforce the separation between the two facets of Providence: expanding the educated, wealthy part of the city into the district while once again excluding the other half of the city’s population.

Luckily, the potential for an integrated neighborhood still remains — some of the parcels of former I-195 land remain unpurchased and open for development. City officials should seriously consider mixed-income housing, which could create neighborhoods that bring both sides of the city together. Only by prioritizing the active inclusion of low-income residents into the new district, whether through mixed-income housing or otherwise, can Providence truly link together its long-separated neighborhoods.

Map: Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service