The events of September 11th hold a massive and merited weight in the world’s collective consciousness. It was a date in which great violence was perpetrated against peaceful victims, and the hatred of a few individuals altered the fate of a whole nation. Many had predicted the impending danger of radical events, yet most were not prepared for what happened. The short moments of chaos that transpired that day shaped the political future of several countries, and led to an extended campaign of violence with repercussions that can still be felt today – four decades later.

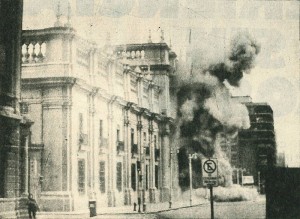

On the morning of September 11th, 1973, Chilean Armed Forces led by General Augusto Pinochet staged a coup against the democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende. The coup resulted in Allende’s suicide and a military takeover of government, a ban on political parties, and the imposition of a ruthless right-wing dictatorship that lasted 17 years. In this way, the first democratically elected Marxist government in the Americas was violently replaced by one of the many caudillo-led autocracies that were flourishing across the continent under U.S. auspices. As a key Cold War ally to the Americans, Pinochet made a point to brutally quash any leftist sympathies within Chile, and proved essential in doing the same across Latin America. His control over the state continued until he acquiesced to a majority vote in a 1989 plebiscite favoring a return to democracy.

Now, 40 years after the coup, Chile and the world commemorate the legacies that arose from this watershed moment in Latin American history. The most obvious is Pinochet’s dark history of human rights abuses and political repression, which gained notoriety worldwide shortly after his takeover.

While the coup was initially supported by wealthy Chileans and many others who were fed up with the hyperinflation and chronic shortages that marked the first three years of socialism, it made short work of the government’s system of checks and balances and destroyed what had proudly been considered “South America’s strongest democracy.” The dictator justified his harsh style by insisting that he had saved Chile from becoming a Communist state, but most Chileans do not believe this is true. A CERC poll this month found that only 18 percent of Chileans believe the coup stopped the imposition of Marxist totalitarianism. 63 percent of those polled believe the coup destroyed democracy instead.

Democracy was not the only thing Pinochet destroyed. According to NPR, the list of people killed, tortured or imprisoned for political reasons during his regime totaled 40,018. Government estimates place the number of executions at around 3,000. Of these 1,200 are desaparecidos, victims whose bodies have never been found.

Apart from the terrors he instigated in his own country, Pinochet and his intelligence agency (DINA, in its Spanish initials) were central players in Operation Condor – a transnational, US-backed plan to hunt down, weaken and destroy leftist groups and leaders in Latin American countries. Pinochet’s coup also helped open the floodgates for right-wing takeovers across the Southern Cone, with Argentinean, Paraguayan and Uruguayan military juntas cooperating with Chile’s new government and learning from its example.

While conservative groups may try to make the apparent success of Pinochet’s neo-liberal agenda the focus of his legacy, much of the rhetoric underpinning his economic “advances” has been brought into doubt. The “Chilean Miracle” that liberal economists raved about during the 1980’s has indeed produced a strong and open economy, but is also to blame for one of the worst inequality ratings in the developed world – and the worst of any OECD country. Those that trumpeted the successes of economic liberalization often forgot the human and social price that was paid – any opposition to entrenched economic interests was trampled and people under the poverty line were prohibited from demanding better living conditions.

The costly private university system created under Pinochet has also been a source of protest (especially in the last 3 years), and only fuels the educational and monetary divide between the upper and lower classes.

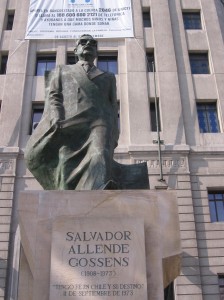

While the Chilean right wing may have won the battle in 1973, it is now obvious that Allende’s ideals were never truly defeated. The late president has been posthumously vindicated as a protector of democracy and a hero of the Latin American Left – something that might not have occurred had he lived through the coup. Admittedly, his government has been idealized to a certain extent, considering he oversaw a sizeable economic crisis, significant discontent over his administration’s policy of taking over private industries, and considerable polarization between the socialist executive branch and the more conservative legislature.

Now, however, young Chileans that grew up after Allende and Pinochet are calling for a more socially inclusive democracy, and see the late leftist president as a symbol for their new struggle.

Sen. Isabel Allende, the late president’s daughter and a best-selling author, says that “Forty years after, [Allende] is mentioned more than ever by the young people who flood the streets asking for free, quality education,” adding that “Allende’s profile keeps on growing while Pinochet is discredited.”

“This new generation is remembering that there are things that are far more important than the economy,” adds Patricio Fernandez, editor of Chilean magazine The Clinic. “It’s a return to the energy lived during Allende’s time.”

This energy may be instrumental for Chilean politics in the next couple of months. Polls indicate that most Chileans are unhappy with the current conservative government and will back previous incumbent Michelle Bachelet in this year’s presidential elections. Bachelet, a Socialist Party candidate whose military father was tortured and killed for his loyalty to Allende, has campaigned for wider public recognition of the dictatorship’s atrocities and plans to overhaul the Pinochet-era constitution.

In light of these current developments, President Allende’s last words before his suicide ring truer than ever: “I have faith in Chile and its destiny. Other men will overcome this grey and bitter moment.” It may have taken 40 years, but it seems that Chile has learned to value Allende’s lessons on equality and social inclusion–lessons that no one, not even Pinochet, could ever truly erase.