Two years ago, chaos broke loose when Syrian protesters began demonstrating their deep discontent with President Bashar al-Assad’s rule. As the next domino to fall in the Arab Spring, Syrians followed Tunisians, Libyans and Egyptians in voicing their outrage over human rights violations, economic stagnation and restricted political freedoms.

With such a backdrop framing our view of this country, the words “humor” and “Syria” might seem highly antithetical. For a country with a “Top 25” ranking in Foreign Policy magazine’s Failed State Index, it would seem nothing could be more serious than addressing Syria’s ongoing refugee crisis, economic decline or human rights violations. And from the perspective of the oppositional body, the Syrian National Council, there is nothing humorous about an international community reluctant to intervene, a 60,000-plus death toll and military checkpoints that frequently turn into deathtraps.

But this is not the story of military measures taken by rebel leaders to undermine al-Assad’s dictatorship. This is the story of how the Syrian people accomplished such a task, by developing a distinctive form of pitch-black humor borne out of the daily atrocities suffered under an authoritarian regime. If the question was how to construct an atmosphere that fostered comedy and humor in spite of the omnipresent rain of bomb shells, police harassment and a failing economy, the answer is relatively simple: comedy develops because of, not despite, these horrors. As poet and playwright Christopher Fry once wrote, “If the characters were not qualified for tragedy, there would be no comedy.”

In one oft-told story, a heavily armed Syrian soldier orders the driver of a rusted sedan to step out of his vehicle. The car and its driver, who is on his way from Aleppo to Damascus, have reached one of hundreds of military checkpoints controlling the flow of vehicles in and out of the Syrian capital. The driver readily presents his identification papers, making sure to mask any semblance of disapproval or defiance. “Now you!” the soldier orders, staring at the passenger. Breaking with the driver’s technique of offering the man anything and everything, the passenger shouts, “Oh, you’re screwed. Don’t you know who I am? I’m mukhabarat (military intelligence).” The soldier responds: “No, you’re the one who is screwed. This is a Free Syrian Army checkpoint!”

Some deconstruction provides valuable insight into why this story-based joke is so humorous and meaningful to the Syrian people. Firstly, mukhabarat, meaning “intelligence,” refers either to a clandestine intelligence officer or to the organization itself. The traveling mukhabarat assumes he has caught members of the Syrian Armed Forces harassing an officer of the state (himself)—an act which in a highly hierarchical and rigid authoritarian system can cost one dearly.

The retort and punch line that this checkpoint in fact belongs to the Free Syrian Army indicates that rebels, not the government’s military force, control the checkpoint. Since comedy is commentary, one implicit meaning of the joke is that the situation is so chaotic that even highly trained government spies can’t discern who the rebels are and who the Assad loyalists are. Whatever the interpretation, the great majority of Syrian citizens have been questioned or harassed by a government official at some point in their lifetimes.

This ultimately gets to the heart of why pitch-black comedy resonates so strongly with Syrian citizens. Rather than finding it exploitative or offensive, most Syrians can relate to it. Many in the United States are lucky enough to have daily problems that require simple solutions, most of which end up in stand-up comedy routines.

Dating and endless lines at women’s restrooms have been adopted into our collective consciousness as experiences that nearly everyone recognizes. In Syria the sounds of exploding shells, random security checkpoints, and food rations are the daily occurrences that become fodder for national humor. Another joke highlights the widespread dearth of basic goods and services, like the availability of gas: “A man returns home with a live chicken for dinner… His wife tells him the family no longer has a knife to slaughter the bird, nor do they have gas to cook it with. Upon hearing the news, the chicken begins clucking: ‘Long live Bashar! Long live Bashar!’”

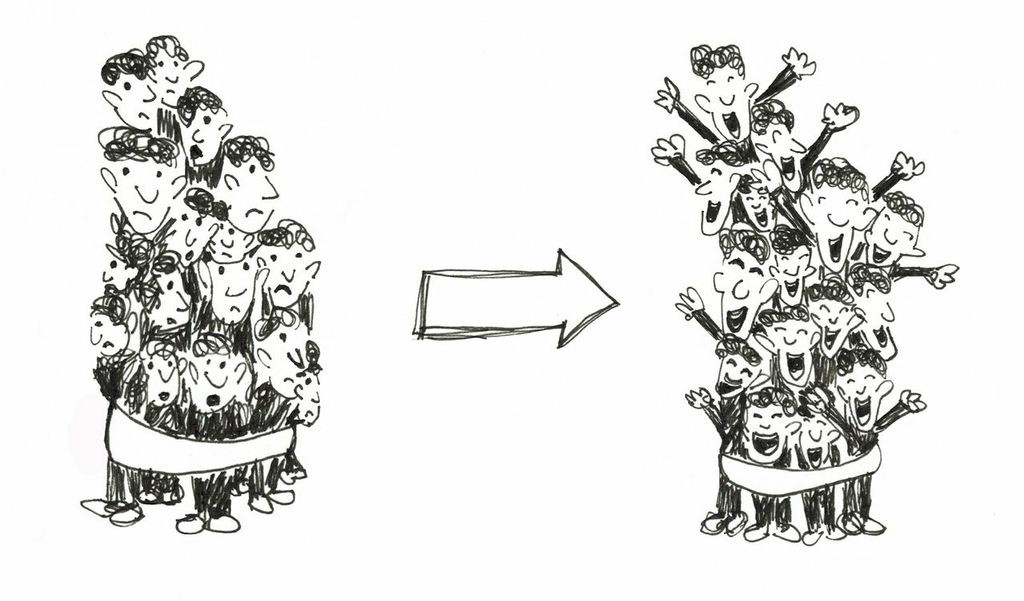

Comedy in Syria has served two valuable functions over the past two years. First, it has developed into a tool for political mobilization that has garnered support for opposition groups. Second, it has constructed a national coping mechanism that produces a modicum of joy in a landscape relatively devoid of it.

A host of comedy groups have arisen in opposition to the ruling Ba’ath Party’s leadership. One such group, Top Goon, produces a series of five-minute clips using dialogue, song, and finger puppets to depict President Assad and his cronies as mentally unstable and impotent. Reminiscent of the grotesque imagery often seen in beaked Venetian Carnival masks, Top Goon features an elongated and manic Assad dancing around while being plagued by demons. These darkly humorous images meet with lyrics that reinforce the opposition movement’s legitimacy: “Syria has called for it and the God of Heaven welcomed it…The days of patronage are gone, thanks to our peaceful revolution…Hey, Syria, our revolution is peaceful!”

Christa Salamandra, anthropology professor at Lehman College, calls Top Goon’s work “the kind of humor that you don’t necessarily laugh at…the ultimate red line for Syrian culture producers.” Salamandra neatly contextualizes Top Goon’s role by observing that while some culture producers toe that line by criticizing the regime “in very vague terms” only, dissident humorists such as Top Goon are “stomping over that red line.”

Another group, “The Germs,” is a comedy coalition whose name derives from Assad’s comparison of oppositional factions to the spread of germs and illness. However, their Facebook page, while an effective way of disseminating information, leaves them vulnerable to mukhabarat investigation because it boasts a tab devoted to “Top Fans”—individuals who are recognized for consistent interaction with the website. In August 2011, renowned Syrian political cartoonist Ali Ferzat was savagely beaten and his hands were broken in a moblike warning to cease producing comedic works that undermine the Assad regime’s authority. When people are being beaten and detained for producing controversial comedic material, how can an organized opposition group maintain a fan base?

Prior to the start of the Arab Spring, the Syrian mukhabarat failed to conceive of Internet and social media being used for revolutionary purposes. At first, protesters were able to take advantage of this, utilizing Twitter and Facebook to share information about how to combat the effects of tear gas using household items like Coca-Cola. By now, however, intelligence officials across the Arab world have developed systematic methods of shutting down servers and satirist organizations alike.

In order to circumvent government harassment, some more serious political organizations have scorned the Internet in favor of the printing press, rejecting the very medium that is often credited with giving such power and anonymity to the Arab Spring in the first place. Funded through individual private donations, opposition newspapers like Hurriyat (Freedom) and Enab Baladi (Grapes of My Country) are printed and distributed under the cover of night directly to people’s homes, largely in and around the capital, Damascus.

Thus far, satirists and comedians have struggled to maintain a presence via traditional print media: an above-ground satire newspaper, Al Domari (The Lamplighter) thrived for just two years in the early 2000s before being banned by the government. But if more comedy groups like “Top Goon” and “The Germs” followed the lead of the politically-minded Hurriyat, perhaps they too would be capable of reaching a large population without access to the Web. By distributing physical publications covertly to those who do not actively seek out satire, as one does on the Internet, they could likely expand their base. They would also provide an incredibly valuable service to those trapped in Syria’s major cities: a small degree of comfort-by-delivery.

We hear relatively little of the ways in which the Syrian people are fighting back through non-violence and creativity. Too often, the conflict is dichotomously depicted as the armed opposition shooting at the regime, and the regime shooting back. A third party has emerged, however, craving and deserving our attention. These writers, painters, sketch artists, broadcasters, filmmakers, printers and musicians have harnessed the simple human desire to smile, and with it they have activated a previously untapped faction: the majority of Syrians who prefer the pen to the sword.