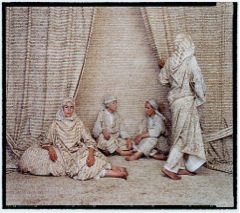

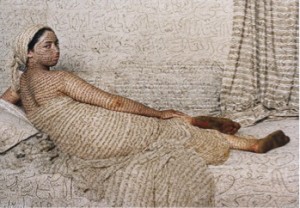

Lalla Essaydi’s photographic art depicting Arab women emerges from a simple yet powerful idea for the image: women, their clothing, their setting and an interaction. The photography series is a result of a project several months long. She chooses the location in which to stage the image, personally creates the garments that the subjects will wear, and finally, in a very meticulous process, she writes with henna on their faces, arms and feet. She then steps behind the camera and captures a visually stunning work of art. Her work often involves Islamic calligraphy and the medium of female bodies to address the complex reality of the lives of Arab women through their personal experience.

Lalla Essaydi’s work, including the series Les Femmes du Maroc, and Harem, Bullets, and Converging Territories, is heavily influenced by her identity as a Moroccan artist living in the West. Her photographs carry a very strong political message about the misrepresentation of Muslim women and their lives in the Orientalist paintings of the colonial era – the works that depict Middle Eastern and North African life. Essaydi makes it clear that these paintings do not assume a neutral stance in their presentation of the Muslim people, but rather reflect the dynamics of colonial politics. Paintings depicting Arab women speak more to the fantasies and imagination of the artists than any reality. Essaydi seeks to critique by counterbalancing the depictions of nude women in the “harem,” the mysterious space where women are not burdened with social norms.

Much of her work is in direct conversation with historical art. The series Les Femmes du Maroc (The Women of Morocco) is a response to French artist Eugène Delacroix’s Les Femmes d’Algere. The Women of Algeria). Delacroix visited Morocco in 1832 as part of a diplomatic mission – part of political processes that ended with France establishing a colony in Morocco that would last until 1956. Fascinated with the idea of a harem, he was finally allowed to see one in the neighboring Algeria. Although not fully nude or sexualized, the women seem lifeless and objectified. Essaydi’s critique depicts women with qualities that correspond to reality, altering their clothing and how they interact. Essaydi also explicitly responds to the depictions of women in Jean-Aguste-Dominique Ingres’ Grande Odalisque (1814) and Gustave Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot (1866). Odalisque by itself means a female slave or a concubine, and both paintings exude sexual narratives, depicting naked female bodies that reflect nothing but the author’s fantasies. Essaydi responds to these overtly sexual paintings by bringing back agency to the women, both in the way they are depicted and in the words they are carrying on their faces. The contrast of the parrot in Courbet’s painting with the white dove in Essaydi’s photograph also has a strong message – while former has strong exotic connotations the latter can be seen as women’s cry for peace in the Muslim countries in North Africa and the Middle East.

Essaydi’s work belongs in a larger body of contemporary art works that critiques Orientalists paintings. In the sense of that group, that includes Middle Eastern, North African, and Iranian artists, the blending of photography and calligraphy is not entirely new. However, Essaydi brings two new things to the table. For one, she inscribes the calligraphy onto the bodies of women therefore making the writings more personal. Second, the writings are not extracts from the Qur’an or classical literature, but all calligraphy writing represents the author’s own personal thoughts and feminist struggles, that are by extension those of her subjects. Lalla Essaydi has said that in her art she wishes “to present [herself] through multiple lenses — as artist, as Moroccan, as traditionalist, as Liberal, as Muslim. In short, [she] invite viewers to resist stereotypes”

Moving to the United States, Essaydi has noticed that the Orientalist work and the equivalent political and cultural processes from the time still dominate Western imagination of Muslim women. Therefore it is important to acknowledge the current use of gender and women in the political processes that cause and govern neocolonialism. Columbia scholar Lila Abu-Lughod has warned about using a very dangerous language of “saving Muslim women” to justify the war against terror and interventionism in Muslim countries. This language has been very prominent in mobilization for support in the United States led interventions and wars against terror in the Muslim countries, as evidenced by former first lady Laura Bush’s invoking the image of abused Muslim women. Abu-Lughod not only points this language inherently racists for its portrayal of Muslim societies as barbaric, but also claims what Lalla Essaydi’s work is all about – the need to view Muslim women within their own historical, social, and religious contexts.

Lalla Essaydi’s work not only critiques art and representation of Muslim women in the colonial era, but also triggers important questions that relate to contemporary politics related to gender and its role on interventionism and neocolonialism. These questions relate not only to representation, but also to stereotypes about gender, culture, religion, and sexuality, and the importance of these stereotypes in today’s relations between the West the Muslim countries. Analyzing these relations through the lens of gender illuminates a dangerous trend that has remained alive from the colonial era – the trend of taking away agency from Muslim women and using them to justify systems of oppression and injustices perpetrated by the West.