“Viva Arte Viva is a Biennale designed with the artists, by the artists, and for the artists,” proclaims Christine Macel, curator of the 57th edition of the Venice Art Biennale, a biannual international art festival. Invoking the words of Abraham Lincoln, Macel demonstrates a clear intent to politicize the well-known global art gathering. The overarching title of this cycle’s exhibition, “Vive Arte Viva,” prompts artists and the public to celebrate life in a political climate where humanism is jeopardized by a multiplicity of conflicts. In the spirit of a new communal embrace of life, Nigeria is being included in the contemporary exhibition for the first time ever. The inclusion of a Nigerian pavilion in a historically restricted art circle appears to address a legacy of elitist associations to and interpretations of culture. Nigerian art has been the target of colonialist interventions with misrepresentations and systematic looting. The inclusion of Nigerian art in the Biennale seems to point to progress towards recognition of Nigerian culture, but in fact it sheds light on the delay in integrating these marginalized voices in the one-sided ‘global’ art circle.

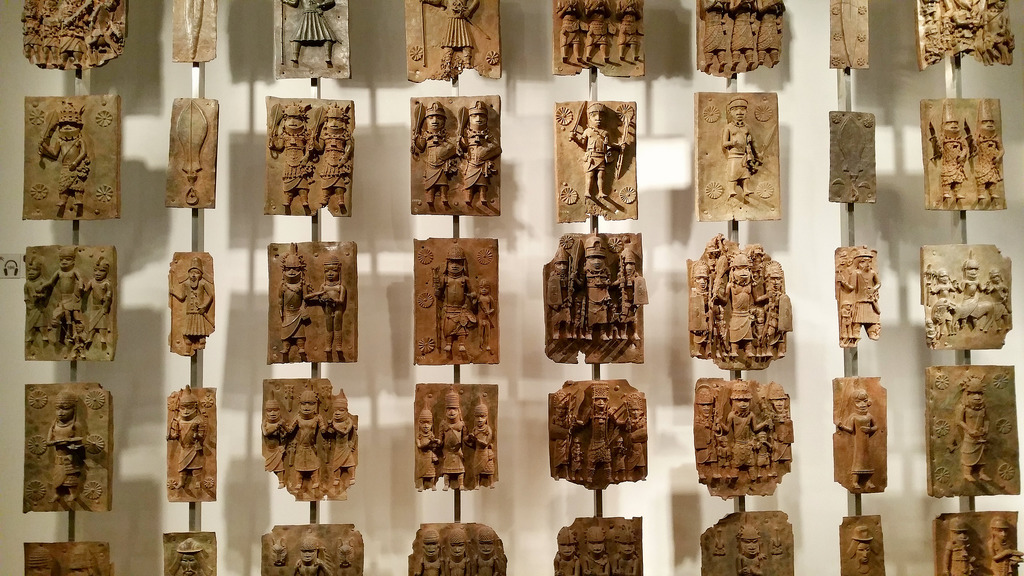

In February 1897, a punitive expedition looted almost 1,000 bronze artworks from Benin City in Nigeria, then a British colony. The history of these “Benin Bronzes” underlines both the prospect for global cultural collaboration and appropriation of indigenous cultures. Contact between Benin and European countries was established through trade in the 15th century and allowed the creation of Benin Bronzes. These artifacts, made through traditional, indigenous processes but with foreign raw materials, embody the expansion of commerce and the exchange of resources. Before 1897, these Beninese traditions were respected, although British indirect rule was already established. In 1897, when acting consul-general James Phillips was killed after interrupting a religious festival that prohibited the entry of foreigners, the British used the incident to escalate imperialist policies and violence. They consolidated British imperial control and engaged in the looting of Benin Bronzes, most of which were displaced to the British Museum. The psychological damage left by the intrusion was as high as the material loss. “Benin Bronzes” were part of the Beninese’ cultural heritage and thus shaped their national identity. The looting also resulted in a sort of internal contradiction: although it allowed other countries to appropriate and distort the material and symbolic culture of the Benin Bronzes, it was also the debut of the Nigerian art on the global market.

The inclusion of a Nigerian pavilion at the Biennale for the first time has to be read in relation to the colonial history of Nigerian art. Although the Biennale is an opportunity for Nigerian art’s representation in the international art scene, the decision to open this window was made by the same countries that looted the Benin Bronzes during the 19th century. The inclusion of a Nigerian Pavilion in the Biennale may not be so much an attempt to enfranchise traditionally oppressed peoples, as it is a demonstration of the continuity of the power held by rich Western countries in the art world and society in general.

Indeed, though the Biennale is supposed to be representative of art across the world, it is managed by previously colonialist countries with a French curator and an Italian director. Its ideological principles, too, demonstrate its deeply biased practices. The organization was founded on three ideological pillars, one of which concerns the participating countries. Given limited space, the curator has leeway to select some national pavilions, while others automatically come back every year. While the Biennale praises itself for highlighting new countries every year, President of the Biennale, Paolo Baratta, argues that the permanence of some countries is equally important. He says, this system is “precious in times of globalization, because it gives us the primary fabric of reference on which the always new, always varied, autonomous geographies of the artists can be observed and better highlighted.” The bias in the nature of the “fabric of reference” is not only ignored, but denied. Ironically, Baratta puts at the heart of this year’s International Exhibition the Biennale’s “primary work method – encounter and dialogue,” and “artists, whose worlds expand our perspective and the space of our existence.” Meanwhile, permanent countries include Germany, Belgium, France, and the United States. Although Nigeria has been invited after having competed for the last three editions without success, the decision does not mean that it will be included in future editions. Its pavilion is a temporary installation in a historic building. Permanent pavilions are only for countries that have ‘shaped’ the art world.

Until now, Nigeria has never been an official participant in the ‘International’ Exhibition but has contributed to all participations indirectly. Created in 1895, the Biennale was born in an art world very much influenced by the Benin Bronzes, which arrived at the same time in the Western markets and museums. Nigerian art informed the history and cultural perspective of the countries that have had permanent pavilions at the Biennale for over a hundred years, but this influence is only legitimized now. “How About NOW?,” the theme of the Nigerian 2017 Pavilion questions this unbalance. When asked for a statement, the exhibition’s curatorial team said they see the Nigerian pavilion as “a timeline. It arrives from the past, then, to take off to the future. Quite simply the time for Nigeria is now.” The Nigerian Pavilion’s exhibiting artists Peju Alatise, Victor Ehikhamenor, Qudus Onikeku, and Wana Udobang plan to present a multi-layered narrative. They ask questions of social and political status quo and tie local history to global narratives. Informed by the country’s past, they want to shape a future including both native communities and a global audience.

The content of the Nigerian Pavilion is known to Macel, the curator of this edition of the Biennale, who may in fact be a true proponent of the 57th edition’s theme “Viva Arte Viva” and its global and inclusive ambitions. She is the reason for Nigeria’s inclusion and likely wants to change the status quo of the art world. Indeed, art has been defined by and associated to both Western countries and masculinity. The curator’s mere presence is already questioning traditional associations and gendering of art.

Nonetheless, the inclusion of the Nigerian Pavilion does not repair the 1897 violation committed by the British. Although many Benin Bronzes have been returned to Nigeria, the UK still refuses the right of Nigeria to all of them. Today still, Prince Edun Akenzua, great grand-son of Oba Ovoramwen who ruled during the lootings of 1897, is in conflict with Cambridge University’s Jesus College to repatriate a Beninese bronze coquerel, Okukor, which stood in the college’s dining hall until student protests in 2016 led to its removal. Ogunbiyi, an HSPS undergraduate at Cambridge cited in a Varsity’s article, has argued for the repatriation of the statue to Nigeria: “The university is in a position, as an institution, to not only demonstrate that they recognise how extremely inappropriate it is to hold on to these stolen works, but also that they deem the continuous calls of the court of Benin and the Nigerian government, valid. [Repatriation] would also go some way to counter a wider Eurocentric narrative in which African voices in these spaces are very often considered inadequate and unworthy. Repatriation becomes more than just physical, but also very symbolic for the wider black community at Cambridge.” The sculpture is still in storage awaiting a decision by the school.

There are still many reforms to be made in the art world. The inclusion of the Nigerian Pavilion not only reminds us of the delay in integrating Nigerian art in art history narratives, but also of the on-going understatement of other African countries’ artistic heritage. The backlash of the progress made by the Biennale by including Nigeria would be to reduce these singular artistic cultures to one – Africa’s. As Nigerian artist Ola-Dele Kulu communicated through a neon installation in the first Nigerian Pavilion last summer at the Architecture Biennale, “Africa is not a country!”. Will the International Exhibition truly commit to its values of “encounter and dialogue” this summer? All eyes are turned towards “Viva Arte Viva.”