President Barack Obama’s community college proposal has been touted as a revolutionary step towards universal education — one that will restore the middle class and kick start the economy’s growth for years to come. The president’s initiative would use federal money to pay for two years of community college for any student who remains in good academic standing. At the same time, the proposal asks states to fund at least one quarter of the program and mandates that community colleges improve their quality. According to the White House, improvement in their education means that community colleges should “develop online courses,” “work with businesses” and, more vaguely, “teach basic skills” and “meet students’ needs.” The conditions of improvement may be the Obama administration’s attempt to keep this initiative from being perceived as a handout. As Obama has emphasized, there are “no free rides in America…This isn’t a blank check. It’s not a free lunch.” However, even if the structure of the bill is political, the administration is not wrong in emphasizing the need for improvement in community college education. Still, achieving the goal of universal education is much more difficult than the community college plan presumes.

In the current community college system, the odds are stacked against students: only 20 percent of community college enrollees finish the two-year program within three years and only 15 percent of students earn a bachelor’s degree after six years. Some might argue that these outcomes are caused by the high price of tuition, which prevents students from completing their education. But for most low-income students community college tuition is entirely covered by Pell Grants — so it’s not tuition that prevents them from graduating. Students drop out because of other costs, including the high prices of books, childcare, transportation and housing. Obama’s plan, which aims to make only tuition free, wouldn’t address these costs. Instead, it would primarily benefit higher-income students whose tuition isn’t already covered by the Pell Grant program.

Financial limitations are not the only burdens community college students face. The academic counseling programs at community colleges are under-developed, and students don’t receive the advising or career training that would help them graduate, transition to four-year institutions or get jobs. Unless these resources are strengthened, sending more students to community college won’t necessarily improve students’ prospects — it might only further exacerbate existing problems of overcrowded and underfunded advising programs.

Furthermore, even if attempts at improvement are made, there’s no clear way to assure the quality of a community college education. Jonathan Alter, a proponent of Obama’s plan, writes, “While many find community colleges are under-appreciated gateways to success, others just aren’t good enough to be further subsidized.” In theory, Obama’s new program pushes for higher accountability to ensure better quality, but the standards the government will use to determine which colleges should be held accountable and how so are unclear.

There are many potential metrics the government could use for accountability, including standardized testing, employment and graduation rates. Yet all possess significant flaws. Standardized testing, which has been used to measure success in lower education, can’t be applied to the highly specific courses found in institutions of higher learning. Vocational training, which is the initiative’s major goal, cannot be easily measured — the knowledge required to be an advanced manufacturer or an IT specialist, for example, is intricate and fluid and not easily standardized. Furthermore, strict measures of standardization would only exacerbate the existing divide between community colleges and four-year institutions, which wouldn’t have to change their testing methods.

Another possible metric for accountability is graduate employability. Yet if community colleges are measured by, and their funding dependent on, students’ abilities to get jobs after graduation, the schools will likely be led to cut “non-productive” programs, like English and liberal art courses. While this might be necessary to fit the major goal of the initiative — to supply a competent, vocationally trained workforce — the loss of liberal arts education is a serious blow to students. And, as with using standardized testing, if community colleges devote all their resources to vocational programs, the divide between community colleges and four-year institutions will continue to grow.

Using graduation rates is another option. However, simply having a higher graduation rate doesn’t mean that the college’s offerings have improved or that students are really learning. In fact, tying benefits to graduation rates might just encourage colleges to push students to graduate with incomplete educations. Whether outcomes are measured through standardized testing, employment statistics or graduation rates, it’s hard to imagine any accountability mechanism that wouldn’t turn community colleges into vocational factories that bear little resemblance to their private and public four-year counterparts.

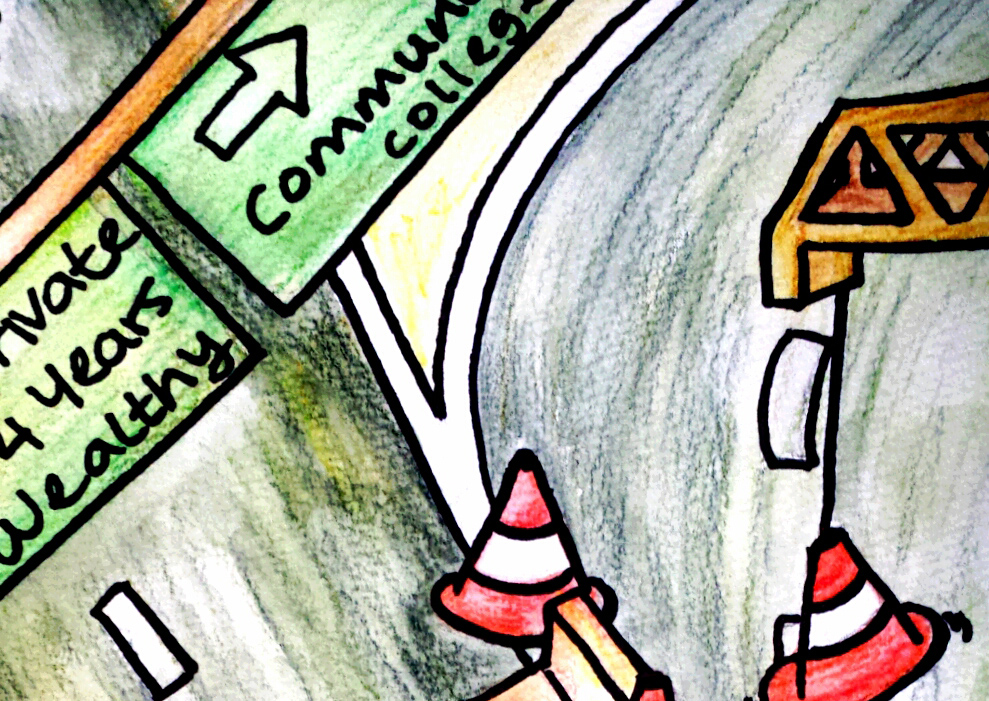

The initiative’s narrow focus on community colleges, by excluding lower-school education and higher education as a whole, is arbitrary and severely limiting. The GI Bill, which Obama argues is responsible for the United States’ international dominance and which motivated this initiative, allows recipients to use their funds at all accredited institutions, not just community colleges. To limit the program to community colleges strengthens the evidence that a different motive than simply universal education is at play. The plan attempts to overhaul community colleges to focus specifically on vocational and practical training — a focus that four-year institutions, for the most part, don’t emphasize — rather than holistic education. As such, Obama’s plan treats the education of lower-income students differently from that of higher-income students. By targeting community colleges and disincentivizing liberal education, the program creates a socioeconomic rift in educational opportunity.

Obama’s plan will also widen class divides by relegating the poor to limited community college programs rather than offering them funding to go to the institution of their choice. Many high-performing students from low-income families attend community college instead of pricey four-year institutions. This trend, known as “undermatching,” has a negative affect on high-achieving, low-income students. Studies that compare community college students with those at four-year institutions show that students with similar test scores and grades are far more likely to earn a degree at a four-year institution. Obama’s plan exacerbates the problem of undermatching by making it easier for students to attend community college but not helping them access a better four-year education.

It remains to be seen whether Obama’s plan is primarily politically motivated or just an ill-advised attempt to help low-income students get jobs. The former theory certainly makes sense, since a program funding higher education at all institutions — rather than just community colleges — would likely be considered elitist by a Republican Congress and would be unlikely to pass. Had Obama offered a bill sponsoring wide expansion of liberal arts education, it would have certainly failed to gain traction. This sentiment was best expressed by Republican Governor Rick Scott, who once responded to the funding of social science programs by remarking, “[i]s it a vital interest of the state to have more anthropologists? I don’t think so.” Furthermore, the initiative’s focus on tuition rather than the overall cost of community college — a focus that will primarily benefit higher-income students who don’t meet current grant requirements — means middle-income voters will line up to support the plan. With record high anxiety over the future of the middle class as well as an unprecedentedly obstructionist Republican Congress, tuition-free community college is a more reliable political bet, even if the bill doesn’t pass.

Yet, what Obama’s plan has in terms of political feasibility, it lacks in good policy. Even if the president’s proposal comes to fruition, in the face of existing class divides, income inequality and a poorly structured system of higher education, universal education will still fail to be truly universal.

Art by Julia Ladics.

This article is part of BPR’s special feature on higher education. Please click here to return to the rest of the feature.