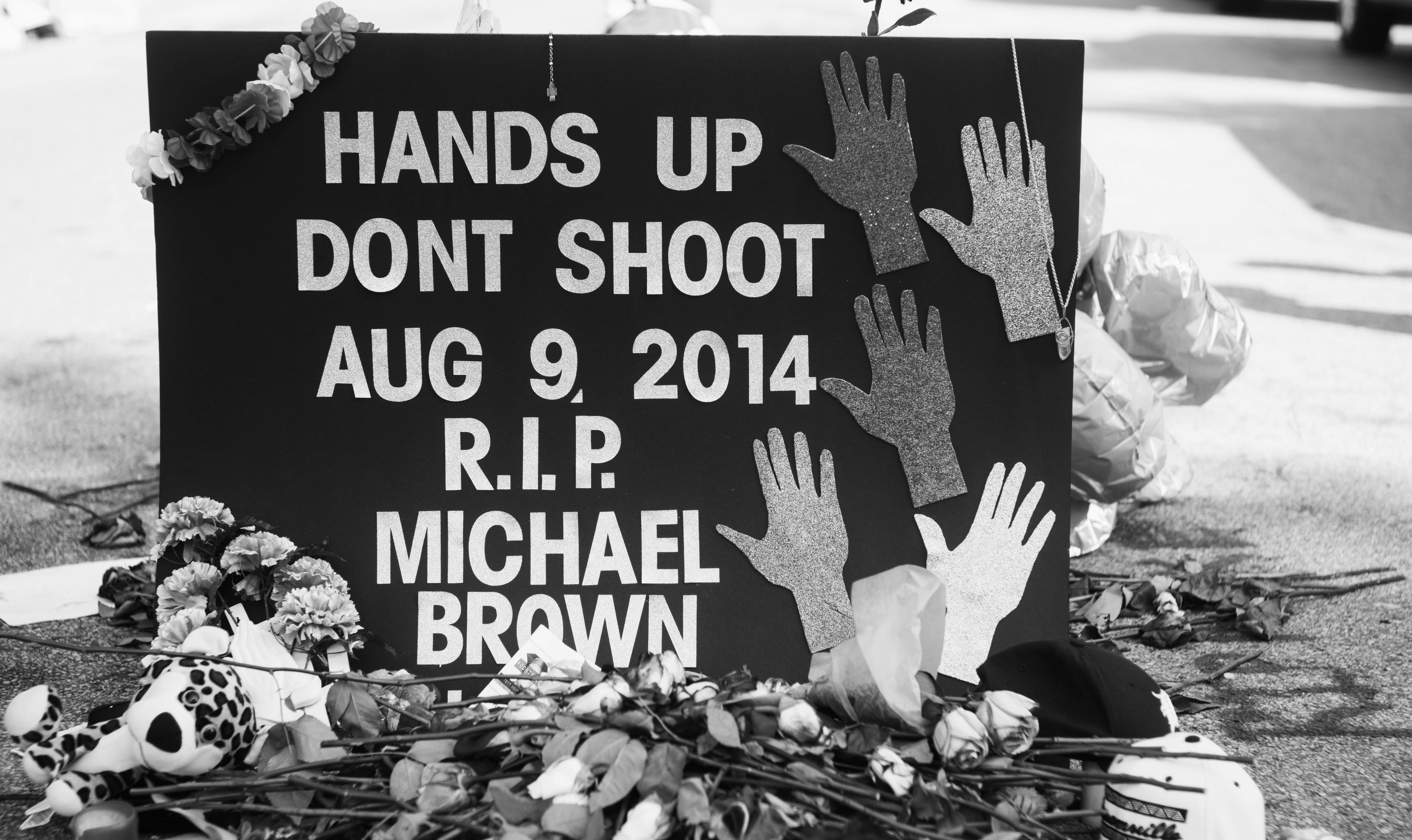

On Friday March 13th poet Kenneth Goldsmith performed a piece at Brown University entitled “Michael Brown’s Body.” A remixed recitation of Michael Brown’s Autopsy Examination Report, Goldsmith’s poem replaced the autopsy reports’ medical jargon with layman’s terms and altered its order. Despite these shallow modifications, the text retained it clinical shock, its detached description of entry and exit wounds, its voyeurism and its distasteful description of Brown’s genitals. An image of Michael Brown wearing a forest green cap and gown and holding a high school diploma was projected on the screen behind Goldsmith as he performed.

Many audience members and other performers felt profoundly uncomfortable following Goldsmith’s performance. Two scheduled presenters articulated reluctance to continue the program as planned, and many audience members were openly critical of Goldsmith. The criticism soon moved online as Goldsmith received outraged tweets and Facebook messages and online news sites published opinion pieces. Goldsmith even received a death threat on twitter. Most cited Goldsmiths aestheticizing of racial violence as the most disturbing part of the performance. Other’s pointed to his appropriation of a black body for his poetry—a reenactment and reiteration of historical appropriations of black bodies by white men. A vocal minority, confusing criticism with censorship, were outraged by the outrage and claimed critics were suppressing artistic freedom and free speech.

The Brown University event where this performance occurred, the Literary Arts department’s third Interrupt Conference, examined the intersections between digital culture, language and art. One thread of this examination was the role of authorship in the digital mediums. In the information age, the act of creation has lost its luster. Storify, Googling, “content aggregation,” the author today often organizes undigested mass, as opposed to bringing that mass into existence. The dissemination and resemination of the articles and listicles and gif essays is today’s norm. This is the cultural trend that Goldsmith is embracing with his poetry.

In Goldsmith’s initial response to the criticism he wrote on his Facebook page:

“…I did not editorialize; I simply read it without commentary or additional editorializing…. A writer need not write any new texts but rather reframe those that already exist in the world to greater effect than any subjective interpretation could lend. Perhaps people feel uncomfortable with my uncreative writing, but for me, this is the writing that is able to tell the truth in the strongest and clearest way possible…”

The phrase “uncreative writing” is central to understanding this response. Goldsmith belongs to a cluster of artists in the poetry community, who practice “uncreative writing” which embraces the digital age’s reinvention of the author. With the unprecedented amount of texts available to us in this age of Google search, this style focuses on refashioning preexisting texts instead of creating new ones.

This form of authorship, however, is complicated by its subsequent detachment of an author from their work. Conventionally the author of a text, the person who puts words to the page, is expected to take full ownership over those words. In the case of Goldsmith, he does not take responsibility for the words themselves (he didn’t write them), simply their form and presentation. Ultimately, however, “Michael Brown’s Body” represents a failure of that project. By moving into the realm of performance art, Goldsmith became very visibly a part of the text’s presentation. Goldsmith, a white man, stood on a stage and described a deceased and damaged black body. For members of the audience who watched this performance, his presence was inextricable from their experience of the text.

Goldsmith’s role as author became central to our understanding of the piece, as it should be.

“Michael Brown’s Body” is not the first instance of racial controversy in the literary art world that was rooted in the white identity of an author. There is a long history of racially appropriation in the art world. One similar incident, cited by artist Rin Johnson at the conference’s concluding penal, is the Donelle Woolford controversy. Last spring, the New York City Whitney Museum of American Art’s Biennial—a prestigious exhibition of younger and lesser-known contemporary artists—was steeped in controversy for its inclusion of Donelle Woolford. Donelle Woolford doesn’t exist. She is a fictional character, a black woman, conceived of by white male artist and Princeton professor Joe Scanlon and portrayed by three different black women that Scanlon hired. Many of the criticisms of Donelle were founded in a white man posing as a back woman (even if through “avatars”). The controversy reached a climax when a collective of black artists withdrew from the Biennial in protest.

Donelle Woolford, like “Michael Brown’s Body” is performance art. A distinction must be made though because unlike Goldsmith, Scanlon does not involve himself in the performance. He does not don “blackface” to portray Donelle Woolford. He does not stand on stage as a white man to present racially appropriative art, but hires others to do so. In a way, because of Scanlon’s visual—if not conceptual—absence from the performance he feels detached as an author, an alternative approach to Goldsmith’s detachment through “uncreative writing.” But what we find is, although Goldsmith’s literal presence in “Michael Brown’s Body” made his white male identity especially difficult to ignore, Scanlon’s authorial identity remains even if he isn’t physically present. Even if Scanlon’s art is meant to act as a commentary or a critique of racial appropriation, as a white man, he cannot be entirely absolved of his complicity in that appropriation.

Ultimately, the Whitney Incident can inform our understanding of “Michael Brown’s Body.” In matters of racial and political art, the identity of an author at times must be central to our understanding that art. It matters that Kenneth Goldsmith was a white man reading a description of a body that died at the hands of another white man. It matters that Goldsmith was taping into and using for his poetry the experiences of a person with entirely different cultural and economic experiences from his own. It matters that Kenneth Goldsmith was performing at an elite privileged institution in front of a mostly white audience who share in that privilege. As much as the separation of author and text may be useful as a critical tool in academic circles, in this case, who Kenneth Goldsmith is in relation to Michael Brown is necessarily central to our understanding of this piece of art. At times, believing that we can ignore the racial identity of an author can move into the realm of ignorance.