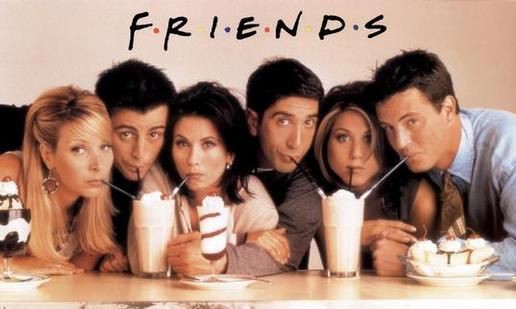

BuzzFeed brought some incredibly important journalism to the world this spring—they ran the numbers on how much money Joey owed Chandler on the hit sitcom Friends. Though the final tally of $114,260 is far-removed from reality, most things involving money in the show skewed towards the unbelievable. Although hypothetically depicting financially struggling New Yorkers, the show gave characters their dream jobs and dream apartments to go with it. But after endless episodes of carefree shenanigans, it became easy to wonder, Wait, do any of these people have jobs?

Though we may think of Friends as having the stereotypical sitcom makeup—ambiguously upper-middle class white friends—sitcoms weren’t always this way. The model set in the ‘60s and ‘70s by shows like The Andy Griffith Show and All In the Family set their focus squarely on middle- and working-class families. By the end of the ‘80s, Americans tired of increasingly clichéd family sitcoms, leading to a fracturing of the genre: more cynical visions of working class life, like Roseanne and The Simpsons, versus a new wave of shows that rejected family dynamics entirely.

The latter branch, exemplified by Seinfeld and Friends, chose to turn the lens from social issues to social dynamics, following gangs of friends rather than families going through after school special issues. Sitcoms became aspirational rather than representative in terms of class; characters were either never shown working or had fantasy jobs like actor and chef. Out were jokes about keeping the lights on and in were in-jokes about how characters’ apartments were unrealistically huge for middle class New Yorkers. By the turn of the century, financial comfort was the norm.

Where can we find the working class on the airwaves? Even shows that feature working class strains find their characters self-describing as middle class (The Middle); shows that claim to highlight the plight of lower income workers frame poverty as a temporary struggle and shift the focus to aspirations of making it, cheapening both consequences and jokes (2 Broke Girls). The most accurate depictions of working class Americans come on reality TV, in voyeuristic shows like Dirty Jobs, which through following “unsung laborers who make a living in some of the most unthinkable ways” evokes more schadenfreude than empathy.

The dearth of working class comedies may be a demand side issue. Americans have historically shied away from identifying as permanently lower class, excepting some proudly unionized blue collar professions. Horatio Alger’s “rags to riches” stories are considered synonymous with the American Dream for a reason. It’s easier to think of yourself as not-yet-rich than poor, which explains the appeal of shows where money isn’t an issue. Even those not hesitant to take on the label of working class likely don’t want to sit down to watch their struggles replicated on the small screen.

But there’s a difference between innocent escapism and erasure of reality. The shrinking of the middle class is well-documented, and though some of that comes from middle class spilling over into upper class, the percentage of households making under $35,000 a year actually slightly increased over the past decade. Though this change is much fretted over, American discussion of class still finds itself mired in 99 versus 1 percenter rhetoric. This loss of working class consciousness has allowed sitcoms about the economic realities of many Americans to fall out of favor. In some ways, we may be moving backwards.

Class is an often-ignored factor in television scholarship—the focus is more often placed on racial makeup. Sitcoms have a complicated relationship with race, often assuming “white as default” with either people of color as sidekicks or not represented at all. The lack of racial diversity on sitcoms is clearly visible, but class backgrounds are more difficult to distinguish, especially in sitcom fantasyland. Although representation is incredibly important along racial lines, representation in terms of class is often ignored in analysis.

But the few studies focusing on class are telling. Though working class characters are often portrayed as bumbling or relegated to side character status, working class viewers are still likely to identify with and find value in these characters. For example, they tended to perceive All In the Family’s bigoted, uneducated patriarch Archie Bunker as winning arguments over his college-educated son-in-law.

With this evidence, it’s possible that even potentially condescending and exploitative shows can be valuable for working class viewers. Bad representation may be better than no representation, but that doesn’t mean networks shouldn’t strive to accurately and respectfully portray a significant portion of America. It’s not enough to revive shows like Roseanne, which though proudly working class and feminist didn’t feature people of color or have much of a discussion of intersectionality.

There are some shows willing to take on these burdens, like the recent Asian-American-focused Fresh Off The Boat. But even these shows aren’t perfect, as proved by the tweets of Eddie Huang, whose memoir the show is based on: “[The show] got so far from the truth that I don’t recognize my own life.” He blasted the sitcom for being too lighthearted and not working with the pain of his original story. The very nature of sitcoms means that important problems risk either being smoothed over or becoming the butt of jokes.

Economic inequality may seem like a better target for dramas than comedies, but bringing back sitcoms with working class characters is still a worthy cause. Thinkpieces about class on TV have cropped up in the past few years, with outlets from the A.V. Club to The Atlantic weighing in on the shifting economic landscape of sitcoms. Still, it’s unclear if America needs—or wants—a return to the old guard of working class shows, which though potentially representative grew stale. It’s time for an honest, modern reimagining of class on TV.

Shows like New Girl could be potentially revolutionary in depicting the plight of millenials, who face a tough economic climate and the erosion of traditional career pathways. Instead, though there are jokes about losing jobs, there seem to be no real stakes for the characters, who live solid middle class lifestyles on part-time bartending and personal training salaries. It’s unnecessary to make sitcoms all doom-and-gloom, but compelling television comes from a real place. Give us the working class, millenials struggling to make ends meet, people working actual jobs and living within their means, families keeping it together. Ditch the huge apartment and kick Joey out.